BOB DYLAN’S THE LEVEE’S GONNA BREAK

…I look in your eyes, I see nobody other than me,

I see all that I am and all I hope to be…

The secret language of the blues has always enthralled Bob Dylan. From his earliest days as a performer he has been irresistibly attracted to its sly, lascivious poetic sensibility, its subtle use of imagery and nuance, the codes and sub-codes and complex patterns of reference within its corpus. His ambition has always been to inhabit the mental condition of the great blues singers, to …carry myself like Big Joe Williams… as he once put it, to locate the body of his own work within the emotional world that the greatest blues singers of the form’s classic mid twentieth century period (particularly between the 1920s and the 1950s) had constructed. As a boy in the early 1950s, his ear craned to the radio, those singers must have seemed to him to speak from a mysterious, dangerous, yet often hilarious, place where life was being experienced to the full, in all its horror and ecstasy. Yet unlike the blues singers he has always eulogised with such awe Dylan was not born into poverty in the sweaty Mississippi Delta but in the cold, windy North Country at the opposite northern end of Highway 61. And unlike them, he was also highly (self) educated in the whole poetic tradition of Western culture. Perhaps his most original stylistic trait – as both a musician and a writer – is his often playful fusing of the sensibility of the blues with literary techniques and concepts. We think of lines like …Need a dump truck baby to/unload my head… Mona Lisa musta had the highway blues… I seen pretty people disappear like smoke… as especially ‘Dylanesque’, because of the way he seamlessly integrates symbolic imagery with blues vernacular.

As Dylan has grown older, he has re-immersed himself in blues imagery and attitude. World Gone Wrong, his immaculately executed 1993 album of covers of songs by the Mississippi Sheiks, Blind Willie McTell and others, preceded his wholesale adoption of blues form on much of Time Out Of Mind, Love and Theft and Modern Times. On these albums he constructs many of his songs from scattered pieces of blues imagery, reassembling them in a kind of collage in a way that might well be called self-referentially ‘post modern’. Yet in doing so he reveals the way in which the blues of the classic period was ‘post modern’ in its own way, well before the verbose French intellectuals of the 60s and 70s strove to define postmodernism as our culture’s current condition. During the last decade Dylan has, in fact (in his own guardedly ambiguous, stoically po-faced way) identified himself more and more with the sensibilities of that period, exploring the ‘sentimental’ tradition of mainstream songwriting of the time in pieces like Make You Feel My Love, Moonlight, Bye and Bye and Beyond The Horizon. As part of this process he has gradually abandoned his disheveled jeans-and-stubble look in his live performances in favour of elaborately stylized and deliberately archaic suits. While other rock stars of his age (like Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger) try to present themselves as eternally youthful, Dylan has appeared to glory in ‘being old’. He even frequently sports a very ‘1940s’ style pencil-thin moustache, in the manner of Errol Flynn. It is as if he is quite deliberately positioning himself in the pre-1960s world, a stance which helps to give his latter-day work great ironic resonance. The blues singers of the classic period were not – as liberal folkies used to like to imagine – tortured souls dedicated to a purist musical ethos in the service of some quasi-political message. They were primarily entertainers, whose job it was to make people smile and to get them dancing on a Saturday night after a week’s hard graft. Most blues singers thus mixed in the blues with other contemporary song forms. It is this mixture which the modern Dylan – in his albums and his inspirational radio show – celebrates.

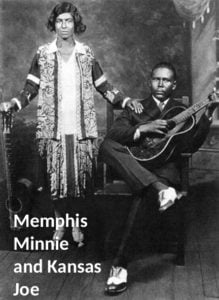

The Levee’s Gonna Break is – like a number of Dylan’s other recent songs – a dance tune, characterised by an insistent, repetitive, yet understated rhythm. It’s a showcase for the tasteful ensemble playing of Dylan’s current, highly unshowy, dark-suited band. In the context of Modern Times it provides some uplifting moments between the philosophical resignation of Nettie Moore and the apocalyptic brooding of Ain’t Talkin’. Despite its tone of ‘flirting with disaster’ it’s basically a cheerful work out, often used very effectively in live performance to build up the tempo of the shows. The song is, like Rolling and Tumbling and Someday Baby, an adaptation of a well known blues classic, Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe McCoy’s When The Levee Breaks (1929), which in 1971 was developed into the Led Zeppelin song of the same name. The Zeppelin version, with its iconic and much-sampled ‘heavy’ drum sound, is undoubtedly a potent evocation of a kind of dread the singer feels at the power of nature. But Dylan’s take on the song- though it uses few of the original lyrics – returns to the more equivocal tone of the duo’s recording. Released two years after the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which caused huge disruption among the black community in the state of Mississippi, When The Levee Breaks was one of a number of songs related to this event. Half a million homes were destroyed and the flood covered an area of 15,000 miles. The flood’s effects contributed greatly to the mass migrations of black people to Chicago and other Northern cities, which were to be further intensified by the Wall Street Crash and the onset of the depression a couple of years later. Yet the plight of such huge numbers of poor black people met with much indifference from the government and the media of the day. Despite this, singer Kansas Joe approaches this great disaster with apparent stoical indifference. The pretty, deft guitar picking by Joe and Memphis Minnie gives the track a lightness of tone. And though Joe tells us he’s …worked on the levee, mama both night and day… and claims to have ...nobody to tell my troubles to… it’s almost as if the flood is merely a kind of backdrop for his complaints about the ‘woman trouble’ that he keeps alluding to. Rather than being angry, he seems merely resigned to his fate. It’s as if the great effort he’s put it to prevent the dam bursting is more important as a symbol of the impossibility of him keeping his woman.

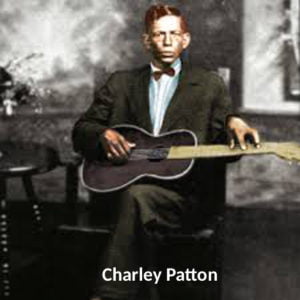

Dylan’s version of the song has inevitably been seen as a comment on the modern equivalent of the 1927 flood, the Hurricane Katrina disaster of 2005, when again the plight of huge numbers of displaced black people met with great official indifference and neglect. Yet though there are a few passing (if ambiguous) references to such a calamity, particularly in lines such as …some people on the road carrying everything that they own… The Levee’s Gonna Break can hardly be called a ‘protest’ about the subject (though many have fondly imagined it to be so). As with the original song, the great flood alluded to (and the ominous ongoing threat of an even greater one) is merely a kind of backdrop to the singer’s more pressing concerns – his failure to keep or satisfy his woman and his concern with personal salvation. Dylan’s lyrics reference a number of other songs – in particular Carl Perkins’ Put Your Cat Clothes On (1956) and Charlie Jackson’s Butter and Egg Man Blues (1925). But the song also powerfully echoes Dylan’s own Down In The Flood (also known as Crash On The Levee) from The Basement Tapes (1967), a song which has featured widely in his Never Ending Tour live shows. The ‘crash’ in that song may well be an allusion to Dylan’s own semi-mythical motorbike crash which ended his ‘amphetamine clown’ period of the mid-60s. Certainly it is a song of rejection, for a lover who’ll have to …find yourself another best friend somehow… (which, by extension, might well be applied to the singer’s own audience). Yet it also dramatises a kind of spiritual struggle, firmly placing the responsibility for an individual’s chances of salvation on their own head: …it’s sugar for sugar, salt for salt/If you go down in the flood it’s gonna be your fault… In the blues, and in much of Dylan’s work, the imagery of flooding often implies a kind of judgement – divine or otherwise – on the human condition. A ‘hard rain’ will come to wash away sin and lies, as it does in the great biblical flood. Everybody’s making love, or else expecting rain. In two of his most powerful recent songs Dylan again evokes flood imagery. In Trying To Get To Heaven from Time Out Of Mind (1997), before embarking on a journey down river to New Orleans, he declares he’s …wading through the high muddy water/With the heat rising in my eyes… And in Love and Theft’s High Water (itself based on a Charley Patton song about the great New Orleans flood of 1927, to which it makes several direct allusions, the flood becomes generalised as an index of moral and corruption and religious hypocrisy.

In contrast, the voice of The Levee’s Gonna Break appears relatively nonchalant. Like Kansas Joe, Dylan maintains a tone of apparent indifference. His seems to have several concerns – spiritual, social and personal – all of which he refers to in a rather offhand way. At several points he hints at a kind of (presumably failed) spiritual quest. In the first verse we hear that …everybody sayin’ this is a day only the Lord could make… suggesting the flood has been the result of divine intervention. We hear the narrator tell us that …I got to the river and I threw my clothes away… suggesting some attempt at baptism or personal spiritual ‘cleansing’. Later there is the somewhat equivocal promise that …riches and salvation can be waiting behind the next bend in the road… and the oddly millenialist ….Few more years of hard work, then there’ll be a 1,000 years of happiness… But the singer never sounds convinced that such ‘salvation’ is at hand. If the flood he refers to really is some divinely inspired apocalypse, it seems that he’s hedging his bets on the results of Judgement Day. At the same time there’s a kind of social conscience at work – apparent resentment at the unnamed forces of authority who will … strip you of all they can take… as well as the reference to displaced homeless masses who …don’t know which road to take… The narrator merely describes the situation rather than putting any political point of view forward.

The singer’s main concerns seem to be personal. A few verses in we get the sarcastic, resentful ...I picked you up from the gutter and this is the thanks I get… followed by the supremely laconic …You say you want me to quit ya, I told ya, ‘No, not just yet.’… In the great blues tradition, the singer’s political and spiritual concerns seem to be a kind of smokescreen for anxieties about his personal sexual life. There are veiled hints of his lover’s somewhat overpowering sexuality: …I woke up this morning, butter and eggs in my bed/I ain’t got enough room to even raise my head… confessions of devotion: … When I’m with you, I forget I was ever blue/Without you there’s no meaning in anything I do… and a final plea to his lover not to leave him. But there’s always a sense that the woman is far stronger than him and that he’s in fact being controlled by her: …I tried to get you to love me, but I won’t repeat that mistake… Perhaps the most revealing lines, though, occur in the middle of the song …I look in your eyes, I see nobody other than me/ I see all that I am and all I hope to be… This is a quintessentially Dylanesque paradox, reminiscent of earlier songs like It Ain’t Me Babe and Just Like A Woman where the identity of the ‘lover’ in the song is revealed to be partly an aspect of the narrator himself. Indeed the lines directly recall those from Denise, an unreleased cut from the Another Side sessions (1964) where the singer concludes: …I’m looking deep in your eyes, babe, and all I can see is myself… Although the image in The Levee’s Gonna Break describes the purely physical effect of looking into another’s eyes and seeing your own reflection, the rather philosophical emphasis of the following line creates an ambiguous suggestion that in addressing his elusive lover, the narrator is in fact (as with the almost intangible figure of ‘Louise’ in Visions of Johanna) using her as a ‘mirror’ for the imperfections of his own soul.

The original version of the song had used the threat of the breaking down of the levees as a metaphor for the frustration the singer feels at the way his lover has treated him. Dylan retains this dynamic in his version but also extends it into a kind of self-examination. Against a backdrop of apocalyptic chaos in the world outside he reflects on his own inner imperfections. It’s as if he’s sitting in a darkened room, casually flicking through the news channels, picking up snippets of information. But he’s not really concentrating on what he sees in front of him. He’s just thinking about himself. In that way the song very much reflects the modern condition – the indifference with which we accept great natural disasters. Yet despite the casualness of the narrator’s tone and the elevating lightness of the music that accompanies the voice, the constant repetitious pitter-patter of the rain that continues to fall may yet threaten us all. As the planet’s icecaps melt and floods of biblical proportions threaten to gather, we sit alone like Dylan’s narrator, preoccupied with other matters. The condition, perhaps, of our Modern Times. Here we sit so patiently, waiting to find out what price we will have to pay for our indifference. The final lines of the song add up to a portentous warning: …Some people are still sleeping… Dylan drawls, as if unconcerned …some people are wide awake…

Perhaps it’s time, then, that we woke up.

A different version of this text appears in DETERMINED TO STAND: THE REINVENTION OF BOB DYLAN

———————————————————————————————–

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply