BOB DYLAN’S DREAM: I WISH, I WISH, I WISH IN VAIN.

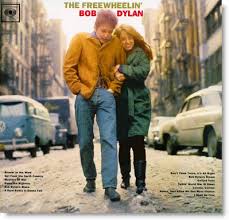

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan is one of the most important ‘breakthrough albums’ in musical history. One of the most impressive things about the collection is its variety of themes and moods, from the apocalyptic poetry of A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall to the playful silliness of I Shall Be Free. Amid the love songs, comic songs and protest anthems sits one of Dylan’s most beloved works, Bob Dylan’s Dream. This is a unique entry in his catalogue in that it deals exclusively with the issue of memory. Its message is also perfectly clear in a way that few Dylan songs are. It may be that the song represents his actual memories of his childhood or adolescence. However, at this time he was so steeped in folk music of various kinds that he had developed the ability to project himself into imagined situation.

LORD FRANKLIN

DYLAN’S DREAM

It is well known that Dylan based the song on the traditional ballad Lord Franklin (also known as Lady Frankin’s Lament) which tells the sad tale of the demise of the captain of a ship of exploration. The ship was lost Baffin Bay, Canada in 1855 in one of the many futile attempts to find the non-existent North West Passage. This is detailed in the sleeve notes to Freewheelin’, in which it is stated that Dylan learned the song from Martin Carthy – then a young folk singer yet to release his first album – on a trip to England.

The song has a very beautiful and striking melody, derived from the Irish air Cailín Óg a Stór. Bob Dylan’s Dream is a classic example of the ‘folk process’, by which melodies are interchangeable and many songs are developments of others. Although the subject matter of Lord Franklin is very different to that of Bob Dylan’s Dream, there is certainly some similarity in the emotions of wistful regret the songs convey. Whereas ballads like Blowin’ in the Wind and Hard Rain were more loosely based on their traditional antecedents, here (as with Girl from the North Country) Dylan uses the structure of the old song closely in his recreation, even mimicking the original lyrics in places.

The song was played by Dylan on a number of occasions in his early career but was then dropped until 1991, when (in a somewhat truncated version) it was featured in the acoustic sets of early Never Ending Tour gigs, often producing a particularly affectionate response from audiences. Its existence on such an early album illustrates that, even at this early stage, Dylan’s influences extended beyond the folk world. Despite being modelled on a traditional ballad, the Dream’s subject matter and emotional content link it more to the more sophisticated forms of mainstream popular music. In many ways, the song has more resemblance to the struggle with coming to terms with growing older implicit in songs recorded by Frank Sinatra, such as Young at Heart (1953, later covered by Dylan on Triplicate, 2017) and It Was a Very Good Year (1965), than most country, blues or folk material.

Bob Dylan’s Dream is not a song that requires interpretation. It spells out its message clearly. Although its narrator appears to be looking back on his own younger life, Dylan achieves far more than the nostalgic glow that surrounds the piece. He makes the experience a universal one, which can be relevant to anyone looking back on their youth. The story, about how the paths of youthful friendship will inevitably and sadly part, is told with great economy and lyricism. Its clear expression and upfront emotion made it a natural choice for smooth-voiced singers like Peter, Paul and Mary and Judy Collins, both of whom produce heartfelt if rather shallow readings. The way they change Dylan’s deliberately ungrammatical us of ‘was’ to ‘were’ is a good example of how Dylan’s work can be ‘watered down’. He has always used the timbre of his ‘ragged’ voice for positive effect in his songs. In this case the roughness of his singing, which is relatively conventional by his standards, offsets the lyricism of the song perfectly, preventing him diving into sentimentality or nostalgia. One outstanding cover version is that of Bryan Ferry (a singer capable of great nuance and subtlety) who has become one of Dylan’s leading interpreters. Ferry subtly varies his vocal delivery in order to bring out the song’s conflicting emotions.

The opening lines set the scene with great economy: …While riding on a train goin’ west/ I fell asleep for to take my rest / I dreamed a dream that made me sad/ Concerning myself and the first few friends I had… The first line is pure ‘Americana’. The narrator is now leaving his home and ‘heading west’ and the setting of the train echoes countless country and blues songs. Lord Franklin is also an account of a dream experienced by his lovelorn wife. But Bob Dylan’s Dream cannot really be called a ‘dream narrative’. It does not feature surreal occurrences or strange leaps of logic. If anything, this is a ‘lucid’ dream as the images we are presented with make the meaning absolutely clear. We are now projected back to a room that was once the meeting place of the narrator and his friends. Dylan conveys a feeling of great sadness in the line …With half-damp eyes I stared into the room… The narrator is almost crying. Already we get the sense that he is struggling to keep control of his emotions. The tension he sets up between nostalgia, present day realism and acceptance of the passage of time is a major element of the song – one which the ‘smoother’ singers tend to miss. We are told that he and his friends sat up all night in this rather dishevelled room, laughing and singing together and that they …weathered many a … (presumably metaphorical) …storm…

Dylan now begins to put emphasis on particular words, mainly on the third line of each verse in which the first and final lines tend to be drawn out, suggesting the trepidation that the narrator feels. In the third verse, which runs …By the old wooden stove where our hats was hung/ Our words was told, our songs was sung/ Where we longed for nothin’ and were satisfied/ Jokin’ and talkin’ about the world outside… he stretches out the word ‘where’, as if giving the listener time to focus on the scene that has been described. The use of ‘was’ here instead of ‘were’ positions the narrator and his friends as naïve, possibly uneducated youths. Dylan’s use of the vernacular – which he drew from the country and blues traditions – was a very important element of his persona in his early songs. Here it helps us to empathise with the narrator’s feelings. The memories he is experiencing may be idealised. But that is how, in real life, memories tend to be recalled.

The fourth verse begins with some very effective alliteration: …With hungry hearts through the heat and cold… suggesting that perhaps this life that is being looked back on was not necessarily so idyllic. The line that follows: …We never much thought we could get very old… is a crucial one, summing up exactly how so many people feel when they are young. Now the song turns from nostalgia to regret as the narrator admits that …We thought we could sit forever in fun/ But our chances really was a million to one…

The harmonica break that follows plays on the pathos of this line, with its faux-naïve ungrammatical expression. In the next verse, the naivety of the young is focused on, with the narrator commenting about how easy it was …to tell black from white/ It was all that easy to tell wrong from right… This is a sentiment Dylan would later expand on in his ‘renunciation of protest’ song My Back Pages. He now begins to focus on the tragic aspects of the scenario, telling us that the friends never dreamed that …the one road we travelled would ever shatter or split… Dylan captures the illusion that the young have that they will ‘live forever’ here with great eloquence.

The narrator laments the fact that years have gone by and he has never seen any of these friends again: …Many a road… he sings mournfully …taken by many a first friend… After another harmonica break, he finally pulls out the stops, becoming almost tearful …I wish, I wish, I wish in vain/ That we could sit simply in that room again… The three part repetition of ‘I wish’ is especially effective in emphasising these universal feelings, while the expression ‘sit simply’ conveys a strong sense of illusory innocence. The last couplet is especially memorable as Dylan cries …Ten thousand dollars at the drop of a hat/ I’d give it all gladly if our lives could be like that… Then the song stops almost instantly. These lines sum up with great eloquence the universal feelings older people often have towards their youth. They closely resemble the end of Lord Franklin: …Ten thousand pounds I would freely give/ To say on earth that my Franklin do live… It is remarkable how Bob Dylan’s Dream still embodies the older song, transposing a lament for a tragic event into a lament for lost youth; thus channelling the emotions of an old ballad that is a tragic lament into the universal tragedy of growing old. The fact that Dylan appeared to understand these feelings so well at the age of only 21 illustrates that already he had already developed the knack of imagining thoughts and emotions that had not necessarily yet really experienced himself.

Leave a Reply