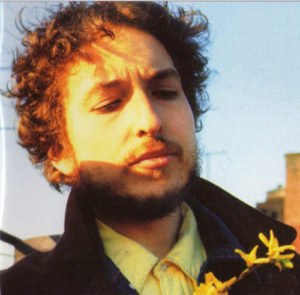

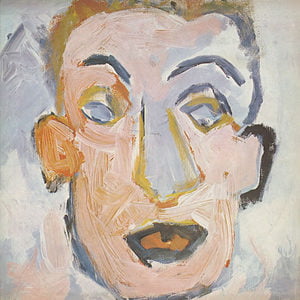

Self Portrait has long been Bob Dylan’s most controversial album. On its release in 1970 it was greeted with shock and incomprehension. Here was the great protest singer and visionary poet of his age crooning ‘corny’ country songs. On the double fold out cover there were a whole lot of shots of our man as he mulls around the farmyard, scratching his wispy beard, apparently talking to the chickens. The front cover is a child like series of paint splodges which vaguely resembles a face. This is Dylan’s own self-portrait, the first of the album’s gestures of ‘emptiness’. Having spent his career so far producing albums of original material so powerful that they rewrote the rules on writing songs, he now produces a double album with no new Dylan songs at all. Even those that are credited to him like Living the Blues and Belle Isle are actually slight adaptations of existing folk and blues tunes. In Chronicles he claims that, at the beginning of the 70s, fed up with being acclaimed as the ‘prophet’ or ‘saviour’ of the ‘Woodstock nation’, he made an album (which he does not name) merely to annoy his fans so that they would knock him off his pedestal. Whether he was ‘winding us up’ or not with that pronouncement, Self Portrait is lovingly and quite cunningly conceived. It is a self portrait using the words and music of others – a ‘picture’ of Bob Dylan derived from his absence. In many ways it sounds better today that when it first appeared. We no longer have the anxiety (and disappointment) of this being ‘the new Dylan album’. It stands alone as a landmark, not only in Dylan’s career, but in the evolution of American popular music.

The album consists of Dylan running through a selection of the kind of material he would have become familiar with in his early days in Greenwich Village – old folk, blues, country and sentimental songs, mostly delivered in Dylan’s newly patented Nashville Skyline croon, another sign of the apparent ’absence’ of the ‘folk hero’ he had become. Yet while in his early folk club days the songs would have been performed against a stark acoustic guitar, with Dylan’s harsh declamatory vocals, here the Nashville session musicians help create a smoothly relaxed groove. Self Portrait is more than the sum of its parts. It is simultaneously a conceptual experiment, a joke and a serious attempt by Dylan to ‘get back to his roots’. What really distinguishes the album, however, is its sequencing – providing us with a tapestry of American music which flows together with its own internal logic. The album begins with one of the strangest entries in Dylan’s catalogue, as the three backing singers trill the lines …All the tired horses in the sun/ How’m I supposed to get any riding done? … over and over again, against sweeping strings. The singers pronounce ‘riding’ so that it could easily be mistaken for ‘writing’. Dylan himself is absent from the track. Here again his absence is foregrounded.

The suite of songs that follows presents a cornucopia of American music, which begins and ends with two laid back versions of Leadbelly’s slow and slyly lustful Alberta. In between Dylan plays with his audience’s perceptions, presenting himself as an out and crooner on a bizarre version of the standard Blue Moon which ends in a screechy violin solo and a fully committed take on the maudlin country standard I Forgot More than You’ll Ever Know. ‘How far can I push this?’ Dylan must surely have been thinking. Later he will give us similarly ‘sweet’ takes on two Everly Brothers songs, the prisoner’s lamentTake a Message to Mary and the gorgeous love song Let It Be Me. Much of the album was overdubbed with strings – anathema to many Dylan fans who associated orchestration with the old sentimental styles which Dylan himself appeared to have contributed so much to destroying. Yet the use of strings ties the album together, giving it a symphonic sweep. There are two versions of the rather gleeful murder ballad In Search of Little Sadie – one fast, the other even faster. There is a lovely rendition of Gordon Lightfoot’s Early Morning Rain which Dylan croons in a deep respectful baritone. The traditional gold rush tune Days of 49 sounds, in contrast, like ‘old Dylan’ and could almost have appeared on his first album. Self Portrait thus presents us with different versions of the singer. He is a barrelhouse piano player on the instrumental Woogie Boogie; a light, jazzy blues crooner on It Hurts Me Too and Living the Blues and the leader of a cheery folk ensemble on Paul Clayton’s Gotta Travel On. The album’s outstanding track is Dylan’s fully committed and nuanced rendition of Copper Kettle, the old bootleggers song in which the narrator luxuriates in being able to …lay there by the juniper/ While the moon is bright/ Watch them jugs a-fillin’ in the pale moon light… Dylan’s powerful vocal performance sums up the mood of the whole album. The old bootlegger delights in how easy it is to produce his ‘moonshine’ gin and whisky. He lies back, contentedly inebriated, caring not about what effect the distilling of this potent brew may have on him or those who will receive it. It is as if Dylan himself is ‘laying back’, chuckling at us all. Surely, he seems to be teasing us, he has earned the right now to ‘take it easy’.

One of the most controversial aspects of Self Portrait was the use of string arrangements. Prior to this Dylan – with his famous commitment to spontaneity – had mostly been recorded live in the studio, eschewing overdubs. But here he allows producer Bob Johnston to overlay many of the tracks with strings. In 2016, when the Bootleg Series release Another Self Portrait came out – ironically, to great critical acclaim – a number of the songs from the album were presented in a more recognisably ‘Dylanesque’ manner, with the overdubs removed. The ‘stripped down’ version of Copper Kettle demonstrates Dylan’s vocal prowess very effectively, but there is still something ‘missing’ here. In fact the effect of the orchestration is to bind the album together, making it sound more like a continuous, unified piece of music – an ‘American symphony’ which in some ways recalls the work of the acclaimed American classical composer Aaron Copland who based his compositions on traditional folk tunes. Extracts from Copland’s Appalachian Spring were regularly played before Dylan’s live shows for several years in the 2000s.

Self Portrait also includes several tracks from the Isle of Wight show from 1969 in which Dylan played a unique set of ‘countrified’ arrangements of his songs. Here the heavily stylised take on Like a Rolling Stone presents it as pleasant ballad with its original rage stripped away. She Belongs to Me is heavily and rather quirkily rearranged and Quinn the Eskimo is a rollicking take on this surreal nonsense rhyme from The Basement Tapes. The other track from the show, Minstrel Boy (another song originally from The Basement Tapes) is the only ‘original’ previously unheard Dylan song on the album, which centres on the plaintive: …Who’s gonna throw that minstrel boy a coin/ Who’s gonna let it roll… Who’s gonna let it down easy to save his soul…. Dylan himself is, of course, the ‘minstrel boy’ – just a ‘poor boy’ singing for his supper rather than some great counter cultural hero. Ironically, this unique performance of the song is given to the huge crowd that have assembled to see Dylan at one of the first major rock festivals. What these tracks again emphasise is the conceptual ‘absence’ of the ‘recognisable’ Dylan.

Other songs on Self Portrait deliver this antithetical presentation of himself in different ways. Take Me as I Am (Or Let Me Go), originally a hit for Jimmy Dickens in 1954, is given the full Nashville treatment with syrupy steel guitar in full effect. The song is a rejection of a lover who apparently wishes to ‘mould’ and ‘reshape’ the narrator – a sentimental version, perhaps, of It Ain’t Me, Babe. Dylan delivers it in a histrionic croon, challenging the audience to accept this ‘hollow’ version of himself. He turns the the ‘corny’ lyrics into a challenge to his listeners. Here is a singer, he seems to be telling us, not a prophet – they can either accept him or not. Another ‘conceptual’ experiment is the rather weird version of Paul Simon’s brilliant opus of personal struggle The Boxer. Both ‘Dylan’ voices – that of the old, abrasive folk singer and that of the newly smooth crooner – feature, with one double tracked over the other. Here are two ‘Dylans’ – but we do not know which one is ‘real’. And as they strain to harmonise, Simon’s words …I am leaving, I am leaving, but the fighter still remains… reminds us that the ‘old Dylan’ may soon return.

So cast away your Greil Marcus reviews, your ‘worst album of all time’ rankings. Kick back and drown in Dylan’s symphony of America. A musical ‘self portrait’ constructed of other people’s words and music. Take a deep breath. Let it wash over you. It’ll give you more gold than your apron can hold….

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply