Minstrel Boy

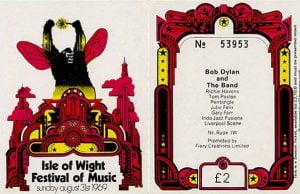

Sunday 31 August 1969. It is 10p.m. and the massive crowd that fills most of a valley at Ryde, Isle of Wight, is getting restless. They have been waiting all weekend for this. On Saturday night The Who, fresh from their epochal appearance at Woodstock less than two weeks ago, had headlined Saturday night with a storming set that included a complete performance of their ‘rock opera’ Tommy. Today had been more of a ‘folkie’ occasion, with Julie Felix, Tom Paxton and Richie Havens all delivering well received shows. But time is marching on now. People are becoming a bit twitchy. Just over half an hour ago the main attraction’s backing musicians The Band had taken the stage and were playing a set of their own material. Some good stuff, if a little intricate and self absorbed for this huge arena. But more and more people were wondering aloud: Where IS Bob?”

There had been so much of a build up. The Festival had been headline news in Britain, where nobody has ever seen a crowd this size at a music event – some said a hundred, some a hundred and fifty thousand. This was many years before festivals were to become multi cultural extravaganzas in which several venues are operating at the same time. Here everything is focused on the one small, and rather shaky looking, wooden stage – which to most of the crowd occupies only a tiny portion of what they can see in the distance. It’s OK for the assorted Beatles, Rolling Stones, Hollywood stars and their ilk who sit in the ‘celebrity arena’ at the front. They have a perfect view but even they must be wondering when ‘the man’ is actually going to appear. Rumours have been circulating all weekend that the Festival will climax in a ‘superstar jam’, featuring virtually every known rock star on the planet.

It had been over three years since Bob Dylan had actually played a concert. The show, the second of two at the Royal Albert Hall on 27 May 1966, was the climax of perhaps the most startling, historic and iconoclastic musical tour of all time in which Dylan, backed by most of what would become The Band, faced a nightly campaign of booing by a section of his supposed ‘fans’ who saw his move into playing ‘electric’ as a commercial ‘sell out’ and a betrayal of what they interpreted as his political leanings, as supposedly displayed in his earlier ‘protest’ material. Even though The Band’s drummer Levon Helm left the tour early (Being unable to stomach the nightly onslaught) Dylan and his musicians had carried on defiantly. Indeed, the opposition from this part of the crowd drove them on to levels of musical and emotional intensity which had never been seen on a rock music stage. After the final show, Dylan had retreated from the public eye, making only brief appearances with The Band at a Woody Guthrie Tribute in early 1968 and at a festival in Mississippi in mid 1969. Even more shockingly for his fans, his music had gone through yet another transformation. His most recent album Nashville Skyline had eschewed the long, mysterious and enigmatic songs of his mid-60s ‘golden period’ in favour of short, sometimes twee was but often infectious country music- influenced ditties with simple, direct lyrics. He had even appeared as a guest on the Johnny Cash TV show, singing his plaintive lovelorn ballad I Threw It All Away.

Bob Dylan

If most of the crowd had watched this performance, or seen the brief interview Dylan had given to TV cameras before the show, they might have been more prepared for what about to occur. But the expectation that he is about to unleash a loud, energetic rock show is still immense. The Beatles had also been off the road for this entire period and the rumour that they might be ‘jamming’ with Dylan was getting the crowd even more excited. Of course, it is highly ironic that the audience actually wanted Dylan to perform the kind of show which he had been lambasted for just three years earlier. But in the context of 1960s musical and cultural revolution, three years was a very long time. Now the entire way that rock shows were staged, along with the expectations of the audience, had changed almost beyond recognition. Advances in amplification had meant that bands could now play very loud music without too much distortion. At their last show at Candlestick Park in August 1966 The Beatles were still playing through PA announcement speakers. Naturally, the screams of their fans completely drowned out the music. Some of the reactions against the rock music that Dylan and The Band played in 1965-66 were actually protests against the poor, often distorted sounds they heard coming out of equipment on which the volume had never been turned up so much. Even now, despite the massive stacks on each side of the stage, the wind could carry the sound away from those at the back. But none of this appears to calm the ardour of the crowd, fired up as they were for Dylan’s appearance.

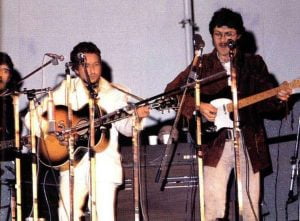

Despite his having apparently ‘disappeared’ into his rural retreat for several years, in 1969 Bob Dylan was at the absolute height of his cultural influence. But he certainly never had a ‘tie dye’ or ‘psychedelic’ period. He came from a slightly older musical generation whose music was firmly rooted in traditional forms. Indeed, the preponderance of studio effects in albums like The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper seems to have set him and The Band on an opposite path, as the highly stripped down John Wesley Harding and The Band’s groundbreaking and quietly impressive Music from Big Pink had demonstrated. Yet when he finally steps onto the stage, dressed in – of all things at such a huge gathering of ‘freaks’ – a white suit – there is a ripple of surprise. He mumbles a hello to the crowd and then is straight into a sweetened, countrified version of 1965’s She Belongs to Me, which begins with the lines …She’s got everything she needs/ She’s an artist, she don’t look back… There will, indeed, be no looking back. In comparison to the wild eyed, wild haired spaced-out screaming poet of ’66, Dylan is reserved and modest. He wears a short beard that makes him look a little like a travelling preacher. At the end of the number he merely mutters …Great to be here….sure is…..

With barely a pause, we are into the next number, a riveting and heartfelt version of I Threw It All Away. By now the crowd cannot have failed to notice that Dylan is singing not in the screechy adenoidal tones he is famous for but – as in Nashville Skyline – in a deep, resonant croon. Although these are the same musicians Dylan played with three years earlier, The Band’s sound has also evolved, from the ‘full frontal musical attack’ of those days to a uniquely tasteful and restrained fusion of country, blues and light funk. Having set the template for what would become ‘heavy rock’ Dylan and The Band have now moved decidedly away from such styles and are expressing through their music an amalgam of American traditions that would later be given the label ‘Americana’. Many observers had been amazed that Dylan had the willpower and strength to complete the gruelling ’66 tour. That tour, especially in the famous climactic moment of the Manchester show where Dylan responds to the catcall of Judas! from an audience member with the most venomous and powerful Like a Rolling Stone ever, has gone down in history as one of the most important in rock history. But in some ways Dylan’s next transformation into the ‘down home’ and rather respectable figure he presents himself as at the Festival is equally iconoclastic and myth-shattering. At the very height of his fame and influence over the ‘love generation’ Dylan quite deliberately presents himself as looking and sounding very much like – whisper it – one of their parents. This is, of course (just as it was in ’66) a kind of game he is playing with the audience. He has indeed always displayed a tendency to avoid ‘looking back’ and has generally delighted in what can only be called ‘perverse’ presentations of his art – always giving the audience what they least expect.

How much of this was communicated to the huge crowd is, however, open to question. In general the reviews of the show were poor and many fans came away disappointed. Dylan only played for an hour – in fact a normal length for a festival set but a big letdown for all of those who had waited so long to see him. His manner in his limited stage announcements was taciturn, even shy, reminiscent perhaps of Elvis Presley – who, despite his role in kick starting rock back in the ‘50s, was hardly a counter cultural hero. There was a growing suspicion that Dylan – like Elvis before him – had rejected any role as a cultural rebel and had ‘joined the establishment’. In 1969, such a perception was a serious matter indeed.

It may also be true that many of the crowd would not have heard the music especially well, given that so many of them were far away from the stage. And there is no doubt that the music did sound rather strange and unfamiliar.. The version of Like a Rolling Stone is a world away from the vicious attack of ’66. Here Dylan treats it almost as a joke, enjoying his exchange of harmonies with members of The Band and delivering the lyrics in a slightly offhand manner. Once the message of the song was an affirmation of how tough and admirable it was to be a rebel against society’s norms. Now it becomes a jaunty ‘singalong’ – almost a parody of itself – as if its essential message has, in those momentous three years, been changed into something entirely different. Dylan is now facing a hundred thousand ‘rolling stones’.

Despite the lack of enthusiasm for the show demonstrated by the press and the fans at the time, the Isle of Wight concert has certainly stood the test of time. Four of the tracks later appeared on Dylan’s much maligned Self Portrait album in 1970. For many years the entire show circulated as a bootleg before it was finally released as a ‘free’ extra disc added to the Another Self Portrait segment of The Bootleg Series. Heard in pristine sound, the performance is uniquely memorable. It would be another four and a half years before Dylan would return to performing regular shows. But the gigs on the 1974 tour with The Band sounded nothing like this. By then The Band were in decline as a unit, as internal disputes and substance problems had begun to pull them part. On that tour the attempt to ‘attack’ the songs in a more conventional ‘rock’ manner comes over as somewhat contrived, and never approaches the intensity of the ’66 gigs, despite returning to something more like the style of that era. Here, and only here, does Dylan play a show in which he effectively trades harmonies with The Band’s three great singers – Richard Manuel, Levon Helm and Rick Danko. The Band play with great subtlety and ingenuity. This is also the only show in which Dylan uses his Nashville Skyline voice throughout.

The arrangements of the songs are also unique. The languorous, even luxurious versions of two songs from John Wesley Harding – I Pity The Poor Immigrant and I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine – give a tantalising glimpse of what that album would have sounded like if The Band had played on it. Garth Hudson’s prominent accordion on Immigrant is highly evocative, backing Dylan’s passionate delivery. In Augustine Dylan rides the staccato rhythm of Levon Helm’s drums to a similarly moving effect. On a lively I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight the choruses are greatly enhanced by The Band’s harmonies. One Too Many Mornings – which had been transformed from an acoustic ballad to an expression of electronic rage in ’66 – now becomes a country song, again distinguished by the backing vocals on the choruses. On Maggie’s Farm, Highway 61 Revisited and a very rare Mighty Quinn, the musicians certainly ‘rock out’, but in a way that is tempered strongly by The Band’s sub-funk rhythms. Robbie Robertson’s tasteful and sparing lead guitar fills distinguish all the songs with great fluidity. Lay Lady Lay – a recent major hit single for Dylan in the UK – is perhaps closest to the album version. The show ends with a crowd pleasing and rather raucous reading of Rainy Day Women Nos 12 and 35, with the whole multitude naturally wishing that ‘everybody must get stoned’ in unison.

Despite The Band’s musical and vocal dexterity, arguably the finest segment of the show is the four song acoustic set, in which Dylan plays solo and sings – for the only time as an ‘acoustic’ artist – using what was then his ‘new voice’ . His rendition of the traditional Wild Mountain Thyme – a favourite of his in different phases of his career – is quite stunningly sustained, while To Ramona suits the new style perfectly. A light and ‘modest’ Mr. Tambourine Man makes the song sound like some ancient ballad. But perhaps the outstanding performance is an exquisite and quite beautiful version of It Ain’t Me Babe, a song originally full of sarcasm and denial but which, delivered here in Dylan’s crooning voice, comes over as a playfully affectionate yet somehow sad message to his audience. Despite all the build up and the hype, the song expresses that Dylan is no messiah or prophet of the ‘love generation’. As he delivers the song with such compassion, he is unequivocal that he is really ‘just a guy’.

Perhaps the most telling song of all, however, is the first encore, a one off performance of Minstrel Boy (originally from The Basement Tapes in 1967 and included in this version on Self Portrait). This is a simple, country style, ditty which is dominated by some truly wonderful harmonies by Dylan and The Band. The song is about a character called ‘Lucky’, a busker who is playing music ‘to save his soul’. …I’m still on that road… Dylan reminds us. The message is even clearer here than on It Ain’t Me Babe. Dylan is declaring that he is not any kind of saviour – he is just a ‘simple singer’ playing for pennies. With mock-humility he implores the vast crowd to …let him down easy to save his soul… Only then does he let them chant and sway about getting stoned.

Listening to the concert today is a tantalising experience. It is impossible not to speculate as to what a Dylan/Band tour of say, 1970 or 1971, would have sounded like, especially in terms of how the music and the harmonies might have produced startling new takes on much of Dylan’s back catalogue. But the show stands alone, as a consummate piece of ‘real life theatre’ which deliberately upsets audience expectations. Dylan gives a By uniquely exceptional performance which, despite originally being seen as a massive anti-climax, now stands as one of the most challenging and distinctive shows of his long career.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O88Il38ve0Q

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply