Subterranean….

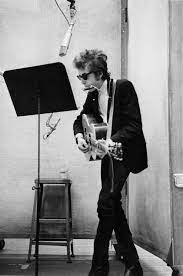

Subterranean Homesick Blues (1965) is Bob Dylan’s coolest, most laconic creation. Perhaps no other example of his work expresses so much in so few words. Dylan is most well known for long songs full of complex word play, but here he demonstrates most eloquently that he is very capable of ‘stripping down’ his use of language. The brilliantly compressed lyrics are highly suggestive and can be interpreted in any number of ways. Every word counts.

The song is infused with Dylan’s characteristically sly and ambiguous humour. One of the key distinguishing marks of his work is the way in which his distinctive turns of phrase have passed into common usage. In no other song is this more true than Subterranean Homesick Blues …You don’t need a weather man to know which way the wind blows… …Twenty years of schooling and they put you on a day shift… and …The pump don’t work ‘cause the vandals took the handles… have acquired deep resonance over the years, capturing the essence of the anti-establishment attitudes of the mid 1960s with Dylan’s uniquely pithy, barbed wit. Whereas Maggie’s Farm lambasts conventional world views by means of the creation of larger than life, symbolic characters, Subterranean Homesick Blues achieves the same effect by presenting a series of sly, knowing aphorisms. It appears to be speaking in its own code, to an audience which shares its values. There is no ‘moral lesson’ to be drawn here, just a series of wry observations on the limitations of modern life as well as its chaotic nature. What it conveys most eloquently over all is a certain streetwise attitude.

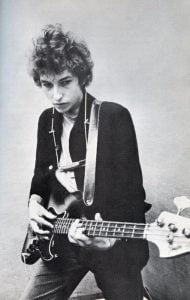

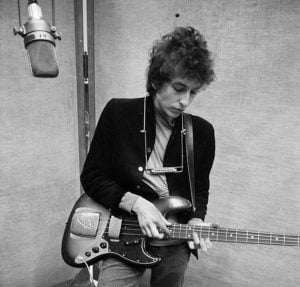

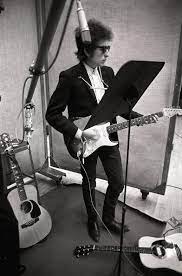

The song has been called the first ‘rap’. It certainly ‘kicks ass’ as Dylan crams in the syllables breathlessly. In terms of composition, execution and use of language it is a giant step away from the story-songs and ‘protest songs’ that made his name. Despite the identification of this recording with his ‘going electric’ it is not his first attempt at a rock song. Towards the end of 1962 he recorded the single Mixed Up Confusion with an electric guitarist, bassist and drummer. But the track had little substance and the single soon vanished into obscurity. As is revealed on Disc One of the extremely comprehensive Bootleg Series release The Cutting Edge 1965-66, Dylan initially cut an acoustic version of Subterranean Homesick Blues. Although this recording has the same basic rhythm as the final take, it is clearly crying out for full band backing. Once the musicians – John Hammond Jr. and Bruce Langhorne on guitars, Frank Owens on piano, John Sebastian on bass and Bobby Gregg on drums – are added, Dylan nails the definitive version in two more takes. There is no question that this is rock’n’roll…

The basic musical and lyrical structure is borrowed from Chuck Berry’s Too Much Monkey Business, a similarly tongue-in-cheek catalogue of the narrator’s woes in which he laments having to do a menial job for a living …Workin’ in the fillin’ station, too many tasks/ Wipe the windows, check the tires, check the oil, dollar gas… He complains about a woman who is trying to tie him down: …Blonde haired, good lookin’, tryin’ to get me hooked/ Want me to marry, get a home, settle down, write a book… The narrator also refers to fighting in World War Two: …Been to Yokohama, been fightin’ in the war/ Army bunk, army chow, army clothes, army car, aah… Berry’s song (which was covered by Elvis Presley, The Beatles and many others) is notable for its lyrical precision, its wry humour, its anti-establishment attitude and its offhand use of short phrases which build up to create a cumulative effect. It expresses similar frustrations to that of the narrator of Eddie Cochran’s Summertime Blues, which cheekily includes a politician dismissing the narrator’s appeal for help in finding a job with the tersely cynical …Like to help you son, but you’re too young to vote…

Subterranean…

By the mid 1960s, as the burgeoning counter culture began to make its presence known, the concerns of listeners had changed considerably. Using Berry’s song as a springboard, Dylan updates the reasons for the protagonist’s complaints using short but extremely memorable phrases. Here, perhaps more effectively than in any other piece from his catalogue, Dylan delights in the use of ironically humorous rhymes. The song begins: …Johnny’s in the basement mixing up the medicine/ I’m on the pavement thinking about the government… With a nod and a wink, Dylan encapsulates the lifestyle of what were then still known as ‘beatniks’ (the word ‘hippies’ had yet to be invented). The first line clearly refers to some kind of drugs, although which kind is deliberately left unspecific. Meanwhile the narrator clearly has some kind of radical politics on his mind. ‘Johnny’ is the quintessential rock’n’roll name. Chuck Berry’s Johnny B. Goode, probably the most covered rock song ever, tells the story of a boy named Johnny who can …play the guitar like ringing a bell…. It has often been seen as a thinly veiled exposition of the story of Elvis Presley and thus of the creation of rock‘n’roll. ‘Johnny’ is the archetypal ‘cool kid’.

The opening lines are very carefully constructed. The use of conventional internal rhyme: …basement/ pavement… is contrasted against the…medicine/ government… which works as a rhythmic echo rather than a ‘true’ rhyme. This adds much to the irony of the lines. Dylan’s sheer audacity in rhyming the two words suggests a scenario in which everything is slightly skewed. The juxtaposition of ‘medicine’ and ‘government’ is ironic in that our narrator is unlikely to be conducting any educated political analysis. The narrator sounds pretty frenetic and wired up, as if he’s ingested a fair amount of Johnny’s ‘medicine’ already. Thus, in just the first two lines, Dylan delivers the song’s first ‘in joke’, which in itself appears to imply that political protest in itself is probably futile. The narrator and Johnny are starting their ‘revolution’ in their own heads.

We are then presented with a series of four internal rhymes: …Man in a trench coat, badge out laid off/ Says he’s got a bad cough, wants to get paid off… This short description suggests a rather shady drug dealer, or possibly a corrupt cop whose ‘badge’ has been laid off. These pithy lines build up towards the recurring cry of …Look out kid!… which begins the first of the five line ‘choruses’ that are alternated with the four line verses. This gives the song a rather ‘jerky’ and unsettling rhythm which is highly appropriate for the subject matter. It is followed with the gloriously ambiguous …it’s something you did/ God knows when but you’re doing it again… Dylan appears to be addressing a ‘kid’ who personifies youthful rebellion. The lines are a perfect summation of the feelings of a teenager who feels he is being ‘bugged’ by adults. But the ‘kid’ is somewhat naive. We are told that another dodgy character, the ‘man in the coonskin cap’, wants …eleven dollar bills/ You only got ten…. So the ’kid’ is advised to …duck down an alleyway… to escape from his wrath.

A character called ‘Maggie’ then appears (clearly not the woman from ‘the farm’) warning that the police may try planting drugs on them. We also hear that …the phone’s tapped anyway, Maggie says that many say/ They must bust in early May, orders from the D.A…. Clearly this is a tough urban scenario. He is warned …Don’t carry no dose… (presumably drugs) which is rhymed with …Better stay away from those who carry round the fire hose…. a reference to the US police’s draconian use of fire hoses against Civil Rights protestors. The verse ends with more laconic warnings: …Keep a clean nose, watch the plain clothes/ You don’t need a weather man to know which way the wind blows…. In other words, some things which cannot necessarily be stated directly are obvious to those who are ‘in the know’. This might be a motto for the whole song. The ‘kid’ is thus told he needs to become street wise or ‘hip’ to the dangers of the bohemian life style. But the final line also has deeper resonances. In many ways it sums up the whole attitude of what became known as the ‘alternative society’. To those who were ‘in the know’ certain things of which those in the ‘straight world’ were unaware were in fact so obvious that they were unstated. Subterranean Homesick Blues is perhaps the first mainstream rock song to utilise this ‘secret hip language’, which would soon become very widespread.

The rest of the song consists entirely of advice to ‘the kid’, whose life is now described as a rather tedious round of duties: …Get sick, get well, hang around an ink well/ Ring bell, hard to tell, if anything is gonna sell… Dylan delights in the way the insistent rhymes push the song forward in short staccato bursts. Using the world-weary comic disillusionment of Too Much Monkey Business as his starting point, he presents us with a barrage of mid-60s hip argot. He delivers the increasingly manic lines in an offhand, monosyllabic near-spoken drawl which would later become a model for singers like Lou Reed, not to mention many rappers. The ‘normal’ life that ‘the kid’ is trying to escape from is presented as consisting of endless tedium. A world in which one gets sick, gets better, gets a job, a mortgage, a funeral… Everything seems to be pointless and superficial. The reference to the ‘ink well’ may be a dry summary of the lack of inspiration provided by the education system, or it may just be playful nonsense. The song treads a thin line between social commentary and Beat-style word association. Sense and nonsense are mangled together. Only in this way can ‘the kid’ receive any advice that will be meaningful to him.

The lines that follow introduce apparently random elements of alliteration as the singer wraps his tongue around: …Try hard, get barred, get back, write braille

Get jailed, jump bail… It seems that whatever ‘the kid’ does will result in failure and frustration. The cynical resignation of …join the army if you fail… (another echo of Berry’s song, whose narrator is in …Yokohama, fighting in the war…) works as a sly dig at the way that the military recruits rootless young men as ‘cannon fodder’. The narrator warns ‘the kid’ that he will also be used and exploited by those who, like him, live on the edge of the law: …losers, cheaters, six-time users… Dylan turns the colloquial expression ‘three time loser’ inside out here, suggesting connotations of drug abuse. We are told (rather hilariously) that these dubious characters are …hanging round the theaters…

At this point the narrator may be beginning to turn the venom of the song on himself. Perhaps he himself is ‘the kid’; beset by all kinds of chancers and weirdos who will try to ‘bend his mind’. And perhaps, in the deliriously silly lines that follow, he is warning himself about the dangers of ‘women on the make’ who also wish to exploit him: …Girl by the whirlpool, looking for a new fool…. The advice given to ‘the kid’ is to always stay true to himself …Don’t follow leaders… he is told. This is rhymed with the rather gloriously surreal …Watch the parking meters… as if the meters are somehow moving around, ‘keeping an eye’ on him. This line is perhaps the most well known in the song. We may speculate that Dylan is denying the role of ‘leader’ of his generation. Or he may be telling his followers to reject authority figures in general. Subterranean Homesick Blues is certainly an attack on the ideals of the ‘American Dream’, an ideology which suggests that any person can ‘make it’ to wealth and fame purely through hard work and application. One is reminded of Willy Loman’s reaction in Arthur Miller’s tragic deconstruction of the American Dream Death of a Salesman. When his wife points out that, after years of struggle, they have finally paid off their mortgage, Willy laments that now their children have grown up and moved out:

…Figure it out. Work a lifetime to pay off a house.

You finally own it, and there’s nobody to live in it…

In Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby the protagonist Jay Gatsby pursues a different kind of ‘Dream’. Although he is very rich he is never satisfied with wealth alone and pours all his energy into a futile attempt to reconnect with Daisy, his lost love:

…I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night…

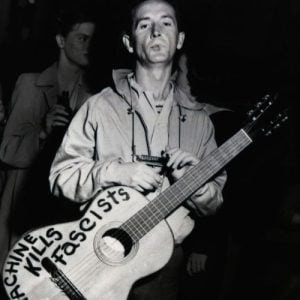

WOODY GUTHRIE

In Woody Guthrie’s famous ‘patriotic’ anthem This Land is Your Land the singer pursues an alternative version of the American Dream; one that exults in the glories of the landscape of the country. As he ‘roams and rambles’, he extols the beauties of its landscape:

..When the sun came shining, and I was strolling,

And the wheat fields waving and the dust clouds rolling,

As the fog was lifting a voice was chanting:

This land was made for you and me…

.

But in verses that are often omitted from performances of the song, Guthrie focuses on the dark side of the Dream:

.. As I went walking I saw a sign there,

And on the sign it said “No Trespassing.”

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing.

That side was made for you and me.

In the shadow of the steeple I saw my people,

By the relief office I seen my people;

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking

Is this land made for you and me?…

Dylan sums up the shallowness of the concept of the Dream with cutting cynicism and barbed wit in the song’s brilliant final verses, which begin by delivering an amazingly concise account of the life of ‘the average American’. Here the rhymes are delivered like rapid machine gun fire. The process of growing up is reduced to …Get born, keep warm, short pants, romance… followed by …Learn to dance, get dressed, get blessed, try to be a success…. This is followed by a little advice to ‘stay on the straight and narrow’: …Please her, please him, don’t steal, don’t lift… leading into the killer line …twenty years of schooling and they put you on a day shift… Thus the hollowness of the Dream is exposed here in these brutal couplets. But the lines have an even wider relevance. They express the feelings of a generation which was about to launch a mass rebellion against the grey dullness of conformity in a way that resonated with young people across the world. They also expose the contradictions between being brought up in a supposedly liberal education system and having to compete in the ‘rat race’ of the job market. Many of Dylan’s listeners were determined that their lives would be more colourful and adventurous than those who merely found themselves trapped ‘on a day shift’.

The final lines of the song end in a suitably surreal denouement. In the light of the oppression he faces the ‘Kid’ is advised to disappear into the subterranean realms of what was soon to become known as ‘the underground’: …Better jump down a manhole, light yourself a candle… is rhymed with the tongue in cheek …Don’t wear sandals, can’t afford the scandals… a reference to the conventional disapproval of the kind of ‘weird’ clothing that ‘the Kid’ is wearing. The final piece of advice is suitably ambiguous. Dylan sings: …Don’t wanna be a bum, better chew gum… In fact the whole song is being delivered in truly ‘gum chewing’ laconic American style. Lastly we are told that …the pump don’t work ‘cause the vandals took the handles…. a wonderfully graphic image of urban decay. The ‘Kid’ will not be able to rely on exterior help. He will have to figure out his way through the confusion of his life in the modern world himself. He may succeed or fail. But at least he will have avoided becoming a mere cog in the ‘production line’ of modern capitalism.

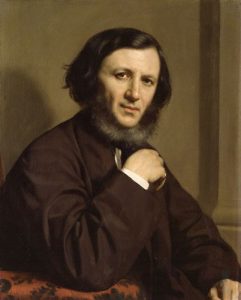

ROBERT BROWNING

As Michael Gray first pointed out, these lines also have a strong resonance with Robert Browning’s poem Up at a Villa – Down in the City. Dylan seems to have been particularly attracted to Browning, whose poems are often written in the voice of an imaginary persona, a technique Dylan uses frequently. In this case, however, Dylan seems to have ‘borrowed’ some of Browning’s rhymes from the poem:

…Look, two and two go the priests, then the monks with cowls and sandals,

And the penitents dressed in white shirts a-holding the yellow candles;

One, he carries a flag up straight, and another a cross with handles.

And the Duke’s guard brings up the rear, for the better prevention of scandals:

Browning’s poem is a fairly light hearted comparison between an Italian city and the countryside. It is remarkable how Dylan has transmuted these distinctively musical rhymes into a song with entirely different subject matter.

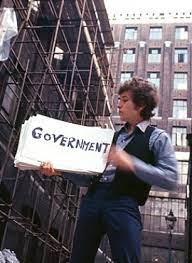

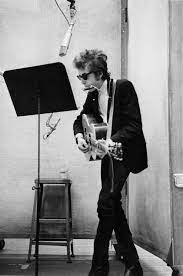

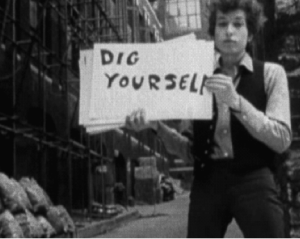

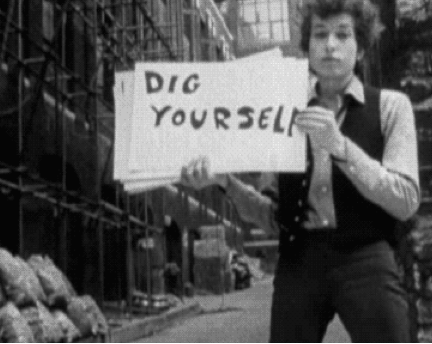

Subterranean Homesick Blues is also renowned as the progenitor of the modern ‘pop video’. The sequence which appears at the beginning of the film Don’t Look Back (released in 1967) has become so iconic that it has inspired a multitude of imitators in many different contexts. The clip was filmed in monochrome by director D.A. Pennebaker in a London alleyway behind the Savoy Hotel, which was undergoing building work, during Dylan’s final acoustic tour of Britain in June 1965. The first shot we get is of some building materials. Then the camera pulls back and adopts a static position. Allen Ginsberg can be seen in the left hand corner of the frame chatting to Dylan’s compatriot Bob Neuwirth. Dylan stands impassively, occupying the right side of the frame, making no attempt whatsoever to mime the lyrics. He holds a large pile of white cards, on which are written short (mostly one word) extracts from the lyrics. While the song plays Dylan throws these cards down. He remains ‘super cool’ throughout, maintaining his deadpan expression. At first the words on the card follow the song’s rhymes: ….‘BASEMENT’, ‘MEDICINE’, ‘PAVEMENT’, ‘GOVERNMENT’…. The film follows this pattern for the first minute or so. Then Dylan begins to change some of the words or deliberately mis-spell them. ‘Success’ becomes ‘SUCKCESS’. ‘Parking meters’ becomes ‘PAWKING METAWS’. ‘D.A’ is spelled out as ‘DISTRICT ATTORNEY’. Other messages are also interjected. ‘WATCH IT’ appears, later ‘DIG YOURSELF’ and finally ‘WHAT??’ Finally Dylan merely walks out of shot and Ginsberg and Neuwirth retreat into the distance. The distinctiveness of the clip lies in its casual, off hand atmosphere, which mirrors Dylan’s delivery perfectly. The trick of ‘throwing down the cards’ is a partial guide for the viewer to the song’s scattergun lyrics, but also leads us in other directions. The phrase ‘DIG YOURSELF’ is perhaps the best summation of the kind of ‘personal revolution’ that Dylan is now presenting. Everything about the song is a cry for personal liberation, but its execution (along with that of the video clip) is executed with a knowing sense of cool that makes it still compelling viewing today. The YouTube video of the song had, by October 2021, attracted over eight million viewers.

Subterranean Homesick Blues is one of Dylan’s best known songs. It was released as a single in March 1965, reaching no 39 in the US Billboard charts and the top ten in Britain. Since its release as the opening track on 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home it has appeared on numerous ‘Greatest Hits’ compilations. Yet the song has rarely been a staple of Dylan’s live shows. Apart from a brief revival in 2002, the majority of its live performances occurred in the early years of the Never Ending Tour. It was used as the set opener for all the 1988 shows and, rather less frequently, in the immediately succeeding years. By opening with this iconic song, Dylan clearly signalled that the ethos of the early NET, with its small, tight band and shorter set lists, was very much a ‘return to basics’. However, although the performances were always lively and committed, the song does not seem to have been one which Dylan has been able to explore greatly in the live context. In its recorded form it is just short of two and a half minutes long. In the live shows it often lasts between four and five minutes, largely because of the instrumental breaks that are added between the third and fourth verses and at the end of the song. Although it provides an exciting opening to the early NET shows, it is presented as a conventional rock song. Dylan never really captures the freewheeling insouciance of the recording. Given the form of the song, it is also one which is difficult to devise alternative arrangements for. It is also arguably very much a ‘young man’s song’ as it deals so specifically with the trials and tribulations of youth.

Like all classic Dylan songs, Subterranean has been subjected to many cover versions. The song, with its powerful dynamics and strong beat, is always a handy addition to any rock show. But few cover versions have really added much to the original. Exceptions include the version on Harry Nilsson’s 1974 album Pussycats, featuring producer John Lennon on backing vocals. The Nilsson/Lennon version adds a dynamic and slightly different beat and impassioned singing. Perhaps the most effective covers, however, are from two rock bands who have integrated elements of rap music into their sound, Red Hot Chilli Peppers and Rage Against the Machine. In these versions the use of rapping brings the lyrics into focus against harsh, uncompromising beats. In many ways the song was ahead of its time in the way the lyrics are structured, although Dylan (ever the music historian) has insisted that it was in fact inspired by ‘scat songs from the 1940s’. The song also needs to be performed with a mixture of anger, irony and sheer ‘cool’ which a conventional rock presentation does not always do justice to. Despite it being one of Dylan’s ‘signature songs’ – and certainly one of the tracks one would play to a ‘Dylan novice’ to illustrate the singer’s mastery of words and music – it stands alone in Dylan’s work as uniquely concise and impressively eloquent snapshot of the turbulent period from which it first emerged. Yet its explosion of barbed wit and knowing asides still resonate today.

ANY COMMENTS, THOUGHTS ETC….

YOU CAN EMAIL CHRIS AT chrisgregory@myloss.net

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply