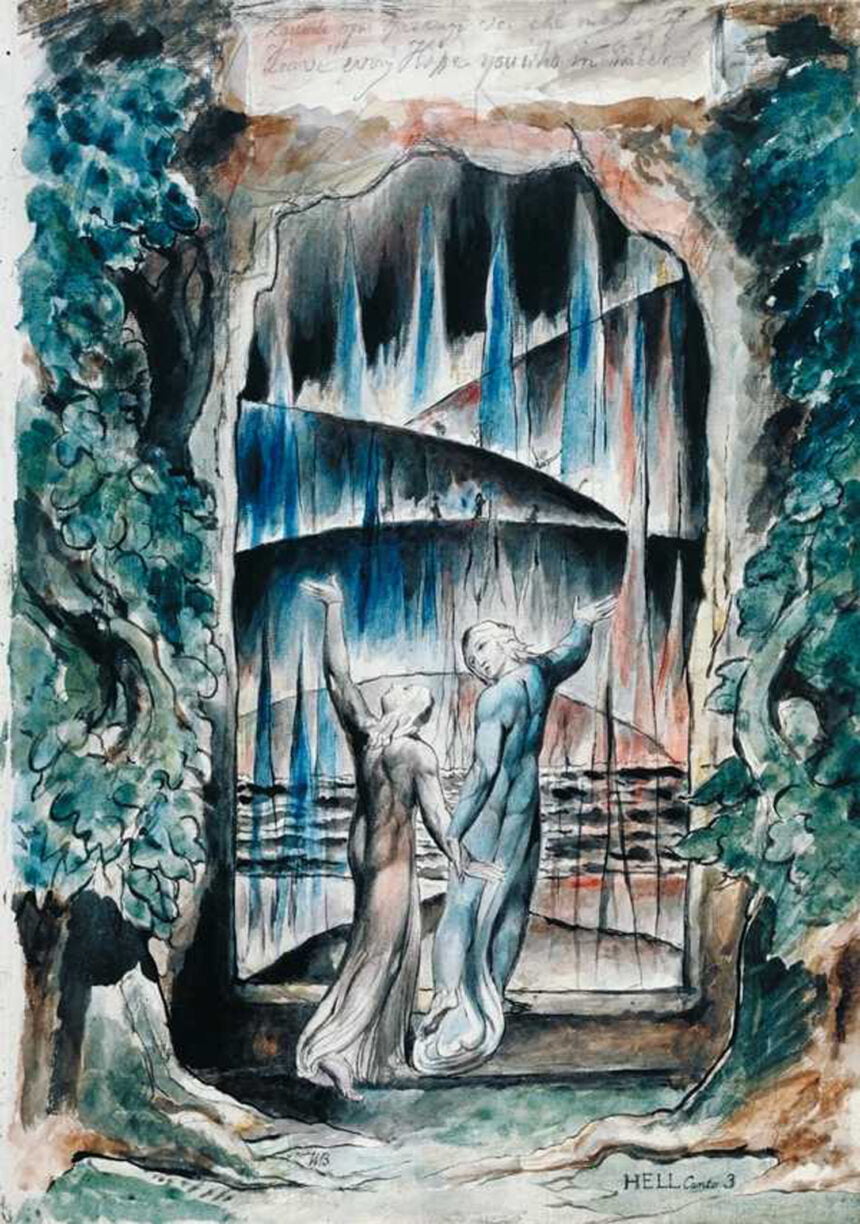

…Mutual forgiveness of each vice,

Such are the gates of paradise…

William Blake, The Gates of Paradise

Once, if I remember rightly, my life was a feast where all hearts opened, and all wines flowed.

One evening I sat Beauty on my knees – And I found her bitter – And I reviled her.

I armed myself against Justice.

I fled. O sorceresses, O misery, O hatred, it was to you my treasure was entrusted!

I managed to erase all human hope from my mind. I made the wild beast’s silent leap to strangle every joy.

I summoned executioners to bite their gun-butts as I died. I summoned plagues, to stifle myself with sand and blood. Misfortune was my god. I stretched out in the mud. I dried myself in the breezes of crime. And I played some fine tricks on madness.

And spring brought me the dreadful laugh of the idiot.

Arthur Rimbaud, A Season in Hell

ARTHUR RIMBAUD

…This is called a sacrilegious lullaby in D-Major…

Bob Dylan, New York Philharmonic Hall, 31/10/1964

Gates of Eden…

Gates of Eden is arguably the song in which Bob Dylan takes his interest in symbolist poetry to the most extreme level. Its collocation of dream imagery is often bizarre and sometimes impenetrable. Under the spell of symbolist poets like Rimbaud and Baudelaire, he appears to be luxuriating in the joy of pure imagery. As with Mr. Tambourine Man, the influence of the psychedelic experience also strongly informs the song. A couple of years later, this kind of culture would enter the popular consciousness through many popular hit singles and albums. But unlike, say, Hurdy Gurdy Man by Donovan, Flowers in the Rain by The Move, Hole in My Shoe by Traffic or The Beatles’ Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds, Gates of Eden is no ‘hippy-dippy’ fantasy. It delivers its philosophical message in an uncompromisingly harsh tone, almost in the manner of an admonitionary sermon.

The song consists of nine four line verses, all delivered in a rather sinister tone. Most of the verses use three rhyming endings, followed by the non-rhymed title phrase, which is made particularly dramatic by this effect. Dylan’s delivery is harsh and uncompromising. There is an interesting contrast in cover versions by Bryan Ferry and Ralph McTell, both of whom approach the song with a kind of hushed awe. The song’s attractive melody is brought out in these versions and more specifically in an instrumental reading by the Moore Trio. Dylan himself has usually stuck to the original acoustic arrangement in his many live takes on the song, although he did briefly try an interesting rock version in 1988 at the beginning of the Never Ending Tour. But the song is usually stripped to its bare musical bones in Dylan’s performances, thus placing emphasis on both the fantastical imagery and the philosophical points Dylan is making.

Gates of Eden in its time

It is important to place Gates of Eden in its historical context. In 1965-66 the shadow of the Cuban Missile Crisis still fell over a world which had trembled at its implications. In A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall Dylan had produced a direct and extremely vivid picture of the horrific cataclysm that the world was then facing. By now, however, the responses to humanity being on the edge of destruction tended to try to identify the socio-political mentality that had brought about the crisis. The conclusion that many young people in the 1960s reached was that the apparently bland surface of ‘official culture’ concealed insane ideologies that threatened the entire human race with destruction. Therefore, it seemed that breaking down all existing social conventions was now necessary. For this confused and angry generation, the lyrics of songs like Gates of Eden, despite displaying irrational logic and extraordinary juxtapositions, made more sense than the speeches of Lyndon Johnson, Barry Goldwater or Richard Nixon. Here, as with other contemporary songs like It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding), Tombstone Blues, Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream and On the Road Again, Dylan mixes surreal and apocalyptic images with an implied critique of the dullness and conventionality of American society.

As Dylan delivers it, Gates of Eden is an angry song. Despite its apparently weird irrationality it expresses the confusion of the post-Missile Crisis world with great eloquence. The opening line immediately introduces us into its dream-logic. Dylan begins by spitting out …Of war and peace the truth just twists… The rather ungrammatical statement takes us by surprise. But it is not only grammatical sense that has broken down in the song’s post lapsarian dream world. The singer is on a mission to redefine the nature of truth itself – a truly philosophical enterprise. The line ends …its curfew gull it glides… This is immediately puzzling. Does ‘it’ refer to the notion of ‘the truth’ presented here? And what on earth is a ‘curfew gull’. The word ‘curfew’ suggests a repressive society and birds certainly do settle down at night as if they are obeying a ‘curfew’. The phrase seems to indicate that Dylan has been experimenting with ‘automatic writing’, a technique beloved of the Beat poets intended to produce juxtapositions of words from the subconscious. Perhaps Dylan is suggesting that populations which might be ‘flying free’ have a ‘curfew’ of darkness (or ignorance) imposed on them. But this kind of language does not invite definitive interpretations.

Most listeners, however, will gloss over the line as the imagery in the next two lines is so powerfully and brilliantly visual: ..Upon four legged forest clouds the cowboy angel rides/ With his candle lit unto the sun, though its glow is waxed in black… The outlandish ‘four legged forest clouds’ paints a surreal picture of a world in which nature itself has been ‘turned upside down’ – as if the clouds have taken on the shape of a great threatening beast. This recalls the nightmarish image of nuclear mushroom clouds looming overhead. The figure of the ‘cowboy angel’ recalls that of the hilarious character Major Kong in Stanley Kubrick’s devastating anti-nuclear satire Dr. Strangelove (released in 1964, the year Gates of Eden was composed) who goes down with the bomb that will trigger Armageddon. The image that follows – of a candle lit ‘into the sun’ seems strangely pointless. The brilliantly suggestive ‘its glow is waxed in black’ may suggest that the sun itself is blackened and dead. The use of ‘waxed’ is particularly clever as the term refers both to one of the phases of the moon and to the making of candles. Yet we are then told that the picture of a distorted world does not apply …’Neath the trees of Eden… Dylan thus immediately sets up the notion of ‘Eden’ as being in opposition to the dystopian scenario he has created.

‘Eden’ of course refers to the Garden of Eden, the mythological location where, according to Genesis, Adam and Eve began the procreation of the human race. According to the Judeo-Christian tradition, it was in Eden that the ‘fall of man’ into sinful ways began. In the great epic poem Paradise Lost John Milton describes this process in intimate detail. The notion of ‘Eden’ has been expanded over the centuries to describe a wonderful or paradisiacal location or a blissful state of mind. It seems that Dylan is now focusing on the notion of Eden as a place of innocence – a kind of Utopia which is simultaneously an individual state of idyllic harmony and delight. The hippie generation that followed in Dylan’s wake may be said to have been reaching out towards this ideal state. As Joni Mitchell sang in her celebration of Woodstock, the most public manifestation of countercultural ideals: …We are stardust, we are golden/ And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden…

More surreal images follow in quick succession. We hear that …the lamppost stands with folded arms, its iron claws attached/ To curbs ‘neath holes where babies wail, though it shadows metal badge…. This scenario can be interpreted in a number of ways. Grammatical and logical sense seems to have broken down. We appear to be in some kind of nightmare in which mechanical objects have come alive in a very threatening manner. A world on the edge of losing all meaning. This is emphasized by the ominous denouement, with its powerful internal rhymes: …All in all can only fall with a crashing but meaningless blow/ No sound ever comes from the Gates of Eden… Meaninglessness, it seems, is the ultimate potential terror. After the coming apocalypse, no one will be left to make moral judgements. They will, in fact, be irrelevant. Eden itself will be empty.

In the next four verses, we meet representatives of military, religious, and political hierarchies, all of whom are out of their depth as they fail to deal with a world spinning out of control. There is a ‘savage soldier’, a representation of the military, who, rather than dealing with any existing problems, …just sticks his head in sand and then complains/ Unto the shoeless hunter who’s gone deaf… In a wonderfully funny lampoon of religious and mystical fakery we see …Aladdin and his lamp… who …sits with Utopian hermit monks/ Side saddle on the golden calf… The surreal reference to riding ‘side saddle’ depicts these bizarre devotees as if they are figures from a crazy psychedelic Western. The political establishment – personified as ‘relationships of ownership’ are condemned to …act accordingly and wait for succeeding kings… In each case, these sadly deluded and confused figures are brought down to earth by the harsh reality that the singer keeps emphasising. Dylan licks his lips around the deliciously alliterative …Upon the beach where hound dogs bay at ships with tattooed sails/ Heading for the Gates of Eden… He concludes that the ‘promises of paradise’ that Aladdin and his gang have made are laughable. Ironically, the one mocking laugh will come from the place where political positions are meaningless: …There are no kings inside the Gates of Eden…

In some wonderfully funny lines Dylan encapsulates the paranoia of the ‘straight world’ in the face of the burgeoning counter culture: …The motor cycle black Madonna two wheel gypsy queen… he sings, delighting in the accumulated adjectival nouns …And her silver studded phantom cause the grey flannel dwarf to scream… The ‘grey flannel dwarf’ (whose reduced stature is, we may assume, more mental than physical) is a stereotyped representation of a conformist – clearly a relation of ‘Mr. Jones’ from next year’s Ballad of a Thin Man. The ‘dwarf’ is then seen to pay obeisance to the …wicked birds of prey/ Who pick up on his breadcrumb sins… The suggestion seems to be that such representatives of ‘the establishment’ are consumed by religious guilt. However Dylan concludes in no uncertain terms that the feeding of ‘breadcrumbs’ is essentially a waste of time as…there are no sins inside the Gates of Eden…

This final line presages the philosophical conclusions that now come to dominate the song, perhaps most effectively in the seventh verse, which begins with a strong suggestion of corruption: …The kingdoms of experience in the precious winds they rot… followed by a beautifully balanced expression of pointlessness: …While paupers change possessions, each one wishing for what the other has got… Meanwhile …the princess and the prince discuss what’s real and what is not… But philosophy itself is futile as …It doesn’t matter inside the Gates of Eden…

In the following verse this sense of futility is taken to the logical extreme. We are told that …friends and other strangers from their fates try to resign… another pointless strategy, as one cannot ‘resign’ from one’s fate. Dylan follows this by what is perhaps the song’s most devastating indictment of the inaction of the rulers of the world in the face of impending cataclysm: …leaving men wholly, totally free… he sings, building up the emphasis with the harsh staccato double positive …to do anything they wish to do but die… as if they are trapped in some horrific version of purgatory. Finally he reminds us that …there are no trials inside the Gates of Eden… Dylan’s ‘Eden’ is far removed from the judgmental notions of heaven, hell and the afterlife that dominate much Judeo-Christian theology. It appears to represent a place of spiritual truth where ‘there are no trials’ but natural justice reigns.

In the final verse the singer’s lover comes to him and reveals that all of this was a dream. She makes no attempt to analyse the plethora of images we have been presented with, concluding that …At times I think there are no words but these to tell what’s true/ And there are no truths outside the Gates of Eden… Thus the ‘cowboy angel’, the ‘lamppost with folded arms’, the ‘savage soldier’, the gang of ‘Utopian monks’, the ‘Black Madonna’ motor cyclist and the ‘grey flannelled dwarf’ are all figments of her fevered imagination as her mind wrestles with matters of conscience, sin and justice.

Gates of Eden is certainly one of Bob Dylan’s most inscrutable songs. In many ways it is an experimental piece. It throws many distinctive images at us, not necessarily in any logical order. In other songs the imagery would be more ordered and consistent. The musical presentation of such songs would often be more attractive. But here he conveys the illogic of a dream very effectively, while emphasizing the philosophical point that, in the face of political and social corruption and with the human race facing potential destruction, the only rational stance to take is one which abandons the twisted logic of a world in crisis in favour of a return to a place of innocence and purity. Only in this way, it seems, by dispensing with conventional notions of rationality, can the seeker after spiritual truth come to terms with the essentially illogical nature of modern life.

LINKS…..

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply