BOB DYLAN’S I AND I: NO MAN SEES MY FACE AND LIVES..

…I is another… That’s obvious to me: I witness the unfolding of my own thought: I watch it, I hear it: I make a stroke with the bow: the symphony begins in the depths, or springs with a bound onto the stage…

–Arthur Rimbaud

How beautiful are your sandaled feet, princess!

The curves of your thighs are like jewelry,

the handiwork of a master.

2 Your navel is a rounded bowl;

it never lacks mixed wine.

Your waist is a mound of wheat

surrounded by lilies.

3 Your breasts are like two fawns,

twins of a gazelle.

The Song of Songs 7: 1-3

…And down here in the ghetto

And down here we suffer

But I and I a-hang on in there

And I and I, I naw leggo…

I AND I

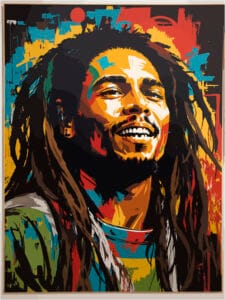

In the 1970s, Jamaica, an island of only two million mostly poor people, was the epicentre of a musical revolution which had a vast effect on the music and culture of the world. In the studios and streets of the capital, Kingston, in which there were almost no conventional music venues, a revolutionary approach to the use of rhythm was pioneered by producers and DJs such as Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, King Tubby, Joe Gibbs and Coxsone Dodd. The music was popularised by the brilliant poet-songwriter Bob Marley. Like most of the reggae stars of the time, Marley (who died tragically early at the age of only 36 in 1981) was a Rastafarian. He was dedicated to spreading the concepts and beliefs of this religion, which was deeply rooted in the Bible, but which transformed traditional Judeo-Christian perspectives into weapons of resistance against racism and the legacy of colonialism.

LEE ‘SCRATCH’ PERRY

I AND I IN REGGAE

Marley and other reggae singers also had the advantage of being able to use the exquisitely poetic language of Jamaican patois, a form of Creole English which is heavily influenced by the linguistic rhythms of the King James Bible and which found poetic expression in the works of poets like Louise Bennett-Coverley, James Berry and Linton Kwesi Johnson. Reggae music was a particularly strong influence on the punk and post punk movements of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s; although few white musicians were able to reproduce the uniquely distinctive rhythmic ‘feel’ of Jamaican music. Eric Clapton’s hit version of Marley’s startlingly militant I Shot the Sherriff is widely quoted, perhaps a little unfairly, as an example of a failed attempt to convey reggae’s uniquely subtle musical power.

BOB MARLEY

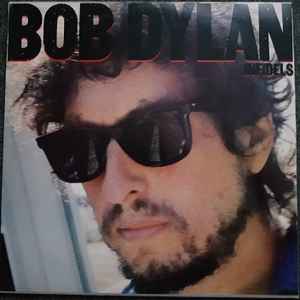

There is little doubt that Bob Dylan, like many other rock musicians, was influenced by reggae. The way he integrated three black female backing singers on the tours of 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981 (and later in 1986 and 1987) into his band was similar to the way Marley and his singers the I-Threes developed a dynamic call-and-response form of vocal presentation. The 1978 version of Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right which appears on the Live at the Budokan album, the jokey Biblical allegory Man Gave Names to All the Animals from 1979’s Slow Train Coming and Watered Down Love from 1981’s Shot of Love, however, are typical examples of ‘white reggae’, which unfortunately often comes over as a ‘watered down’ version of the original. Paul Simon had pointed the way with much greater success as early as 1972 by recording the highly moving Mother and Child Reunion with Jamaican musicians in Kingston itself. For the Infidels album in 1983 Dylan employed the powerhouse Jamaican rhythm section of bassist Robbie Shakespeare and drummer Sly Dunbar, who had provided the backing for countless singers in Jamaican studios. But although Infidels clearly displays such influences, it is not a reggae album. In fact its sound is dominated by the highly melodic guitar work of producer Mark Knopfler, leader of the ‘laid back’ blues based Dire Straits. But on I and I Dylan makes a definite attempt to engage with Jamaican music and Rastafarian beliefs. Rastafarians do not have a formal religious structure. Once, when asked if he attended church, Marley is supposed to have replied …I am a church… This open-ended attitude to spirituality seems to chime with Dylan’s post-conversion approach to his writing.

SLY AND ROBBIE

I AND I AND RELIGION

In a 1984 interview with Kurt Loader for Rolling Stone Dylan stated that …I’ve always thought there’s a superior power, that this is not the real world and that there’s a world to come. That no soul has ever died, every soul is alive, either in holiness or in flames… Later in the interview, however, he denies being a member of any specific church and refuses to condemn his friend Allen Ginsberg for his homosexuality. He also makes positive comments about other religions, such as Buddhism, which had influenced Ginsberg. It seems that at this point he retains a broadly ‘religious’ viewpoint without being tied to any particular creed. He appears to be searching for a new spiritual path which does not involve a complete rejection of his overtly ‘religious period’ but which fits in more closely with his world view as a symbolist poet. Yet his interest in religious texts of all kinds, and the Bible in particular, remains extremely strong. On Infidels he makes a clear break with the form of ‘born again’ Christianity which had dominated his albums and stage shows of 1979-81. Some of the songs are as complex and allusive as those on Street Legal and previous albums.

On I and I Dylan incorporates the title phrase into his own eclectic philosophy. Rastafarians use the expression to refer to oneself and God – who are identified as one and the same. Dylan adopts the phrase but modulates it in a number of ways. Despite the presence of Sly and Robbie, he does not really attempt to play authentic reggae here, although the rhythm section does provide a sinuous backing track, augmented by Knopfler’s fluid guitar lines and Alan Clark on keyboards, and a few rather limited echoey dub effects are added. In fact the take of the song on Infidels is quite restrained, especially in comparison to the full-on rock versions that he played in concert on around two hundred occasions between 1984 and 1999. The song has five verses and five identical choruses. It does not diverge from a rigid ABAB rhyme scheme and the lyrics were never altered in live performance. It uses a conventional twelve bar blues structure, although the rather languid tempo steps up considerably on the choruses.

The song has a clear and simple narrative, enhanced by a number of Biblical references. It is some time in the early hours. The narrator, who is spending the night with an unnamed woman (probably on a one night stand), wakes up and goes out for a walk, thinking deeply about the path his life has taken. Instead of returning to bed, however, he keeps on walking, still trying to focus his thoughts. The language of the opening verse is particularly moving and tender: …Been so long since a strange woman slept in my bed… he begins wistfully. Then he draws us in to the song, with …Look how sweet she sleeps, how free must be her dreams… He compares her to Naamah, the wife of King Solomon, one of the most revered figures in Judaism. His description also hints at some kind of belief in reincarnation …In another lifetime she must have owned the world… This is something of a gushing tribute. But now his imagination takes over …or been faithfully wed/ To some righteous king who wrote psalms beneath Moonlight streams…. Despite the obvious Biblical reference, the description also has considerable sexual overtones, as the psalm Song of Songs (sometimes called The Song of Solomon) is an explicitly erotic poem.

ANNAMAH AND SOLOMON

The chorus runs …I and I/ In creation where one’s nature neither honours nor forgives/ I and I/ One says to the other “No man sees my face and lives”… Already we have moved away from the gentle supplications of the first verse and into much scarier territory. While ‘I and I’, which is linked to a ‘creator’, still appears to retain the connotations of ‘myself and God’, it also takes the form of two specific figures, one of whom is speaking to the other. The narrator clearly wishes to achieve the kind of spiritual unity that singers like Marley celebrated. But the prospects of him achieving this state of contentment are limited. In the second line the narrator seems to be implying that this God is cold, unforgiving and dishonourable. In the fourth line the voice of the first ‘I’ is not the benevolent deity of Rastafarianism, many of whose followers celebrate with copious consumption of ganja, but the vengeful, warlike, patriarchal Jehovah of the Old Testament who terrifies his believers with statements such as … And he said, Thou canst not see my face: for there shall no man see me, and live…. (Exodus 33:20). Thus we sense that the narrator cannot sleep because he is tormented by his own uncertainties about the nature of existence. He is unsure whether God is a ‘loving father’ or a cruelly vindictive creator. While the Rastafarian notion of ‘I and I’ implies a kind of blissful unity with the divine, Dylan transforms into a vision of duality.

After this encounter with ’hellfire and brimstone’, the next pronouncements by the narrator are oddly prosaic and low key …Think I’ll go out and go for a walk… he mutters to himself …Not much happenin’ here, nothin’ ever does… He seems to have dropped the sentimental attitude to the woman in his bed, telling us that …if she wakes up now, she’ll just want me to talk/ I got nothin’ to say, ’specially about whatever was… He sounds mildly embarrassed, worried that he will not know what to say to her. The vague reference to ‘whatever was’ suggests that he certainly does not want to talk to her about love or the implications of their sexual encounter. So he begins his ‘walkabout’. We are given very few details about his location as he concentrates on his own inner thoughts and memories. He remembers that he once took an ‘untrodden path’ …where the swift don’t run the race… This is a reference to Ecclesiastes 9:11: … the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong… The next line …Took a stranger to teach me, to look into justice’s beautiful face… might lead us to expect that he is about to confess to some heinous sins and to testify to his redemption. We might also speculate that he is referring to the ‘beautiful face’ of the woman in his bed. But he seems to be concerned here not with love, but with an anthropomorphised version of justice, which is rarely described as ‘beautiful’. Justice, it seems, has taught him the callous Biblical credo of …an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth… quoted from Leviticus 24:20).

We can only speculate what form Justice’s, or perhaps Jehovah’s, revenge will take. The narrator continues his early morning journey, beginning with a crisp and evocative imagistic description of the loneliness he feels inside …Outside of two men on a train platform there’s nobody in sight/ They’re waiting for spring to come, smoking down the track… The choice of ’outside of’ here rather than ‘apart from’ in this very blues-influenced description is especially effective, further indicating the narrator’s increasing alienation from his surroundings. This is followed by a bizarrely offhand reference to the Apocalypse: …The world could come to an end tonight… he sighs wearily …but that’s all right/ She should still be there sleepin’ when I get back… Having absorbed various harsh Biblical strictures, he now appears to be cocking a snook at the ultimate Biblical prophecy of vengeance and doom. The light hearted and conversational way he expresses this reassures us that he does not really take such prophecies seriously. This is decidedly not a line which would have appeared in the songs of Slow Train Coming or Saved.

One of the compelling features of I and I is the way we follow the narrator’s inner thoughts as he swings through different emotions. With him having laughed in the face of the stifling religious dogma that has so oppressed him, we may expect a ‘happy ending’. But instead of returning to the ‘sleeping beauty’, at noon the narrator is still walking, still contemplating his fate. There is no indication that he will ever return. Some inner force which he cannot control is driving him away from the spiritual comfort that the ‘strange woman’ at home represents. He finds himself …pushin’ myself along the road/ The darkest part, into the narrow lanes… complaining that …I can’t stumble or stay put…

Dylan then delivers two devastating final lines …Someone else is speakin’ with my mouth, but I’m listening only to my heart…suggests that he is, or has been, under the mental control of others – those, perhaps, who have filled his mind with notions of cruel vengeance. But his heart – the seat of his deepest and most sincere emotions – is telling him that he can learn to speak for himself again. The final verse ends dramatically, with the mysterious statement: …I’ve made shoes for everyone, even you, while I still go barefoot… This appears to be a final declaration, not of vengeance but of humility. The imagery implies that he has made great sacrifices and considerable concessions to others to set himself on this winding path. He is unsure whether it will lead him to the unity between the human and the divine that the Rastafarian expression suggests or to a realisation of the essential separation of ‘God and man’. But as the song ends, and the road unwinds in front of him, this barefoot pilgrim is showing no sign of turning back.

Leave a Reply