Hi folks this is the first extract from MINSTREL BOY: THE METAMORPHOSES OF BOB DYLAN, the second volume of my ‘PICASSOF SONG ‘ trilogy. This covers the years 1967 to 1990.

The book will be officially released in early October – some pre release copies are available at ISIS online

MINSTREL BOY…. Extracts

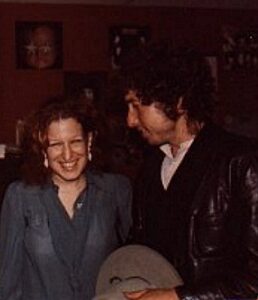

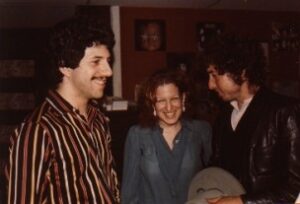

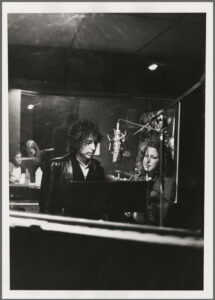

October 1975. Secret Sound Studios, New York. Bob Dylan is recording a duet with Bette Midler for her album Songs for the New Depression, a diverse if arguably rather ‘MOR’ collection, which includes a ‘disco’ version of Strangers in the Night, Tom Waits’ ‘pirate song’ Shiver Me Timbers and the romanticised travelogue Old Cape Cod, originally recorded by Patti Page in 1957. The song they are working on is Buckets of Rain, which somehow, during the recording session, has morphed into Nuggets of Rain.

During the session they work through the song several times, with the irrepressible Bette improvising an opening salvo of …Oooh… Sing to me baby!… making up her own lines between the verses in lieu of the lack of a chorus and even crying out …Bobby!… and …Hey there, Mr. B!… at the end. The sound is dominated by Ralph Shuckett’s organ and Moogy Klingman on piano, accompanied by prominent handclaps.

Meanwhile ‘Bobby’ has been making a few lyrical changes to fit in with Bette’s rather eccentric personality. The song is thus transformed from its origins as a wry, bluesy series of reflections into an upbeat and carefree number …Everything about you is bringing me misery… becomes …Everything about you is bringing me ecstasy… At one point, almost quoting ‘America’s answer to The Beatles’, he even sings …I like the way you monkey around…

The results are, to say the least, loose. Although much of the subtlety of the original has been rather smothered by the poppy arrangement, Dylan does not sound like he is too bothered. He is clearly enjoying himself. Later on a tape circulates of the whole session, in which it is obvious that the pair are flirting mischievously with each other. Bette asks him if he is a …one take man… but he reassures her that he can …last all night… As it turns out, though, they never get the chance to take any of this any further. It is strictly a ‘one night stand’.

Minstrel Boy

Both the lively You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go and the more intimate Buckets of Rain provide further contrast to the intense emotions displayed in many of the songs on Blood on the Tracks. These songs are rooted in the blues tradition of putting on a brave face when confronted with adversity. They wrestle with the complex nature of relationships, showing how lovers may experience several contradictory feelings at the same time. Both the versions on the album come from the New York sessions.

You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome follows the dark ruminations of Idiot Wind in the sequence of the album with a tone of breezy optimism. Its emotional message can be varied considerably depending on how it is handled. Slower versions have been recorded by a number of female vocalists, including Madeleine Peyroux, Mary Lou Lord, Miley Cyrus and Shawn Colvin, all of whom tend to emphasise the song’s melancholic qualities. Elvis Costello, on the other hand, tackles it at an even more frenetic pace than Dylan. While the more languid covers try to emphasise its prevailing tone of regret, in Dylan’s hands it comes over as a joyful celebration of the impermanence of a love affair. His tone is consistently playful and optimistic.

The song is addressed to a departing lover who the narrator accepts must leave, but the tone is never sad or melancholid. As in Lay Lady Lay and On a Night Like This it celebrates a passing affair which is not expected to become ‘serious’. In this case, however, the emotions are more complex, creating a distinctly bitter-sweet resonance, which is manifested in some understated but highly effective visual imagery.

The opening verse begins with a little personification: …I’ve seen love go by my door/ It’s never been that close before… ‘Close’, perhaps, but the ‘door’ has not been opened… Despite his protestations of affection, there is always a sense that the narrator is keeping the object of the song at a slight distance …Never been so easy or so slow… he sings, although this ‘slowness’ is certainly in contrast to the pace of the delivery. Then he confesses that …I’ve been shooting in the dark too long/ Something’s not right, it’s wrong… lines that convey a strong sense of regret, despite being sung so cheerfully.

We are then presented with the rather ambiguous image of …Dragon clouds so high above… These mythical creatures have often been seen in cloud formations. In the Western tradition, they tend to symbolise danger, although Chinese dragons are beneficial spirits. The narrator confesses that …I’ve only known careless love/ It always has hit me from below…

Minstrel Boy

There is some mild sexual innuendo here, suggesting that in the past he has been motivated primarily by lust, engaging in ‘careless’ (and thus temporary) love affairs. Careless Love is a well-known country song, which has been recorded by Johnny Cash, Leadbelly and many others. Dylan then delivers one of his trademark tongue-twisting apologies: …But this time round it’s so correct, right on target, so direct… As the title phrase is repeated we may, however, wonder why a love which is ‘so correct’ has to end.

The narrator then waxes lyrical about his lover: …Purple clover, Queen Anne’s lace/ Crimson hair across your face/ You could make me cry if you don’t know… Here he associates her with a range of colours. ‘Purple clover’ (more properly known as ‘purple shamrock’) is a plant that originates from the Brazilian rain forest. Queen Anne’s lace are delicate white flowers, which are contrasted with the lover’s crimson hair. He then retreats into his own thoughts, his memories perhaps clouded by this intense focus on her charms …Can’t remember what I was thinkin’ of… he confesses, absent mindedly. Then he becomes rather playfully flirtatious, telling her: …You might be spoilin’ me, too much love…

The way that the song segues into the first bridge provides a breathtaking evocation of the feeling of a new, refreshing and intoxicating love. Dylan’s use of pastoral imagery is reminiscent of the songs on New Morning, as well as Van Morrison’s exquisite ballad Crazy Love: …Flowers on the hillside bloomin’ crazy/ Crickets talking back and forth in rhyme… The remarkable phrase ‘bloomin’ crazy’ suggests an explosion – perhaps of purple clover and Queen Anne’s lace – across the natural vista, as if these flowers have instantly sprouted up.

The magical quality of the scene is reflected in the next line, as the crickets not only sing to each other but do so ‘in rhyme’. Nature, it seems, is alive and sentient. We then hear of a …Blue river running slow and lazy… In a line that recalls Time Passes Slowly’s evocation of a timeless reverie, the narrator declares …I could stay with you forever and never realise the time…

We are then quickly propelled back into the narrator’s own thoughts as he compares this affair with his past entanglements. He begins with the distinctly low key …Situations have ended sad, relationships have all been bad… but then surprises us with a rare direct reference to his poetic forebears: …Mine have been like Verlaine’s and Rimbaud… The tempestuous affair between the two symbolist poets ended with Verlaine shooting his teenage lover. The fact that Dylan has actually named his influences is, however, quite disarming. Then he tracks back a little, admitting that he has been getting rather carried away: …There’s no way I can compare/ All them scenes to this affair…

In the second bridge he continues to question his own motivations: …Yer gonna make me wonder what I’m doin’/ Stayin’ far behind without you/ Yer gonna make me wonder what I’m sayin’/ Yer gonna make me give myself a good talkin’ to… It seems that he accepts that the relationship cannot become more serious. He may even be relieved at the prospect of her imminent departure. We might speculate that he is letting her go for her own sake, rather than ‘destroying’ her, as Verlaine tried to do to Rimbaud. But whether he is acting out of self-interest or loving concern remains ambiguous.

As the narrator concedes that …Yer gonna have to leave me now, I know… he adopts a light-hearted, slightly self-mocking tone, claiming that he will look for her in …Honalula, San Francisco, Ashtabula… a string of seemingly random locations. Adapting ‘Honolulu’ to ‘Honolula’ is a blatantly comic forced rhyme, which perhaps makes us doubt his sincerity. Finally he declares that in her absence he will …see you in the sky above/ In the tall grass, in the ones I love… Perhaps he will see her face in those ‘dragon clouds’ – or even in heaven.

The reference to ‘tall grass’ echoes the lines in Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself, in which grass represents the vitality of life. The final statement suggests that he will somehow discern her qualities in others that are close to him. Perhaps the woman he is singing to is not an actual person but a representation of love itself – a chimerical figure like the Greek Goddess Aphrodite – who he will keep searching for, probably in vain.

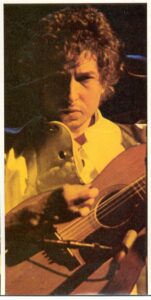

The ability to express such ambiguous and possibly contradictory sentiments is a feature of many blues songs. In Buckets of Rain Dylan follows an established blues model closely, using the distinctive Piedmont style finger picking guitar technique often associated with the gentle blues of Mississippi John Hurt. As a tribute to Hurt, Tom Paxton wrote the rather silly ‘sing along’ Bottle of Wine, from which Dylan’s melody is derived.

At first listen Buckets of Rain may appear to be a trifle, but despite it consisting of only five short verses with no choruses, refrains or bridge sections, it is a fitting conclusion to Blood on the Tracks. After the emotional turmoil depicted in most of the other songs it provides a soothing resolution to the song cycle. The narrator presents a calmly philosophical meditation on the vagaries of love and life. The song is lightly humorous and, unusually for a Dylan composition, eminently charming.

Dylan adopts a blues-style vernacular, delivering simple lines and images with great restraint and much irony. He presents us with a series of images which are counter-posed against the narrator’s feelings. The effect is, at times, quite magical …Buckets of rain, buckets of tears… it begins …Got all them buckets comin’ out of my ears/ Buckets of moonbeams in my hand… The ‘buckets’ metaphor is stretched to an absurd limit here, concluding with a twist on the romantic cliché of ‘moonbeams’. It seems at first as if the narrator may be overflowing with happiness. He reassures the girl that …I’ve got all the love, honey baby you can stand… The reference to ‘buckets of tears’, however, suggests otherwise.

The narrator then asserts his own steadfastness: …I been meek/ Hard like an oak… but then he tells us that …I seen pretty people disappear like smoke… He reassures her that he will not be one of those ‘friends’ who will ‘disappear’. Then he delivers a sensuous but respectful tribute: …Like your smile and your fingertips/ I like the way that you move your hips/ I like the cool way you look at me… In the most unexpected line, he declares …Everything about you is bringing me misery… This is the ‘misery’, perhaps, of the lover who is so obsessed that he cannot see beyond his own extreme emotions. Or perhaps it reveals that he has no chance of his love being reciprocated.

Undaunted, he delivers an enchanting little ‘nursery rhyme’: …Little red wagon, little red bike/ I ain’t no monkey but I know what I like… telling her that …I like the way you love me strong and slow… echoing the sentiments of You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome. But now he pledges not to abandon her …I’m taking you with me… he tells her …honey baby, when I go… although this seems like a promise he will be unlikely to fulfil.

The final lines are a quiet tour de force, condensing all the emotional turmoil of Blood on the Tracks into the delightfully tongue-twisting …Life is sad, life is a bust/ All you can do is do what you must/ You do what you must do/ And you do it well… followed by the pledge …I do it for you, honey baby, can’t you tell… Dylan’s utilisation of the blues format to express such a mixture of emotions is masterful. In these simple lines he also conveys a kind of serene, Zen-like detachment which ends the emotional roller coaster of the album on a note of both realism and hope.

His pronouncements also come over as a kind of whispered message to his listeners, playfully communicating the idea that we are all imperfect and subject to the unpredictable vagaries of life. Although life will inevitably confront us with tragedies, ending of course in our own deaths, all we can do is try to carry on, despite our imperfections. This is hardly an original idea but it is communicated with such joy and empathy that we, like the woman he is addressing, surely cannot fail to be captivated by it.

LINKS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply