…The poet, therefore, is truly the thief of fire.

He is responsible for humanity, for animals even; he will have to make sure his visions can be smelled, fondled, listened to; if what he brings back from beyond has form, he gives it form; if it has none, he gives it none. A language must be found…of the soul, for the soul and will include everything: perfumes, sounds, colours, thought grappling with thought…

Arthur Rimbaud, Letter to Paul Demeny, 1871

……Holy the sea holy the desert holy the railroad holy the locomotive holy the visions holy the hallucinations holy the miracles holy the eyeball holy the abyss!

Holy forgiveness! mercy! charity! faith! Holy! Ours! bodies! suffering! magnanimity!

Holy the supernatural extra brilliant intelligent kindness of the soul!

Allen Ginsberg, footnote to Howl, 1955

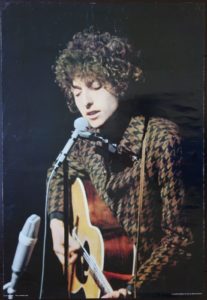

Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands – which takes up the whole of Side Four of Bob Dylan’s classic 1966 double album Blonde on Blonde – is an ambitious visionary work, drawing on the influence of romantic and symbolist poetry, reflected through patterns of modernist complexity. It is a song that appears to begin in ‘mid stream’. It would be quite possible to rearrange the verses without greatly altering its effect or the meaning. Its seductive waltz melody in 6/8 time establishes the musical theme that will continue throughout. The voice is calm, measured, as Dylan enunciates every word clearly and methodically. The tune rocks us backwards and forwards like the motions of waves which sometimes seem to be rising to crescendos that they never quite reach. The vivid, striking and mysterious onslaught of images takes us on a journey to the farthest edges of the known universe and the deepest recesses of our minds. We can stare down into those waves, hoping to see a clear picture but the sea is forever changing. The narrator is like Narcissus, staring down into the water, desperate to see his own beautiful face. But he never sees a clear or definitive image of himself. Meanwhile, the waves roll on, always chopping and changing, tied to the pull of the moon and the inexorable passage of time. When it finally ends after ‘only’ eleven minutes, one has the impression that it could go on forever.

This is a song that Dylan has never performed in front of a live audience, partly perhaps as a result of its length, but possibly because – unlike virtually every other song he has written – it seems somehow unchangeable. Dylan has said that he keeps adapting his songs on stage in pursuit of the ‘perfect’ version of each one. But here, for once, he seems to have achieved that end in the first recorded version. It could thus be said to be the ‘purest’ of all his songs. You can lie back and feel it carry you away into another world – a kind of luminescent, poetic reality in which meanings are felt in deep emotional rather than intellectually rational ways. And yet it is not an emotionally variable song. It establishes a certain mood and then stays with it. The narrator is both deeply invested in and detached from the surreal, ever-changing plethora of images he presents us with. He is both ‘there’ and ‘not there’ at the same time.

Dylan’s songs of his celebrated 1965-66 period are full of surreal images, unexpected juxtapositions, barbed jokes and pithy observations. Despite this, we can still locate Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues in a ‘semi-mythical’ version of Mexico. Visions of Johanna may be a drug-induced dream but it definitely appears to be taking place in a ‘bohemian loft’. It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) is a kind of existential prayer. Even Stuck Inside of Mobile has a coherent, if scatological narrative. But Sad Eyed Lady is the most difficult of all these songs to pin down. It has been subjected to many – often highly dubious and almost entirely reductive – interpretations. In his 1975 song Sara Dylan himself appears to have ‘confessed’ – in a very rare moment of autobiographical revelation – that the song was written for his wife: …I can still hear the sound of those Methodist bells… he sighs …I’d taken the cure and I’d just gotten through/ Stayin’ up for days in the Chelsea Hotel/ Writing ‘Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’ for you… These lines seem to suggest that Sara had saved him from the perils of some kind of addiction. Yet there is nothing in Sad Eyed Lady that suggests that this is any kind of ‘key’ to the song. It may well be a statement which, like so many of Dylan’s public pronouncements, we can take with a pinch of salt. Testimonies by the Nashville musicians Dylan was working with on Blonde on Blonde have actually established that most of the song was written in the studio while they kicked their heels.

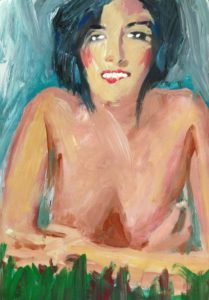

SARA DYLAN IN ‘RENALDO AND CLARA’

It is impossible to deny that Sara herself had a huge influence not only on Dylan’s life but also on his career as a performer and a songwriter. His marriage to her was accompanied by a long ‘rural retreat’ in which he gravitated first towards the shorter, playful songs of ‘The Basement Tapes’, the dense mythological symbolism of John Wesley Harding and later the expressions of domestic bliss on Nashville Skyline, New Morning and much of Planet Waves. Only when his marriage broke up in the mid 70s did he return to the public stage. But although the song was undoubtedly inspired by his love for her, the stream of heartbreakingly beautiful hallucinatory images Dylan presents us with turn the object of his devotion into an emblematic figure, not only of all womanhood but of all humanity. She is an ineffable, indefinable muse. The song is a series of ‘reflections’ – deep meditations on the qualities of the ‘Lady’ which also mirror the state of mind of the narrator. The poet appears to be, perhaps more so than in any of Dylan’s other songs, ‘drunk on words’. In some ways Sad Eyed Lady is a love song to the power of language itself. Meanwhile, those infinitely sad eyes – which contain an indefinable wisdom: a kind of ‘secret knowledge’, perhaps of both beauty and mortality – continue to stare at us, sphinx-like, unmoving.

There is no denouement in the song, no final statement of realisation. We are given no details of the relationship that apparently exists between the narrator and the object of his address. The verses are comprised of descriptions of the ‘Lady’ and incidents that relate to her, interspersed with an appeal to her in the choruses. Each verse ends with an unanswerable question; the first being …Who do they think could bury you… In succeeding verses ‘who do they think’ is repeated, with the lines linked by rhyme or pararhyme. First we get ‘carry you’. Then ‘outguess you’ and ‘impress you’, then ‘kiss you’ and ‘resist you’, then ‘mistake you’ and ‘persuaded you’ and finally ‘employ you’ and ‘destroy you’. But it is obvious that the Lady will not be buried, ‘carried, outguessed, impressed, kissed, resisted, mistaken, persuaded, employed or destroyed’. We never learn who the ubiquitous ‘they’ refers to but we are left in no doubt that the Sad Eyed Lady is a figure who cannot under any circumstances be compromised. She is a pure, shining, star – a figure onto whom all kinds of projections can be made.

Despite the rather anarchic, apparently random, use of imagery in the song, Sad Eyed Lady is also characterised by the use of very rigid patterns of rhythm, rhyme and metre. It contains ten verses, punctuated by five choruses. Each verse has three rhyming lines followed by a non-rhyming line which ends in ‘you’. The first three lines follow the basic ten syllable structure of iambic pentameter while the last line has eight syllables. As with most Dylan songs, there is no bridge section. The words in the chorus do not vary, with ten syllable lines being followed by eight syllable lines. It is this extreme contrast between formality of structure and apparent randomness of imagery which makes the song so entrancing.

The song also has five identical choruses, each of which follows two verses. Here, and only here, does the narrator refer to himself, if in an entirely imagistic way: …My warehouse eyes, my Arabian drums, should I put them by your gate/ Or Sad Eyed Lady, should I wait…. The image of ‘warehouse eyes’ suggests a kind of vast emptiness in the narrator that is waiting to be filled. Yet he is caught in a kind of eternal dilemma. Should he dedicate his poetic and musical soul to her, or should he continue to prevaricate? As listeners we are kept hovering around this existential dilemma. These lines are preceded by the repeated title line, with its mysterious follow up: …Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands/ Where the sad eyed prophet says that no man comes…. The use of ‘where’ rather than, say, ‘to whom’ tends to suggest that he is referring here to the place ‘the Lowlands’ rather than to the Lady herself. Here Dylan appears to be referring to the traditional song The Lowlands of Holland in which a young woman laments that her lover has been press ganged to join the navy and has been sent off to fight. Yet the ‘Lowlands’ referred to in the song appears to have little relation to the country now known as The Netherlands. It is a very indistinct geographical entity, and can be seen as a symbolic or even mythical region. It is in this mysterious place of shadows and mystery that the Sad Eyed Lady apparently resides.

…With your mercury mouth in the missionary times…. Dylan begins, delighting in the alliterative sound of the words as they slide off his tongue. The image of a ‘mercury mouth’ immediately gives us an impression of something slippery, a substance that cannot be dissolved and which slides over the surface of other forms of matter. Something indefinable, mysterious, shining and beautiful in its own way but also potentially poisonous or deadly… Mercury is also the messenger of the gods. Perhaps the Sad Eyed Lady will open her mouth and deliver some revelation, but whatever it is unlikely to be revealed here. ‘Missionary’ has the same number of syllables as ‘mercury’. Its connotations, however, are rather different, suggesting a more rigid intent to persuade or ‘convert’ the narrator, who we assume is aching to kiss that ‘mercury mouth’. But there is also perhaps a sense of fear, that if he does kiss those lips he will be lost, subsumed into ‘the Lowlands’.

The wonderfully translucent simile that follows …With your eyes like smoke… again suggests that she may be able to ‘suck him into’ her consciousness. Dylan piles on the evocative descriptions …and your prayers like rhymes… does, of course, ‘rhyme’ with ‘times’. Perhaps all of these supplications to the ‘Lady’ are prayers, as if the narrator is asking for divine guidance to help him understand this unknowable chimera of a woman. The third rhyming line mixes a concrete image with another simile that emphasises sound: …With your silver cross and your voice like chimes… Perhaps the narrator sees himself reflected in the cross – a symbol, of course, of suffering and redemption and finally of deliverance. In one of Dylan’s last and most famous ‘protest’ songs Chimes of Freedom (1964), he transforms the ‘sound image’ of church bells ringing or ‘chiming’ into an evocative, desperate but perhaps ultimately hopeless plea for a form of universal human compassion. Here again he uses ‘sound images’ in the two similes, reminding us that he is again evoking the ‘music of the spheres’ in order to express the kind of spiritual longing that mere ‘words on the page’ can never do justice to. With her shining cross and her voice like church bells ringing the Lady embodies a kind of spirituality that echoes Ginsberg’s declaration of the universality of holiness, itself deliberately echoing Blake’s famous declaration in his epic poem America that …Everything that lives is holy!….

In the second verse Dylan slides in and out of alliterative expression …With your pockets well-protected at last… he begins…And your streetcar visions which you place on the grass… Perhaps Dylan is now identifying the Lady with Blanche DuBois, the desperately tragic heroine of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. There are also echoes of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass which the great visionary poet claimed to carry in his pocket at all times. In the These I Singing in Spring section of the book he declares that: … Here, out of my pocket, some moss which I pull’d off a live-oak in Florida as it hung trailing down… This is succeeded by one of the song’s most memorably sensual lines: …With your flesh like silk and your face like glass… Here the contrast between ethereal beauty and the impassive stoicism that characterises The Lady is emphasised. The sound of the words ‘silk’ and ‘glass’ further emphasises this disparity. Like Blanche Du Bois, the ‘Lady’ may be, it seems, both seductive and highly dangerous.

In the third verse Dylan throws out even more disparate imagery. First we get more mysterious similes …With your sheets like metal and your belt like lace… The narrator stares at those metal sheets and sees a somewhat wobbly reflection of himself. A belt made of lace is commonly a feature of a wedding dress. The imagery suggests a combination of hardness and softness which is characteristic of The Lady, suggesting that she is a being of great contradictions. In the next line she is said to have a …deck of cards missing the Jack and the Ace… There is only so much, it seems, that she will leave to chance. Those ‘key cards’ are missing from her makeup. We are told she has …basement clothes… and a …hollow face… She dresses down, it seems. Maybe she has been down in that basement with ‘Johnny’ from Subterranean Homesick Blues while he has been ‘mixing up the medicine’ for her. Her entire existence is shrouded in mysteries of one kind or another. Her ‘hollow’ face is one on which the supplicant can superimpose any features he wants. But there is a definite hint of a drug-ravaged visage here. Perhaps the singer has ‘taken the cure’ but in this verse he seems to be imposing his own image upon hers. It is hard for him to see that image clearly, reflected as it is in the shiny metal sheet.

The lines that follow are perhaps the most evocative, with their radical revision of the conventional imagery of love songs. The image of ‘moonlight’ is commonly utilised in the sentimental tradition. The standard Moonlight Becomes You, as performed by Bing Crosby in The Road to Morocco utilises a clever play on words. The effect of the moonlight on the object of the song is ‘becoming’; in the sense that it is suitably flattering. There is also a rather mystical hint that the girl has been transformed into the spirit of the moonlight itself. Dylan’s transposition of this romantic trope is much more direct, with every word suggesting a movement which takes the listener directly into the mystical space that The Lady’s eyes occupy The delicious alliteration of …With your silhouette where the sunlight dims… is contrasted beautifully with …Into your eyes where the moonlight swims… Here the ‘sunlight’ and ‘the moonlight’ are both personified, with one natural phenomenon replacing another. The narrator appears to be reaching out, attempting to grasp the mysterious alchemy of words as they are transformed into poetry. The Lady has become an elemental being. As the sun goes down inside those eyes, which radiate the mystic power of sensual attraction, the moon – the cosmic entity most linked to female fertility and consciousness – literally ‘becomes’ The Lady. She is his light in the darkness, an inexorable force of gravity which draws him to her. The Lady, with her ‘matchbook songs’ and her ‘gypsy hymns’ has become the personification of poetic song itself; the eternal muse which the songwriter must pay homage to in order to arrange words in the multi-dimensional way which defines poetry itself.

The opening lines of the next verse …the Kings of Tyrus with their convict list/ Are waiting in line for their geranium kiss… are often cited as being amongst the most obscure in Dylan’s canon. Tyrus (or ‘Tyre’) is a Phoenician city situated in present day Lebanon. In the book of Ezekiel the King of Tyrus is a rich merchant, the embodiment (as we might put it today) of capitalist greed and immorality. The ‘sad eyed’ prophet Ezekiel identifies the King with Satan. Here Dylan appears to be transposing opposites. The ‘Kings’ have taken many enemies prisoner and are presumably about to execute them. In the song’s most surreal juxtaposition they are, however, waiting for a ‘geranium kiss’. Geraniums are flowers which come up through the winter and are often characterised as ‘hardy perennials’. In these lines the evil Kings appear to be about to be ‘sanctified’ by the intimate touch of these flowers. This encounter appears to be unexpected. The narrator reflects that …You wouldn’t know it would happen like this… but inside the dream world of The Lady’s eyes, lit by that ethereal moonlight, anything is possible. But the question at the end of the verse …Who among them really wants just to kiss you?… hints at The Lady’s powerful erotic allure. This is reinforced by more apparently random imagery, as various aspects of The Lady’s character and history are outlined: With your childhood flames on your midnight rug/ And your Spanish manners and your mother’s drugs/ And your cowboy mouth and your curfew plugs… There are various suggestions of ‘exotic’ sexuality here, as The Lady bursts into ‘childhood flames’, presumably while making love on a floor. The Spanish are famed for their frequent colloquial uses of profanity (the kind that might come out of a ‘cowboy mouth’) while the ‘mother’s drugs’ may refer to some kind of aphrodisiac. The ‘curfew plugs’ may be devices she covers her ears with to blot out the entreaties of those who appear to be unable to resist her.

In the final verses the narrator is utterly drawn into the world inside The Lady’s unblinking eyes. Inside this internal symbolic world, as well as eroticism and magical transformations, we discover images of spiritual desolation: …Oh the farmers and the businessmen, they all did decide/ To show you where the dead angels, where they used to hide… The notion of ‘dead angels’ appears to be a contradiction in itself, as angels are supposed to be eternal beings. The narrator asks …But why did they pick you to sympathise with their side?/ How could they ever mistake you… Clearly The Lady is refusing to co-operate with the attempts by unknown forces of darkness and decay (referred to throughout merely as ‘they’) to co-opt her spiritual power. She remains steadfast throughout, refusing to let them corrupt her. She does not respond to the ‘phony false alarm’ with which they try to shock her into …accepting the blame for the farm… Presumably the ‘farm’ being referred to is owned by the ‘farmers and the businessmen’ who are trying to corrupt The Lady. The image is suggestive of the way that unscrupulous businessmen forced farmers off their land during the 1930s ‘dust bowl’, as immortalised in the songs of Dylan’s mentor Woody Guthrie. But The Lady seems, at least in the dream world that the narrator perceives inside her ‘eyes like smoke’, to have some kind of supernatural power. We hear that she has ‘the sea at her feet’ and that ‘they’ will never persuade her to change, even though she has been left, in a particularly haunting image, with …the child of the hoodlum wrapped up in your arms… Again there are suggestions of a pre-war scenario, with The Lady presumably having been abandoned by a gangster who has left her pregnant. But there is no doubt that she will protect the child with all her love. Perhaps the narrator is identifying himself as this ‘wild child’ and it is only The Lady who can rescue him from the cruelty of the world. In that dreamland, inside her impassive eyes, he has found a safe space.

In the penultimate verse we are given some apparent biographical detail which indeed links The Lady to Sara: …With your sheet metal memory of Cannery Row/ And your magazine-husband who one day just had to go… Sara’s father was a sheet metal dealer and she had previously been married to Hans Lownds, a photographer who worked for magazines such as Playboy. Presumably John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row (set in California in the Great Depression of the 1930s) was one of her favourite books. Only now, as the song reaches its end, does Dylan appear to deal with such ‘real world’ trivia. ‘Lownds’ is, in itself, a compression of ‘Lowlands’. In these lines, perhaps the song’s weakest, it is as if Dylan himself has peeked out from behind all the symbolism for the moment. He is somehow lost for any kind of meaningful symbols and so has to rely on mundane biographical detail. But this in itself is especially touching. For a few moments, he is no longer the great poet but a tongue tied boy trembling in the presence of a love which has overwhelmed him. This is illuminated most eloquently by the moving simplicity of what follows: … And your gentleness now, which you just can’t help but show…. surely the song’s most heartfelt, genuinely emotional, line. In this moment all the poetic pretensions of the song dissolve and the singer conveys the true depth of his love.

…Now you stand with your thief…. the final verse begins. There is little doubt that Dylan himself is the thief. Throughout his career he has followed Rimbaud’s dictum (derived from the myth of Prometheus) that the poet must be ‘the thief of fire’. He must not be afraid to ‘steal’ ideas (or whole lines from other poets) if necessary. The dictum ‘Love and Theft’ has been a feature of his entire career. He jokes with her that …You’re on his parole… when really he surely knows that the reverse is true. Throughout the song he has been humble, indeed awed, in her presence. Now, for just a moment, he pretends that he has ‘stolen’ her (perhaps from that ‘magazine-husband’) and that he is allowing her some measure of freedom. In reality it is he who, like a traditional romantic lover, is down on his knees begging her to accept him. Finally he can do nothing but prostrate himself before her. As he later sings in Sara, in perhaps the most self-deprecating line of his entire career …You must forgive me my unworthiness… In the final images of the song he sanctifies her …With your holy medallion which your fingers now unfold… To him, she personifies that holy medallion. She will be his saviour, the source of ‘the cure’ for all of the poisons – chemical or otherwise – which he has ingested. In the transcendent final lines he personifies her with a brilliantly haunting summary of her very essence and existence: …With your saint like face and your ghost like soul/ Who among them could ever think he could destroy you?…

The Sad Eyed Lady is a female archetype, a secular saviour, an object at which this word-drunk poet can throw any mad metaphor or simile. She allows him into the Lowlands, ‘another world’ in which – as he will later sing in 1985’s Dark Eyes – ‘life and death are memorized’. She is not only his poetic muse, but an actual gateway into the realm of spiritual transcendence that the poets Dylan has learned from most – Blake, Rimbaud and Ginsberg – have, through these tumultuous early years of his career, been leading him intro.

JOAN BAEZ

Only a few artists have attempted to cover Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands. Few have really diverged from Dylan’s own musical template. Joan Baez’s version, recorded in 1968 for her album of Dylan covers Any Day Now, is no exception. Indeed, the album was recorded in the same Nashville studio with almost the same group of backing musicians that Dylan employed on Blonde on Blonde. She uses exactly the same arrangement as Dylan. Baez has of course been a prolific interpreter of Dylan over the years. She is possessed by a voice of almost impossible purity of tone, which Dylan refers to in Chronicles as …singing straight to God… In truth, though, her record as an interpreter of Dylan – as the Any Day Now album demonstrates – is really rather patchy. Despite her great ability, she can at times lack the skills of vocal nuance. On You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere or Walkin’ Down the Line she signally fails to capture the humorous elements of the songs. But Sad Eyed Lady is – perhaps ironically – ‘made for her’. Its musical structure and – most essentially – its purity of tone are exactly suited to the crystal clear nature of her ‘angelic’ vocal style. Her version of the song is surely her finest Dylan cover, and one of the crowning achievements of her career. As she delivers the song, an added frisson is that one cannot help wondering whether she wonders if at least some of it may actually be about her.

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply