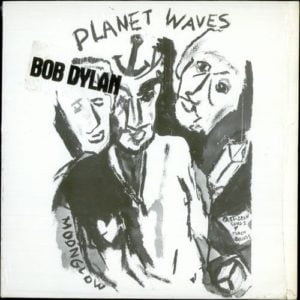

In the closing months of 1973, Bob Dylan was back in the studio recording a ‘proper’ album of new songs, his first for over three years. The resulting Planet Waves, the only studio album on which The Band backed him, was seen as somewhat underwhelming at the time and has always stood in the shadow of the following year’s stunning Blood on the Tracks. The album presents a fascinating series of contrasts. It is clearly a transitional work, dominated by songs of loving, marital bliss such as the cheerfully swinging opener On a Night like This, the straightforwardly ‘corny’ songs of devotion Hazel and You Angel You and the songs of reflective nostalgia for the days of his youth Something There is About You and Never Say Goodbye. Tough Mama, which is something of a showcase for The Band’s choppy funk, is more equivocal, implying that the relationship being depicted is more problematical. The melodic and wistful Going, Going, Gone appears to be depicting a personal inner journey, although its message is somewhat muted by rather vague imagery. On all of these songs The Band’s playing is as masterful and tasteful as ever, although Dylan’s failure to position his vocals against those of their three great singers Levon Helm, Rick Danko and Richard Manuel is perhaps surprising. In the stark piano ballad Dirge and the acoustic closer Wedding Song Dylan took us into a different realm of self-doubt. But the tracks which perhaps sum up the album’s dualistic nature best are the two recordings of the unashamedly sentimental Forever Young, one of which is taken slowly and reverently, while the faster version is presented almost as a ‘throwaway’. The song is a touching ode to one of his new born children and has become a Dylan ‘standard’, spawning countless cover versions.

On the Nashville Skyline and New Morning albums Dylan had presented himself in a radically different way to his earlier work. Gone were the epic songs full of surreal juxtapositions of language which had appeared between 1965 and 1968. He now expressed the joys of being a settled family man in an engaging and direct manner. Songs like the exquisite I Threw It All Away, the romantic Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You and his most ‘stripped down’ love song If Not For You were notable for their expression of sincere emotion. Lay Lady Lay and One More Weekend were winsome and sexy. The songs were written when Dylan was in a self imposed retreat from the highly pressurised world of constant touring and media attention. They used sentimentality and clichés playfully, in the manner of the great country songs which had inspired them

Dylan’s influence on the music of the 1960s was of course profound. He provided a definitive model for other poetic singer songwriters to follow. But during this relatively ‘fallow period’ there was a distinct sense that his contemporaries were overtaking him. Neil Young’s After the Goldrush (1970), Joni Mitchell’s Blue (1971) and Leonard Cohen’s Songs of Love and Hate (1971) were all powerful collections in which love and relationships were viewed in a far more nuanced manner than on New Morning or Planet Waves. Some singers even composed songs lamenting Dylan’s lack of engagement with ‘difficult’ issues. In Joan Baez’s heartfelt, if perhaps rather patronising, Song for Bobby (1972) she expressed her hope that he might return to writing ‘political’ or ‘protest’ material. A similar sentiment appeared in Song for Bob Dylan on David Bowie’s brilliant 1971 album Hunky Dory, in which the soon-to-be Ziggy Stardust presented a passionate appeal to Dylan to …give us back our unity/ Give us back out family/ You’re every nation’s refugee…

When Blood on the Tracks and Desire were released, Dylan answered such appeals by delivering albums whose songs had a depth, originality and perhaps most importantly – a ‘cutting edge’ of unsentimental artistic ‘truth seeking’ which were at least comparable to his great work of the mid-60s. Desire even included an authentic ‘protest song’ in the form of Hurricane. On Blood on the Tracks he invented startling new ways of dissecting relationships, presenting a series of narratives that defied the conventional laws of time and space. No other album defined the post-1960s disillusionment of the mid -70s with more eloquence. On some of the ‘symbolic’ tracks on Desire like Isis and Oh Sister he disguised his personal feelings behind a series of shifting narrative perspectives and mythical constructs. But on Sara, the frankly autobiographical last track on the album, he opened his heart to the world in by openly pleading with his wife to forgive him for his unfaithfulness. Although the critics raved at his recovery of his ‘mojo’, there is little doubt, however, that the ‘re-awakening’ of his poetic ambition and his political consciousness in these cathartic works came at an excruciatingly difficult personal cost to him. The implication seemed to be that in order for him to fully realise his potential as a poet and a musician, his own personal happiness would have to be sacrificed.

Planet Waves stands as the album which marks the transition between one phase and the other. The similarity of Wedding Song to the material on Blood on the Tracks has often been noted. The song had been hurriedly composed towards the end of the sessions. It purported to be a devotional hymn to his wife, but its tone of manic intensity revealed a kind of inner desperation that gave it more urgency and resonance than the other songs on the album. The opening line begins with a conventional sentiment: …I love you more than ever… But this is succeeded by the strange comparison …More than time and more than love… The pronouncement by a lover that his love will last ‘forever’ occurs in countless songs, but in the oxymoronic phrase ‘more than time’ Dylan abstracts this in a decidedly jarring way. The juxtaposition of this with ‘more than love’ suggests that what he is referring to as ‘love’ here is actually a kind of unhealthy obsession. Not content with this disturbing parallel, he then stretches the comparisons even further …I love you more than madness… he proclaims …more than dreams upon the sea, I love you more than life itself, you mean that much to me… His voice is harsh and bitter. The sentiment is a million miles away from the beautifully blissful vignette Never Say Goodbye which precedes it. The feeling it communicates is close to the harshly cynical denial of a song like It Ain’t Me Babe, even if the sentiments being expressed appear to be completely different.

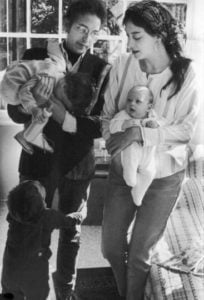

In the next three verses, all of which follow a similar musical pattern, he relates how his wife had saved him from his own demons: …Ever since you walked right in, the circle’s been complete/ I’ve said goodbye to haunted rooms and faces in the street… He describes his devotion and gratitude to her in the most extreme terms …You gave me babies one, two, three, what is more, you saved my life… We are left in no doubt that he loves his ‘babies’ but that part of him resents being trapped in the relationship. He now appears to portray himself as a ‘victim’ of this love. In the song’s most revealing line, he follows this with the monosyllabically deadpan …eye for eye and tooth for tooth, your love cuts like a knife… The line directly quotes from Leviticus 24:20:

…Breach for breach, eye for eye, tooth for tooth: as he hath caused a blemish in a man, so shall it be done to him…

The quotation, which is reiterated at several other points in the Bible, describes the ancient Hebrew belief in a law of retribution. The contrast with the line about …babies one, two, three… is quite literally vicious and, in the context of such a passionate declaration of love, rather disturbing. In another context the phrase ‘babies, one, two, three’ could be used in a song of cheerful contentment but here it almost sounds like an accusation, as if he is counting out the ‘responsibilities’ she has loaded into him. The next lines extend this sudden, uncomfortable insight into the singer’s fears: …My thoughts of you don’t ever rest, they’d kill me if I lie/ I’d sacrifice the world for you and watch my senses die… The implication seems to be that the price the singer has paid for the personal redemption of marital love and bliss is the sacrifice of his own ‘senses’ – of his own engagement with the deeper sources of his inspiration. In those years of ‘domestic bliss’, Dylan had adopted his wife Sara as his muse. In If Not For You and The Man In Me he had defined his ‘love’ as the centre of his world, the one thing in his life that gave it real spiritual meaning, without whom …winter would have no spring… But now he seems to have come to the realisation that, for him to return to producing poetic song of the kind of complexity he had achieved in the mid 60s, then his comfortable existence would have to be torn apart. This is the kind of sentiment that appears in many a country song, as the protagonist decides to take a lonesome road. But what is especially unusual about Wedding Song is that the narrator does not even pretend to be virtuous. This woman has ‘saved his life’ but now he is being decidedly cruel to her. He projects himself as an entirely unsympathetic narrator. It is thus perhaps not surprising that he abandoned the song after it was featured a number of times in the acoustic set of the 1974 tour. In the more ‘sophisticated’ Blood on the Tracks he was at least able to disguise the pain he was expressing behind a number of ‘characters’ and time-shifting scenarios. Even in Sara he romanticises the object of the song and waxes nostalgic about playing on a beach with her and his children. But here there is little doubt this is the undisguised voice of Dylan himself, spewing out his inner resentments. He is not even pretending to be a reasonable person. He presents himself as being an entirely selfish, and quite possibly misogynistic figure. Thus there is no self-censorship here, only a singer confessing his own sins with utterly disarming honesty….I love you more than ever… he confesses …and it burns me to the soul… and later, even more disturbingly …I love you more than blood…

In a later verse Dylan expands the scope of the song to answer those critics who demanded he ‘speak for them’ or (in Bowie’s words) ‘give them back their unity’. Here he claims that he is utterly incapable of fulfilling such a role …It’s never been my duty to remake the world at large… he sings …nor is it my intention to sound the battle charge… Here he seems to be quite explicitly rejecting the ‘voice of a generation’ role in favour of his devotion to his wife. Yet the song itself presents him as being ‘embattled’, as if he is fighting a war with his own conscience, and losing. Wedding Song is thus perhaps his most ‘frightening’ piece of work. Here Dylan truly faces up to the real burden of his romantic devotion to poetry. Although he has achieved true happiness and contentment in his personal life, in order to rediscover his devotion to his poetic muse, he will soon have to ‘throw it all away’.

In the final verses Dylan lapses into romantic clichés, trying to persuade his wife that he and she are bound together by fate: …You’re the other half of what I am/ You’re the missing piece… He claims that …I could never let you go no matter what goes on… But none of this is convincing, to us or to the wife being addressed. The true power of the song lies beneath the surface of the song. The listener is positioned as if they are the singer’s almost certainly wronged wife. The husband is presenting us here with a series of unconvincing self justifications, very probably for unspoken infidelities or unacceptable behaviour. Much of this is expressed through Dylan’s delivery of the song. He rushes through the verses, paying little attention to the melody, as if he is conveying a series of overwrought emotions in the midst of a furious domestic row. This is an area that few singers have ever dared to enter. The song presents a picture of a shocking emotional catharsis which prepares us for what is to come on the albums that will soon succeed Planet Waves. It demonstrates to us in no uncertain times the personal price that poets must pay in the process of digging deep inside themselves to expose their real feelings to the world, even if in doing so they may present themselves in a wholly unsympathetic way.

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply