BOB DYLAN: MOST OF THE TIME

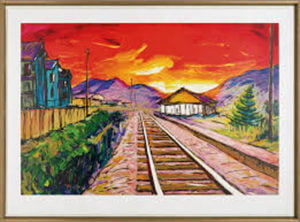

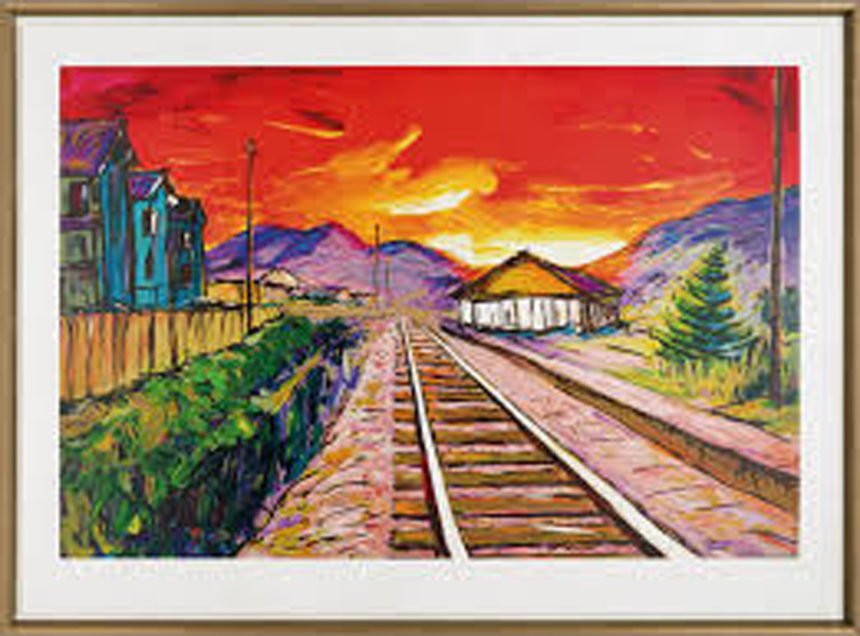

The ‘Drawn Blank Series’, the exhibition of Bob Dylan’s paintings currently showing at Edinburgh’s City Art Centre, provides a valuable insight into Dylan’s creative and imaginative processes. The paintings are based on a series of drawings Dylan completed in the late 80s and early 90s. In what the exhibition catalogue describes as ‘an intense burst of creativity in 2007’ Dylan began applying paint to blown-up versions of these black and white, impressionistic images of scenes he’d experienced or imagined in the early stages of his Never Ending Tour. Many of the drawings (like ‘Train Tracks’ above) are presented in their illuminated form in a series of different versions. The effect of the addition of colour is akin to his ‘going electric’ with his music, illuminating the harsh outlines he has drawn and creating a means by which his basic template can be the subject of endless variation. This is a similar process to the one being enacted on Tell Tale Signs, wherein we get an intimate glimpse into the evolution of Dylan’s songs. Tell Tale Signs makes the ‘secret’ that Dylan bootleg collectors have pursued from the legendary Great White Wonder onwards public – namely, that there really is no definitive ‘final’ version of any Dylan song. Sometimes what are arguably the most memorable versions of Dylan’s songs may only exist on the ‘cutting room floor’ of his recording studio. Just as the three versions of Mississippi featured here demonstrate three different moods and types of emphasis, so the three versions of Train Tracks take us from blazing desert sunshine to the vibrancy of spring to the darkening storms of late summer.

The version of Most Of The Time which follows Mississippi on Disc One of Tell Tale Signs is perhaps the album’s most startling surprise variation on one of his existing ‘templates’. A solo guitar and harmonica take with a style highly reminiscent of the early Blood On The Tracks sessions, it sounds utterly different to the familiar Oh Mercy version, with its swampy, spooky background ambience deriving from Daniel Lanois’ trademark production traits. The version of Disc Three of Tell Tale Signs is quite close to the Oh Mercy version, though it sounds a little less ‘produced’. The lyrics are identical to the earlier-released version though the instrumentation is more muted, and more emphasis is placed on the vocal. Most Of The Time is an exercise in irony and rueful self-deprecation from an artist engaged in the severe self-analysis that permeates the album (which could well have taken its title from the self-explicit song What Good Am I? In each verse the singer enunciates a long list of his own positive traits, which the repetition of the title line at the end of each verse immediately deflates. We soon realise that the singer has been deserted by his lover and is conducting a supposedly defiant internal dialogue. … I don’t even notice she’s gone… he tells us. … I don’t think about her… and, more graphically, …I don’t even remember what her lips felt like on mine… In the original version Dylan sounds tight lipped, with a clear edge of bitterness. He delivers the lines sardonically, barely letting those constrained emotions out. The performance is a kind of dark study, with the narrator apparently drowning in self-delusion. Lanois uses muted bass and drum patterns with swirling, heavily treated guitar sounds to emphasise the singer’s predicament. The overall effect is somewhat dreamlike, as if the narrator is both inside and outside the action. The prevailing mood is a kind of reflective gloom. Written at a time when Dylan was struggling for inspiration (on his last album Down In The Groove he had produced no new lyrics whatever), the song displays the mood of an artist struggling with a muse whom he fears may well have deserted him ‘most of the time’. The ease in creativity he once had has gone. He is bent in contemplation, hoping for the rare moments of clarity to come.

The ‘new’ version on Disc One has a very different ambience. In spirit if not in form, that same ambience is often found in the work of blues singers like Sleepy John Estes, Blind Willie Johnson and the Mississippi Sheiks, who describe the hard times they experience with a light touch which lifts the listener onto a different plane. In what was presumably a ‘demo’ version Dylan presented to Lanois before the song was rerecorded and treated, this version has the spirited intensity of Dylan’s best solo work. The breezy harmonica in between the verses adds to the tone of optimistic resilience which makes the song a description of a defiant struggle rather than a glum wallow in despair. So when Dylan sings … I can handle whatever I stumble upon.. we really believe him. In this version the self-reassuring doubt in the lyric works against the singer’s tone. It is a similar effect to the Blood On The Tracks songs like You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go and Buckets Of Rain, taking us on a kind of emotional roller coaster which we somehow feel we may fall off at any moment. The singer maintains a delicate balance between prevailing optimism and underlying despair.

As with most of the Oh Mercy material the language is spare, terse, lacking in obviously ‘poetic’ imagery. The major lyrical difference from the recorded version comes in the second verse, where instead of the resignation of …it’s well understood… I wouldn’t change it if I could… we get the more pithy …I’m cool underneath… I can keep it right between my teeth… (a neat reference, perhaps, to the harmonica which does not feature on the Oh Mercy version. The self-analytical heart of the song comes in the third verse, which begins with the skewed self mockery of …most of the time/my head is on straight… (after which the retort of …I’m strong enough not to hate…is a little disappointing). In the Oh Mercy version the verse contains the song’s most remarkably ‘twisted’ couplet …I don’t build up illusion ‘till it makes me sick/ I ain’t afraid of confusion no matter how thick… Here we get the far lighter and more positive…I got enough faith and I got enough strength/I keep it all away, way beyond arm’s length…

The fourth verse is a kind of bridge, varying the rhyme scheme and striking a note of reticence. The singer begins to express doubts about whether his encounter with the unnamed lover even took place: …Most of the time/I can’t even be sure/If she was ever with me/Or if I was with her… It is a sentiment that will be echoed again in Red River Shore, which takes on the same themes in a deeper, more tragic manner. Most Of The Time is an almost ‘textbook’ example of one of Dylan’s ‘anti-love’ songs, a tradition that goes back to Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right , It Ain’t Me, Babe and Mama You Been On My Mind. Here for a moment the singer questions even the validity of his own feelings. In the final verse he admits to being …halfways content…. before building up his bravado in the final verse: …I don’t cheat on myself /I don’t run and hide/ Hide from the feelings/ That are buried inside / I don’t compromise or pretend… And finally, with apparently complete defiance: … I don’t even care if I ever see her again… Of course, by now we hardly believe him and the final equivocation of the last repetition of the title phrase demolishes all this huffing and puffing very neatly.

Most Of The Time is a song of psychological self-examination. As many great blues songs do, it adopts the stance of a jilted lover to explorer deeper inner themes. The singer appears to be reassuring his audience but we soon realise that he is only reassuring himself. The real subject of the song – as of so much of Oh Mercy – is Dylan’s own inner spiritual turmoil, his struggles with what in Street Legal’s Where Are You Tonight he called …my twin/the enemy within… To Dylan, spirituality and creative inspiration are inseparable. Only by truly facing up to this ‘enemy within’ – manifested as a lack of inspiration – can he overcome it.

The unexpected revelation of the Disc One performance of the song (it was unknown on the bootleg circuit before the album’s release) also raises the question as to whether Dylan was wise to accept the ‘production values’ foisted upon him by Lanois in Oh Mercy. In Chronicles Part One Dylan devotes a whole chapter to the recording of the album, relating how previous to making the album he had not written for some time, but then found himself pouring out the songs that later appeared on it. He seems to arrived at Lanois’ home studio in New Orleans uncertain whether the songs he had written were really worthwhile or not. Chronicles also hints at the tensions between artist and producer over the type of sound they were striving for. It seems that at the time Dylan felt so lacking in confidence that he felt he needed ‘producing’ (He claims that Bono had recommended Lanois to him one night when they were demolishing ‘a crate of Guinness)’. Yet the strength and originality and the brave self-searching nature of the Oh Mercy songs shows that Dylan’s fears of his own creative death were totally unfounded. Dylan brought back Lanois for Time Out Of Mind in 1997 (though on the latter album Lanois’ trademark production sound is considerably less pronounced) but all subsequent recordings he has produced himself (under the mischievous pseudonymn of ‘Jack Frost’). Much of Tell Tale Signs presents ‘de-Lanoisised’ versions of the material from these two albums, and it is tantalising to imagine what Oh Mercy would have sounded like if Dylan had recorded it as a solo acoustic album (as he later did with the ‘roots’ albums Good As I Been To You and World Gone Wrong). Here, on what may well have been the first recorded version of the song, he nails its tone of wavering emotions perfectly, with a masterful example of what his great supporter Allen Ginsberg referred to as his ‘breath control’.

A different version of this text appears in DETERMINED TO STAND: THE REINVENTION OF BOB DYLAN

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply