BOB DYLAN: DIGNITY

…Soul of a nation is under the knife…

Dignity, like Series Of Dreams and God Knows, was originally written and recorded for Oh Mercy. It was eventually released in remixed form as a single some five years later and also appeared on the MTV Unplugged album in 1996. Tell Tale Signs features two radically different versions of the song from the Oh Mercy sessions. The song has also been performed live on many occasions, with a number of lyrical variations. In Chronicles Volume One Dylan describes how all the attempts at recording the song for Oh Mercy, including an evening spent with a local Cajun band, ended in apparent failure. But by looking at the different versions of the song we can trace a different story. What the various versions of the song have in common is their wild juxtaposition of images. In searching for such an indistinct inner quality we are taken on a mad ride through another ‘series of dreams’. The singer is a kind of Don Quixote figure, rushing madly at disappearing windmills and inviting us to ride, like Sancho Panza, at his side.

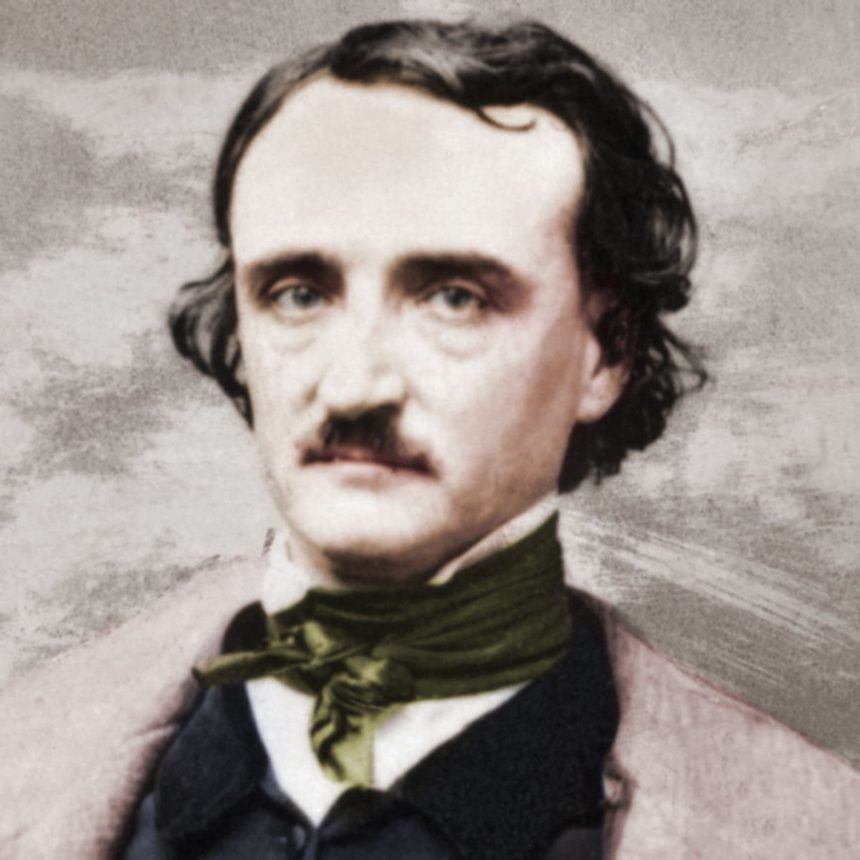

Speaking of knights on quests, the first released version of the song brings to mind Edgar Allan Poe’s poem El Dorado, itself constructed like a song, and written very much in the clipped, nuanced style Dylan adopts on Oh Mercy. One can easily imagine Dylan himself singing these words in his nasal style, stretching out the syllables for effect, and with Lanois’ distinctive atmospherics in the background:

EDGAR ALLAN POE

Gaily bedight,

A gallant knight,

In sunshine and in shadow,

Had journeyed long,

Singing a song,

In search of Eldorado.

But he grew old

This knight so bold

And o’er his heart a shadow

Fell as he found

No spot of ground

That looked like Eldorado.

And, as his strength

Failed him at length,

He met a pilgrim shadow

“Shadow,” said he,

“Where can it be

This land of Eldorado?”

“Over the Mountains

Of the Moon,

Down the Valley of the Shadow,

Ride, boldly ride,”

The shade replied

“If you seek for Eldorado!”

The point of the poem is that – as with the search for the Holy Grail – it is the quest itself which is the important thing. Indeed, the quest is Eldorado. So it is, perhaps, with the quest for Dignity. That’s ‘Dignity’ with a capital ‘D’. The poetic technique utilised here – that of personification – is one which Dylan has used very rarely. In the originally released version we are presented with a parade of archetypal characters, identified as ‘fat man’, ‘thin man’, ‘hollow man’ ‘wise man’, ‘blind man’ ‘sick man’ and finally ‘Englishman’, all of whom are presented in the present tense engaged in various activities connected with finding some kind of meaning in their lives. These moments of potential revelation pass by as if we are looking out of a moving car window as Dylan follows the jaunty tune. There is little emotional involvement in his voice. This is a picaresque travelogue. We go to ‘the land of the midnight sun’ (Finland, perhaps?), we meet someone called Mary Lou who … Said she could get killed if she told me what she knew/About Dignity… and later the mysterious’ Prince Philip at the home of the blues’, who appears to be some kind of ‘super grass’ who … Said he’d give me information if his name wasn’t used/He wanted money up front, said he was abused/By dignity…. Dignity, it seems, is a secret, an unknowable condition which you will search ‘every masterpiece of literature’ for in vain. Dignity is an enigmatic and playful song, yet it has a personal resonance. Perhaps its most telling lines come in the penultimate verse: … Someone showed me a picture and I just laughed/ Dignity never been photographed… a rather cynical aside from one who has been photographed so many times since the start of his career and perhaps a veiled comment on the difficulty of maintaining artistic credibility when one is a famous celebrity. The narrator never finds what he is looking for. What he seeks is a chimera, an Eldorado without a name.

The Oh Mercy outtake version of Dignity which appears on Disc Two of Tell Tale Signs is heavily rewritten, its music reduced to a simple repetitive guitar riff. Dylan still plays the role of the confused ingénue. The characters have been jumbled up. ‘Prince Philip’ now meets ‘Mary Lou’. A conversation between ‘Don Juan’ and ‘Don Miguel’ outside the Gates of Hell is recounted. Here Dignity is quite explicitly feminised. She is …a woman that knows/ a woman unspoiled/ a woman that’s light/ a woman that bleeds… The imagery is even more bizarre and confusing than in the released version. There are a few remarkable poetic snippets, especially in the evocative lines …Cities in a mess of jackhammer beats/ Buses roll by with burned-out seats/ A child’s eyes look through the creeping streets/For dignity… But despite the dark undertones of this, Dylan still delivers the lines blithely. Towards the end it’s made quite explicit that ….Dignity got no starting-point/ No beginning, no middle, no end… The final verse leaves us stranded with no definite answers …Looking at a glass that’s half-filled/ Looking at a dream that’s just been killed…

Perhaps the reason Dylan never originally released this song is that the  appropriate combination of words and music for the song proved as elusive as the search for ‘Dignity’ itself. The search for ‘Dignity’ is in many ways the quest which Dylan set himself in the 1990s. He came to fame as a precocious young man, howling bittersweet poems at the world. Later he sought solace in love, in religion, and in what his ubiquitous concert intro calls …a haze of substance abuse… By the late 1980s his loss of ‘Dignity’ was most eloquently demonstrated by his performance as the burnt out rock star Billy Parker in Hearts of Fire, a dreadful mess of a movie featuring two new original Dylan compositions, Had A Dream About You Baby and Night After Night, which were almost excruciatingly banal. He was playing a part, right? Well, maybe… It was not long after Hearts of Fire that, as Dylan later claimed, he experienced his ‘Determined to Stand’ epiphany which led to the Never Ending Tour and his eventual transformation into his current ‘wicked old man’ persona. The dilemma he was facing in the late 80s was how to reinvent himself, how to remake his art, as a much older person, in late middle age. Achieving the kind of ‘Dignity’ which was so clearly missing in his embarrassing attempts at 80s production values on Empire Burlesque and on the vacuous songs like Knocked out Loaded’s Got My Mind Made Up or Down In The Groove’s Ugliest Girl In The World became an absolute necessity. And so, on Oh Mercy, he began this process. Yet both the eventually released version and the version of Disc Two of Tell Tale Signs suggest a lack of resolution and of real emotional engagement. ‘Dignity’ is occasionally glimpsed, but never found. Of course, that in a way is the point of the song. Yet there is a sense in which Dylan never quite seems to take the song seriously. In live performances in 1985 and 2000 he shuffles the verses around as if they are interchangeable, which perhaps they are. The song is mildly engaging, a kind of clever intellectual game, but it is rarely revelatory or in any way moving.

appropriate combination of words and music for the song proved as elusive as the search for ‘Dignity’ itself. The search for ‘Dignity’ is in many ways the quest which Dylan set himself in the 1990s. He came to fame as a precocious young man, howling bittersweet poems at the world. Later he sought solace in love, in religion, and in what his ubiquitous concert intro calls …a haze of substance abuse… By the late 1980s his loss of ‘Dignity’ was most eloquently demonstrated by his performance as the burnt out rock star Billy Parker in Hearts of Fire, a dreadful mess of a movie featuring two new original Dylan compositions, Had A Dream About You Baby and Night After Night, which were almost excruciatingly banal. He was playing a part, right? Well, maybe… It was not long after Hearts of Fire that, as Dylan later claimed, he experienced his ‘Determined to Stand’ epiphany which led to the Never Ending Tour and his eventual transformation into his current ‘wicked old man’ persona. The dilemma he was facing in the late 80s was how to reinvent himself, how to remake his art, as a much older person, in late middle age. Achieving the kind of ‘Dignity’ which was so clearly missing in his embarrassing attempts at 80s production values on Empire Burlesque and on the vacuous songs like Knocked out Loaded’s Got My Mind Made Up or Down In The Groove’s Ugliest Girl In The World became an absolute necessity. And so, on Oh Mercy, he began this process. Yet both the eventually released version and the version of Disc Two of Tell Tale Signs suggest a lack of resolution and of real emotional engagement. ‘Dignity’ is occasionally glimpsed, but never found. Of course, that in a way is the point of the song. Yet there is a sense in which Dylan never quite seems to take the song seriously. In live performances in 1985 and 2000 he shuffles the verses around as if they are interchangeable, which perhaps they are. The song is mildly engaging, a kind of clever intellectual game, but it is rarely revelatory or in any way moving.

The ‘piano demo’ version of Dignity on Disc One of Tell Tale Signs is, however, a very different matter. As shockingly stark as the versions of Mississippi and Most Of The Time which precede it, here the song is stripped down to its essence. Whereas in the other versions it seems to meander happily, here it is sharply focused and performed with a raw, tortured emotional edge. The bouncy riff is absent, replaced by Dylan’s stabbing solo piano which perfectly complements the tone of the performance. Here the song has a clear structure, rising to a crescendo of bitter irony. The journey being depicted is scary, intense – a voyage into inner pain in search of inspiration, a graphic description of the struggle of the artist’s creative soul to come into being. Dylan’s enunciation of the lyrics is precisely honed – he is fully engaged with the pain he is feeling. Here his vocal performance, with its strange dips and hoarse expression, prefigures the ‘new voice’ he would begin to adopt on the Good As I Been To You and World Gone Wrong ‘return to roots’ albums of the mid-90s. This version is, just like its predecessors on the album’s track list, ‘merely’ a first take, a ‘demo’ version of the song. But it is here, rather than on subsequent versions in the studio or live, that he really nails the song.

And he really nails it. Here there is a real effort to place discordant emphasis on certain words. In the first verse his voice jerks and falls at the mention of the three ‘men’: ‘fat’, ‘thin’ and ‘hollow’. The piano has an eerie, gospelly quality which is matched by the extraordinary vocal. …Wise man looking in a blade of grass’ … he intones deeply. Then before the next line there is an odd semi-stutter …Er… young man looking in the shadows that pass… as if he is ‘testifying’, letting out guttural shrieks involuntarily. The first five verses follow the lines of the released version, but it is in the later (presumably later rejected) verses that we really get to the meat of the song. The ‘stranger’ in verse six … stares down into the light/From a platinum window in the Mexican night… Suddenly the song has a location, somewhere hot and sticky and drenched in Catholic guilt. The stranger is engaged in … Searching every blood sucking thing inside/ for dignity… These lines give the descent into the land ‘where the vultures feed’ far more resonance than when the same lines appear in the ‘original’ version. This search for Dignity is no search for Eldorado. The singer has no hope of paradise. He has opened the gates of hell. Dylan’s acidic pronounciation of the killer line in the last verse …. Soul of a nation is under the knife… universalises the singer’s predicament. We then get another piece of personification as the Grim Reaper himself appears … Death is standing in the doorway of life… The irony is grim and unmistakeable. There is a heavy, violent threat hanging in the air, a sense of extreme existential despair, now vividly contrasted in the final lines with domestic violence … In the next room a man fighting with his wife/ over Dignity… Then the song abruptly peters out, as if the singer’s sustained drawn breath (which began with his stuttering testifying in verse two) has finally evaporated. The Dignity he has found is a cruel illusion and its exposure has opened up a spiritual void. Thus this version of Dignity dramatises the pain involved in the loss of religious faith which Oh Mercy songs like What Good Am I?, Ring Them Bells and What Was It You Wanted imply, no more so than in the despairing lines which here are thrown into the sharpest relief … Heard the tongues of angels and the tongues of men/ It all sounded no different to me…

The mood of this early, supposedly ‘unfinished’ yet devastating powerful version of Dignity is less reminiscent of Poe’s idyllic quest than T.S. Eliot’s bleakly modernist view of the ‘meaninglessness’ of human existence in the first verse of perhaps his most despairing work:

T. S. ELIOT

We are the hollow menWe are the stuffed menLeaning togetherHeadpiece filled with straw. Alas!Our dried voices, whenWe whisper togetherAre quiet and meaninglessAs wind in dry grassOr rats’ feet over broken glassIn our dry cellar

Dylan’s own ‘hollow man’ appears in the first verse of Dignity , but really all the characters in this version of the song are hollow men. As such they are projections of the singer himself, whose search for the chimerical ‘Dignity’ has become a futile search for meaning in the humid atmosphere of a symbolic desert landscape. His faith has evaporated and he has, as yet, found nothing to replace it. Later Dylan will take as his touchstone the foundations of the cracked voices of singers like Dock Boggs, Hank Williams and Ralph and Carter Stanley. He will take from these men the foundations of a new kind of ‘faith’ from which will flow a new kind of inspiration. But here, it sounds like he has downed a bottle of tequila and has smashed it against a wall. As he stares out of that ‘platinum window in the Mexican night’ his own soul is naked, exposed and ‘under the knife’. And finally, in reaching down into his inner depths and dredging out his true feelings, he has surrendered all artifice and pretence. It is the only way he can hope to find Dignity.

A different version of this text appears in DETERMINED TO STAND: THE REINVENTION OF BOB DYLAN

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply