My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head….

William Shakespeare, Sonnet 130

O my Luve is like a red, red rose

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve is like the melody

That’s sweetly played in tune…

Robert Burns A Red, Red Rose

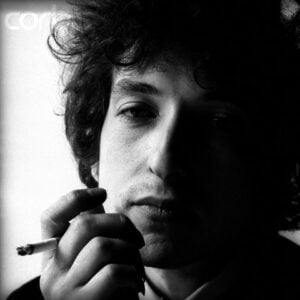

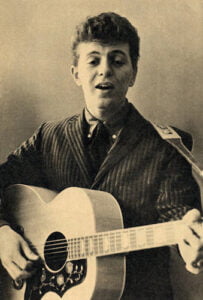

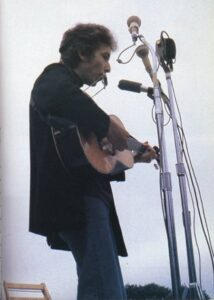

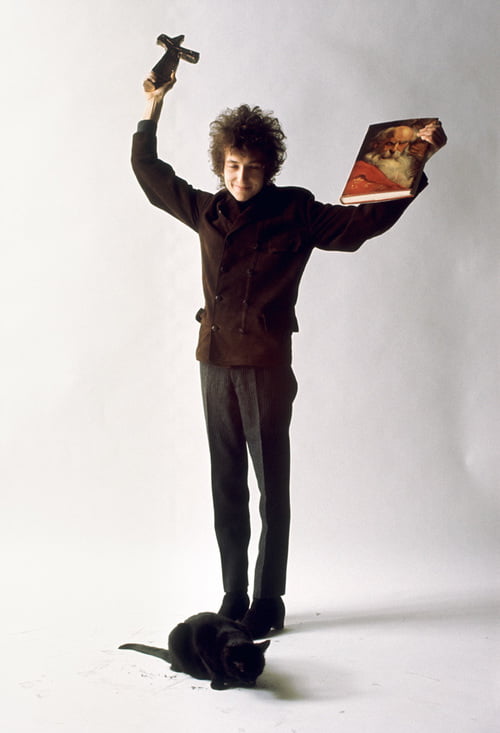

DYLAN’S LOVE SONGS

In the early 1960s, Bob Dylan was an extremely prolific writer, producing so much quality material that much of it would not fit on his albums. From a distance of several decades, it is sometimes necessary to remind ourselves that – despite the sophistication of the songs and their plethora of literary and musical references – Dylan was then still only in his early twenties. The evolution of his love songs from 1964 and 1965 reflects the longings, disappointments and emotional chaos that often characterise a period of life in which relationships start to become serious, yet may be subject to sudden and volatile change. While it is often a risky enterprise to relate particular songs to specific lovers (although fans are naturally tempted to do so) the historical facts of Dylan’s relationships with women in this part of his life are well known. In his early years in Greenwich Village he hooked up with the artist Suze Rotolo, who was just nineteen when she appeared on the iconic cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. She is said to have stimulated Dylan’s political awareness and encouraged him to compose the series of protest songs that made his name.

Within a year Dylan had become world famous. Fame, of course, often brings sexual temptation and like many young male stars of the period there is little doubt that he indulged in affairs and liaisons with a number of female entertainers and celebrities. Among the best known were Edie Sedgwick, a model who was a scion of Andy Warhol’s ‘Factory’ set up; Nico, the German chanteuse later to become involved with the Velvet Underground and Joan Baez, who was a similar age to Dylan but had been a prominent folk singer since the Age of eighteen. It is likely that these relationships ‘overlapped’ with each other before he secretly married model Sara Lownds in late 1965. The love songs that he composed during this period run the full gamut of emotion – from ecstatic avowals, confusion and uncertainty to extreme bitterness. They are sometimes comical, sometimes bleak and occasionally joyful. His earlier love songs had tended to be either pure expressions of devotion or nostalgia like Girl From the North, Tomorrow is a Long Time and Boots of Spanish Leather or philosophically detached observations on the end of relationships like Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright or One Too Many Mornings. But as he matured, the range of such songs rapidly became broader and their nature more complex.

LOVE SONGS AND POETRY

Dylan was reading voraciously at this time and his major literary influences – which included the Beat Poets, Whitman, Edgar Allan Poe, Rimbaud and Shakespeare – were being subsumed into his writing. Equally influential, however, were popular songs from a range of sources. Up to the 1960s, the love song was easily the most dominant lyrical construct in all forms of popular music. Mainstream ‘show tunes’, however, tended to be overly sentimental, often presenting an idealised view of love which would ‘last forever’. In the blues, the dominant mode was that of meditation on broken relationships. This was often a coded representation of the lives of suffering that many black people were enduring. Yet male blues singers in particular tended to counter this with sexual boasting.

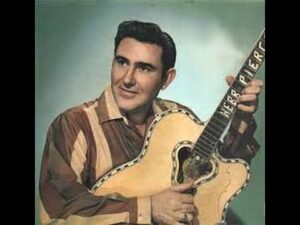

It was in country music – mainly the music of poor whites in the southern states – that the tradition of emotional realism in American song became most clearly established. Songs like Cold, Cold Heart and Your Cheatin’ Heart by Hank Williams, who Dylan (in his Poem for Joanie) called his ‘first hero’, were mostly focused on the emotional pain of heartbreak. Williams was deeply influenced by the blues but his songs conveyed this pain in a visceral way that included strongly self deprecating elements. He presented himself as vulnerable in a manner that ‘sophisticated’ singers like Frank Sinatra or Dean Martin could never convincingly convey. A song like I Fall to Pieces (written by Hank Cochran and Harlan Howard) allows Patsy Cline to ‘confess’ her own emotional instability with considerable emotional power. She Thinks I Still Care (written by Stephen Duffy and Dick Lipscomb) by George Jones depicts a lover whose attitude to his ‘ex’ is nothing less than callous. Just Can’t Live That Fast Any More (recorded by Lefty Frizell) and Webb Pierce’s There Stands the Glass catalogued the effects of alcohol and depression in destroying loving relationships.

WEBB PIERCE

Most of Dylan’s love songs of this period reflect such emotional realism, although he tends to disguise his true feelings with obfuscation and a poetic sensibility that renders the songs capable of multiple interpretations. Ballad in Plain D, from 1964’s Another Side album, however, is an exception. In this rather problematic work he describes an actual incident from his life in graphic detail and expresses his own pain and disgust at what happened in unequivocal terms. The song relates the story of Dylan’s confrontation with Carla Rotolo, Suze’s older sister, who strongly disapproved of her sibling’s romance with the scruffy young ‘beatnik’ singer. It has a strong melody, derived from the traditional Scottish air The False Bride, whose protagonist describes the pain he experiences when his lover marries another man. Dylan’s vocal performance is compelling and the recording includes an effective and poignant harmonica solo. It also has a number of evocative lines such as …shattered as a child to the shadows… …leaving all of love’s ashes behind me… and, most movingly ...I think of her often and hope whoever she’s met/ Will be fully aware of how precious she is… There is little doubt that the raw emotion Dylan expresses here is genuine. But in the song’s eight minutes and thirteen four line verses, there is scant musical variation and the tone is uniformly depressing.

Dylan expresses his feelings with considerable venom, but lines like: …For her parasite sister I had no respect… present a very one-sided account. Later he, rather viciously, describes …nailing her in the ruins of her pettiness… He has often been highly creative with his use of pararhyme but the first couplet: …I once loved a girl, her skin it was bronze/ With the innocence of a lamb she was gentle like a fawn … which is extremely patronising towards its subject, sets an awkward precedent. Later he characterises their relationship, rather bizarrely, as a ‘magnificent mantelpiece’. Other inelegant phrases include … silhouetted anger to manufactured peace…, …the timeless explosion of fantasy’s dream… the tombstones of damage.. and finally, the fake profundity of … I answered them most mysteriously/ Are birds free from the chains of the skyway?… The song also has a number of rather ‘forced’ phrases: …from her mother and sister, though close did they stay… …Beneath the bare light bulb the plaster did pound… …And she in between, the victim of sound… It is as if Dylan is striving to be ‘poetic’ in a rather contrived way, but that the emotion he feels has, for once, blinded him to lyrical discipline.

The most effective lines in the song are those in which the singer, with disarming honesty, admits that he is as much to blame for what happened as the ‘parasite sister’. …Myself, for what I did, I cannot be excused… he sings …The changes I was going through can’t even be used… He admits that …The words to say I’m sorry I haven’t found yet… Despite the song’s many flaws, and its uncharacteristic plunges into doggerel and spitefulness, it does have a quality of raw emotional honesty which echoes that of some of the more outspoken country singers. Dylan has never performed the song live. A few covers exist, including versions by Michael Chapman and Gordon Lightfoot. But Dylan himself confessed, in a 1985 interview with Bill Flanagan, that putting this highly uncharacteristic song out had actually been a mistake.

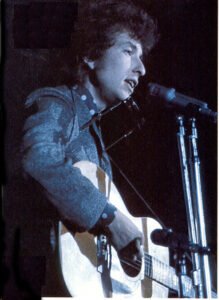

The Another Side album marked Dylan’s retreat from topical songs. By the time of its release, the landscape of American popular music had been completely changed by the unprecedented all-conquering success of The Beatles. Many of Dylan’s folk singer contemporaries regarded the British ‘beat group’ as purveyors of mindless commercialism but Dylan quite correctly recognised them as the avatars of the massive transformation of American rock music that was soon to come. His own move into playing with rock bands would be soon be another major factor in this huge cultural shift but on Another Side he was still working acoustically. Despite this, a number of the album’s songs seemed to anticipate the imminent move into rock. These songs approached the subject of love playfully, and even – in true rock and roll style – sexily. Spanish Harlem Incident is a distinctly lustful ode to a sensual ‘gypsy girl’ that the narrator encounters in a district of New York that had already been immortalised in Spanish Harlem (written by Jerry Leiber and Phil Spector and first recorded by Ben E. King in 1961), a memorable soul ballad with poetic lyrics which describe a beautiful woman as a lone ‘rose’ growing in the harsh environment of the ghetto. Dylan, however, goes straight for the jugular. His song, which has six verses and no chorus or refrain, boasts a rock-style rhythmic ‘pulse’ driven by a strongly ‘Latin’ guitar riff. It can be regarded as something of a ‘lost classic’ in Dylan’s oeuvre. There is only one known live performance, although there are a number of rock covers, including versions by The Byrds and Joan Osborne and an especially spirited take by Dion DiMucci.

DION DI MUCCI

From the outset the girl is described as decidedly ‘hot’: …Gypsy gal, the hands of Harlem…. Dylan begins …cannot hold you to its heat… He continues: …Your temperature’s too hot for taming/ Your flaming feet are burning up the street… He implores her to …take me/ Into the reach of your rattling drums… and declares, using barely disguised innuendo that …You got me swallowed… In another vivid phrase we hear that she has …pearly eyes so fast and slashing… and …flashing diamond teeth…. But this is not simply a tale of lust. It seems that the girl is a fortune teller, who the singer playfully demands to reveal his ‘fortune’ and his ‘lifelines’. Indeed, she appears to represent some kind of key to his future. The penultimate verse features Dylan musing …I’ve been wondering all about me, ever since I seen you there… We get the impression that he has not really formed any relationship or connection with the girl but has merely been inspired by her to create ‘sexier’ music. In the final triumphant verse, he declares …You have slayed me, you have made me… which is followed by the rather extraordinarily visceral …I got to laugh half ways off my heels… and then a final teasing (and slightly surreal) appeal to the girl: …I got to know babe, will you surround me… which is followed by the rather wonderful, if surprisingly introspective, concluding line …So I can know if I’m really real…

On Another Side, Dylan embraces the implicit sexuality of rock and roll, which The Beatles and The Rolling Stones were currently exploiting while performing in front of hordes of screaming fans. Soon the girls would be screaming at Dylan too. Rock and roll, especially transmitted through the figures of Elvis, Little Richard, Buddy Holly and Chuck Berry, had been his first musical love. In a hugely controversial move, he would enter the fray of the rock world in a very uncompromising manner. Rather than adding a few musicians to provide ‘tasteful’ accompaniment he would lead a band playing loud blues-based rock. In doing so he would permanently alter the nature of the rock medium itself, demonstrating that ‘electrified’ music could showcase complex lyrics. Spanish Harlem Incident is a kind of rehearsal for this coming move. The figure of the girl represents the sensuality and power that tends to be missing in the earnest genre of folk music. Dylan leaves us in no doubt that he is fascinated by and highly allured by the prospect of embracing the broader musical horizons that will soon follow.

The two songs which bookend the album, All I Really Want to Do and It Ain’t Me, Babe, double as personal statements about where Dylan stands in his career. On the album he delivers All I Really Want to Do in one take as a comic piece, with deliberately exaggerated sentiments and even a little judicious yodelling, echoing the style of country stars like Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams. The song is perhaps Dylan’s most playful address to a lover. Throughout the performance, he seems to be finding it hard to stop laughing. The song was performed frequently in 1964 and 1965, often as the final encore. It was revived in 1978 in a full band arrangement with flute and saxophone. After that it was largely retired from live performances, although there have been many cover versions of what appears to be, at least on the surface, an appealing and witty pop number. Cher had a hit with the song at the same time as The Byrds and it was later recorded by The Hollies, The McCoys, Peggy Lee, Bryan Ferry and many others; the majority of whom treat it as a conventional love song.

CHER, 1965

The song has six verses, all of which end in the tongue-in-cheek refrain … All I really wanna do/ Is baby be friends with you… The word ‘friends’ is frequently given ironic emphasis. Most of the other lines rely on repetition, mainly of ‘you’. The piling on of repetition, with the emphasis on the narrator pleading with the object of the song, has a comic effect. This is enhanced by the frequent use of internal rhyme. The song begins: …I ain’t lookin’ to compete with you/ Beat or cheat or mistreat you/ Simplify you, classify you/ Deny, defy or crucify you…. We may at first assume that this is directed at a potential lover who is sensitive to misogynist treatment. Perhaps it is a clever ruse by the narrator in ‘chatting up’ a woman. But the emphasis on the internal rhymes ‘beat/cheat’; ‘simplify/classify’ and ‘deny/defy’ sounds, in Dylan’s delivery, as if he is playing a game with the lover, presenting himself as rather charmingly assertive while still respecting her dignity and independence.

The rest of the song follows a similar pattern. The narrator declares that he does not want to ‘frighten/tighten you’, ‘shock/knock/lock you up’, or ‘drag you down/chain you down/bring you down’. Later he denies wanting to ‘analyze, categorize, finalize or advertise’ her, to ‘disgrace you, displace you, define you, confine you’, or to ‘select you, dissect you, inspect you’, ‘reject you’. In the final verses the pattern changes slightly as he states …I don’t want to meet your kin, make you spin or do you in… Finally he avows that …I ain’t lookin’ for you to feel like me, see like me or be like me… It is a memorable comic turn, with the aggressive harmonica playing between the verses emphasising the mock-pleading tone. On second listen, perhaps, fans may theorise that the song is actually directed towards them. This effect is achieved by Dylan refusing to give us any specifics of the relationship. We never find out whether this is a romantic relationship or not, although the hit version by The Byrds, which is graced by the sublime three part harmonies of Roger McGuinn, David Crosby and Gene Clark, presents the song as more straightforward declaration of love.

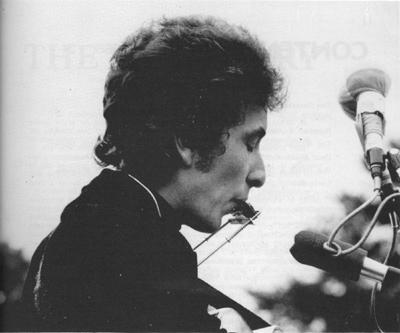

Some fans, however, suspected that Dylan was using the song to tell his listeners that he was not happy in the role of a prophet, a sage or the leader of any kind of movement. At the Newport Folk Festival on 24th July 1964 (where he performed an early version of the song) folk singer Ronnie Weaver had introduced him with the words …And here he is….Take him, you know him, he’s yours…. In Chronicles Vol. One Dylan reflects with horror on this statement, which he takes as an indication that he was now regarded as ‘public property’. Many of those in the ‘folk movement’ looked on him as a political spokesperson. This was a role that, especially in the wake of the assassination of Kennedy, he was already feeling distinctly uneasy with.

Like All I Really Want to Do, It Ain’t Me Babe is a song in which the narrator makes a series of denials to an unknown woman. The language is simple and direct, with little metaphorical content. Strongly worded repetition is again used to get the point over. The first two verses build into long choruses, with the third verse reiterating the message in a shorter form. The narrator accumulates reasons as to why he cannot live up to his lover’s expectations. The tone is rather similar to Hank Williams’ Cold, Cold Heart except for the fact that it is Dylan’s narrator, rather than his love object, who is being ‘cold’. The first line …Go away from my window… is the opening line of a song by the rather eccentric ‘operatic folk singer’ John Jacob Niles, which also has a slightly similar melody. At first the narrator takes a relatively gentle approach, instructing the would-be lover to …leave at your own chosen speed… He then begins to explain why he is giving her the ‘brush off’: …I’m not the one you want, babe/ I’m not the one you need… Then the build up to the chorus begins: …You say you’re looking for someone, never weak but always strong/ To protect you and defend you, whether you are right or wrong/ Someone to open each and every door… There is little ambiguity in the message. The narrator rejects his lover putting him on a pedestal and characterising him as a protector or saviour who will support her and love her unconditionally.

The disillusionment is completed by the emphatic chorus …But it ain’t me, babe/ No, no, no – it ain’t me babe/ It ain’t me you’re looking for babe… The repetition of ‘no, no, no’ has often been seen as a riposte to The Beatles famous refrain of ‘yeah, yeah, yeah’ in their massive worldwide hit She Loves You (1963). But if ‘yeah, yeah, yeah’ suggested an unbridled positivity and optimism, ‘no, no, no’ clearly signifies the opposite. In It Ain’t Me, Babe Dylan writes what can be considered one of his first ‘pop songs’, while turning conventional sentiments upside down. The song was soon recorded by mainstream acts like folk-rock band The Turtles, clean cut surf-rock duo Jan and Dean, pop-rock diva Nancy Sinatra and country legend Johnny Cash. Cash’s version is especially distinctive, as the song is a perfect vehicle for his powerful vocals, which reveal distinctive hints of vulnerability beneath his usual driving beat.

Perhaps the most affecting verse is the second, in which the narrator implores the lover, at first rather gently, to …Go lightly from the ledge, babe/ Go lightly on the ground… This is contrasted with the unequivocal …I’m not the one you want babe/ I’ll only let you down… He confronts her directly, attempting to destroy her illusions about him: You say you’re lookin’ for someone/ Who’ll promise never to part/ Someone to close his eyes to you/ Someone to close his heart… There is then a suggestion of possible tragedy: … Someone who will die for you and more… The narrator clearly indicates that he is not prepared to ‘martyr’ himself for her. The final verse more or less reiterates the message, with the narrator denying that he is prepared to …gather flowers constantly and come every time you call… Dylan uses the tropes of romantic songs to deliver a distinctly anti-romantic message. Yet there is a wistful quality here which suggests that it is possible that the narrator may actually be in love with the girl. Perhaps he is deliberately playing ‘hard to get’ by coming across as ultra-modest.

It Ain’t Me, Babe is one of Dylan’s most well known songs. Covers have appeared by Bryan Ferry, the Fleet Foxes, Sandy Denny, Joan Baez, Linda Gail Lewis, Barb Jungr, Lucy Kaplansky and many others. It became one of his first ‘acoustic songs’ to be rearranged for performance with a rock band in his ‘electric’ shows of 1965. It has since been performed by Dylan many hundreds of times. The song can be presented as a cruel rejection or a self-deprecating confession. One of the most moving performances occurs during the acoustic set in Dylan’s performance at the Isle of Wight Festival in 1969. Utilising his then-current ‘Nashville Skyline’ voice, Dylan delivers a gentle and sympathetic reading that is full of great tenderness. This is particularly evocative as the entire Isle of Wight show is presented as a quite deliberate deconstruction of the mythology surrounding Dylan himself. Although the song is a message to a lover, it has often been read – like All I Really Want to Do – as an unequivocal rejection of the political status which had been foisted on him.

I Don’t Believe You is another song from the album which hints strongly at Dylan’s imminent transition to rock. The narrator complains throughout about a girl who he has just spent a night of passion with, yet who treats him with disdain the next day. Dylan delivers the song with great wit and comic timing, moving seamlessly through bewilderment, disillusionment and finally defiance, all expressed with acerbic wit. The self mocking tone in some ways resembles Hank Williams’ Nobody’s Lonesome for Me, in which the singer bemoans the lack of sympathy he gets when his lover rejects him. But Dylan’s song is more graphic in its description of the relationship and less self-pitying. In terms of musical structure and lyrical attitude it has some resemblance to the blues standard Worried Life Blues (especially Chuck Berry’s version, from which it appears to borrow a guitar riff) later revamped by Dylan on 2006’s Modern Times as Someday Baby.

In I Don’t Believe You, the narrator seems to demand explanation, rather than revenge …I can’t understand… the song begins …She let go of my hand/ And left me here facing the wall…He complains that now he …can’t get close to her at all… His description of the night before is particularly evocative: …We kissed through the wild blazing night time… It seems that, in the throes of passion, she promised never to forget him. But now that the morning has come, she has blanked him …It’s like I ain’t here… he complains bitterly …She acts like we never have met… The last phrase, with some variation, is the song’s repeated refrain and its subtitle. The title itself never appears in the song. Dylan’s narrator plays the part of the wounded lover, who has supposedly been rejected for no reason. But his po-faced declarations of innocence are so pronounced that we are left wondering as to the veracity of his allegations. The narrator continues to assert his supposed lack of guile: …It’s all new to me, like some mystery… he protests …It could even be like a myth/ But it’s hard to think on that she’s the same one/ That last night I was with… For a moment he becomes rather wistful, declaring that …From darkness dreams are deserted… Again the playful alliteration suggests that he cannot really be as upset as he claims he is. Then he questions himself: …Am I still dreaming yet?… trying, perhaps, to convince himself that he has imagined all this. In a clever turn of phrase, he asserts that …I wish she’d unlock her voice once and talk… But such hopes are inevitably in vain.

By now, it seems quite apparent that the narrator has been exploited by a girl who has shown him little respect. But he still pretends not to understand this, asking the rhetorical question, again punctuated by playful internal rhymes: …It she ain’t feeling well then why don’t she tell/ ‘Stead of turning her back to my face… Later he protests that: …If I was with her too long or have done something wrong/ I’d wish she tell me what it is, I’ll run and hide… These rather half-hearted complaints are followed by more colourful descriptions of their sexual coupling. We hear that …her skirt, it swayed as a guitar played… and that, with comical double overemphasis …Her mouth was watery and wet… Later we get more intimate suggestions: …Though the night ran swirling and whirling/ I remember her whispering yet… As we ‘cut’ between his complaints and his fond erotic memories, we get a distinct impression that the narrator is actually more ‘miffed’ than upset. There is no suggestion of ‘true love’ here. As with Spanish Harlem Incident, the focus is very much on lust.

Finally he declares, as in Don’t Think Twice or One Too Many Mornings, that he will be leaving soon. He then gives the song an ingenious twist by asking the girl whether he should imitate her: …If you want me too, I could be just like you/ And pretend that we never have touched… He delivers a highly sarcastic denouement: …if anybody asks me “Is it easy to forget?”/ I’ll say, “It’s easily done, you just pick anyone/ And pretend that you never have met!”… It is thus hard to really sympathise with the protagonist. In the end he realises he has been toyed with, but boasts that this is an ‘easy trick’ that he himself could pull off. Given the somewhat whiney attitude he has displayed in the song, this is rather unconvincing. Whether or not we believe him, I Don’t Believe You takes the concept of a ‘love song’ into what, at least at the time, was largely unexplored territory. This is a song which – in the manner of contemporary songs like The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night and The Kinks’ You Really Got Me – is quite explicitly about sex. The song can also be seen as a kind of declaration of independence on Dylan’s part from the conventions of the kinds of love songs that were deemed ‘acceptable’ in the folk community.

I Don’t Believe You has been a constant presence in Dylan’s set lists throughout his career. It has also been covered by many artists. There is a particularly effective version by Al Stewart, whose dryly ironic delivery suits the song to a tee. On the turbulent 1966 tour, it was the second number in Dylan’s standardised ‘electric’ set that also included pumped up takes on Baby Let Me Follow You Down and One Too Many Mornings. At the epochal Manchester Free Trade Hall show in May 1966 (released as Live 66 in The Bootleg Series), with audible barracking been thrown at him, his drawling, defiant introduction to the song runs: …This is called “I Don’t Believe You”. It used to go like this…Now it goes like THIS!… before launching into an energetic and extremely powerful full on rock version of the song. Later, after the famous (and now extremely iconic) cry of Judas! , the phrase Dylan comes out with before his incendiary version of Like a Rolling Stone is …’’I don’t believe you!”

Leave a Reply