BOB DYLAN’S RED RIVER SHORE

The frozen smile upon my face fits me like a glove…

And she bore him a son, and he called his name Gershom: for he said, I have

been a stranger in a strange land

Exodus 2:22

There in the tomb stand the dead upright,

But winds come up from the shore:

They shake when the winds roar,

Old bones upon the mountain shake

W.B. Yeats, The Black Tower

Red River Shore was perhaps the major revelation among all the tracks released on Tell Tale Signs. Its ambition and scope rates with the very best of Dylan’s later work. We are presented two versions of the song, which are almost identical lyrically. This is not, like a number of the other Time Out Of Mind outtakes, a ‘work in progress’. The version on Disc One is the most impressive, beginning with sparse guitar accompaniment and building gradually with the addition of more drums, bass and atmospheric maracas and (in particular) the accordion which comes to dominate the sound. Dylan’s singing here is breathily tender and restrained, reminiscent of the intimacy of the original ‘New York Sessions’ for Blood On The Tracks. The effect is beautifully matched to the tone of humility that underscores the unfolding narrative, tinged with a sweetly savoured sense of regret. Though Red River Shore is a kind of ‘love song’, its concerns are ultimately far wider and more transcendent. In many ways it is a classic piece of romanticism, which echoes the ‘nature poems’ of Burns, Keats, Shelley and Wordsworth. The girl herself seems more elemental than real, a kind of spirit of nature who may be taken to symbolise the poetic imagination itself. Here Dylan uses an authentically mature voice to create a kind of mystical reflection on the power that memory has on our lives as we grow older.

There are in fact two major ‘Red Rivers’ in the US, one in the south between Texas a nd Oklahoma and one in the north between Minnesota and North Dakota. The ‘Red River’ referred to in the famous 1949 Howard Hawks/John Wayne movie is the southern one, whereas one might speculate that the ‘Red River Shore’ Dylan refers to here is the one next to his home state of Minnesota. But unlike Mississippi’, he does not seem to be using US geography in any metaphorical way here. The ‘Red River’ seems to be an entirely symbolic location, with the notion of a ‘red river’ also suggesting blood flowing. ‘Red rivers’ also occur in several folk songs. Most well known is the folk/country standard Red River Valley, a song in which a young girl laments that the cowboy she loves will soon have to leave the Valley. This dates from around 1870 and was first popularized in recorded form in Jules Verne Allen’s 1929 version (known as Cowboy Love Song). It has since been recorded by Jimmie Rodgers, Roy Acuff, Gene Autry, Bill Haley, Woody Guthrie, The Sons OfThe Pioneers and many others. Perhaps more relevant is another traditional song which shares the same title as Dylan’s, which was popularized by The Kingston Trio (who, despite their rather ‘sanitised’ approach to folk music, Dylan cites in Chronicles Part One as an early influence). This song contains the lines … She wrote me a letter/ She wrote it so kind… which Dylan uses in Not Dark Yet, another song from Time Out Of Mind. The song is a cowboy ballad in which the sharpshooting hero’s love for the girl who lives on the shore is thwarted by her highly disapproving relatives. Although he kills a total of thirteen of them, their manpower eventually overwhelms him and he has to retreat. Dylan’s narrator does not face such problems, though he comes no closer to ‘getting the girl’. It could be said that both of these songs hover somewhere in the background here, as both deal with unrequited love. Dylan uses the familiar phrase to help evoke the intense sexual and spiritual yearning that characterizes the song.

nd Oklahoma and one in the north between Minnesota and North Dakota. The ‘Red River’ referred to in the famous 1949 Howard Hawks/John Wayne movie is the southern one, whereas one might speculate that the ‘Red River Shore’ Dylan refers to here is the one next to his home state of Minnesota. But unlike Mississippi’, he does not seem to be using US geography in any metaphorical way here. The ‘Red River’ seems to be an entirely symbolic location, with the notion of a ‘red river’ also suggesting blood flowing. ‘Red rivers’ also occur in several folk songs. Most well known is the folk/country standard Red River Valley, a song in which a young girl laments that the cowboy she loves will soon have to leave the Valley. This dates from around 1870 and was first popularized in recorded form in Jules Verne Allen’s 1929 version (known as Cowboy Love Song). It has since been recorded by Jimmie Rodgers, Roy Acuff, Gene Autry, Bill Haley, Woody Guthrie, The Sons OfThe Pioneers and many others. Perhaps more relevant is another traditional song which shares the same title as Dylan’s, which was popularized by The Kingston Trio (who, despite their rather ‘sanitised’ approach to folk music, Dylan cites in Chronicles Part One as an early influence). This song contains the lines … She wrote me a letter/ She wrote it so kind… which Dylan uses in Not Dark Yet, another song from Time Out Of Mind. The song is a cowboy ballad in which the sharpshooting hero’s love for the girl who lives on the shore is thwarted by her highly disapproving relatives. Although he kills a total of thirteen of them, their manpower eventually overwhelms him and he has to retreat. Dylan’s narrator does not face such problems, though he comes no closer to ‘getting the girl’. It could be said that both of these songs hover somewhere in the background here, as both deal with unrequited love. Dylan uses the familiar phrase to help evoke the intense sexual and spiritual yearning that characterizes the song.

Red River Shore begins with a collocation of extraordinary imagery: …Some of us turn off the lights and we live/In the moonlight shooting by/Some of us scare ourselves to death in the dark/To be where the angels fly… Dylan sets out his stall here, presenting life as a choice between accepting the chaotic nature of existence and letting it overwhelm us. The implication seems to be that if we want to live blissfully (‘where the angels fly’ ) and fulfill our inner longings, we need to accept the ‘darkness’ which surrounds us and learn to live ‘in the moonlight shooting by’, a highly evocative phrase suggesting that a life lived to its full personal and spiritual potential must embrace a certain kind of ‘darkness’. This is a song about choices, but it is not one in which the narrator necessarily makes the right choice. It is a treatise on infatuation, on entrapment, focused on the narrator’s intense love for an unreachable object. The narrator describes a life spent reaching out for someone who is less a real person than a poetic ideal, perhaps a muse, but one who he never has any real chance of getting close to. As the stately tune progresses, Dylan’s subdued and poignant performance conveys his sense of ineffable regret in every breath.

The narrator tells us that despite the … pretty maids all in a row lined up/Outside my cabin door… he has not been distracted from pursuing his love object. The use of the ‘pretty maids’ line from the nursery rhyme Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary next to the reference to ‘my cabin door’ creates an oddly archaic resonance. ‘My cabin door’ is a direct allusion to the great American mid-nineteenth century songwriter Stephen Foster’s Hard Times (covered by Dylan in 1993 on Good As I Been To You). Dylan’s sparing and suggestive use of archaic terms seems to locate the song somewhere in the Foster’s time, when the log cabin itself became a key symbol of the pioneer spirit – Abraham Lincoln was only one of a number of Presidents who made much of their log cabin origins. Red River Shore is also somewhat reminiscent of the wistfully romantic but mournful tone of a number of Foster’s songs, such as Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair. Like the girl from the Red River Shore, Foster’s Jeannie is a kind of lost dream-lover, who is …borne like a vapor on the sweet summer air… We also hear that … Now the nodding wild flowers may wither on the shore/ While her gentle fingers will cull them no more… clearly suggesting that Jeannie is dead. Dylan’s language in this song hints at such an elegiac tone, though ultimately he buries even this assumption in mystery. Foster’s longing for the dead girl is, like that of Edgar Allen Poe in poems like Lenore and Annabel Lee, a stylized and idealized approach which is very characteristic of nineteenth century romanticism and its preoccupation with transcendent death. But despite his apparent immersion in this ‘far away’ world, Dylan constantly jolts us back into everyday reality. He is locked into the romantic illusion of ‘love at first sight’, experiencing a love so powerful that no other love can ever match it. … I knew when I first laid eyes on her… he laments …I could never be free… However, in fact he tells us very little about the girl. Unlike Foster’s Jeannie she seems to have no defining physical characteristics. Yet she has, it seems, something of an acid tongue. After all the narrator’s wooing she advises him, rather bluntly, to …go home and lead a quiet life… Then we hear that his dream of her …dried up a long time ago… He piles on the romantic disillusionment, telling us he’s living under a ‘cloak of misery’, that he can’t ‘escape from her memory’ and that …the frozen smile upon my face fits me like a glove… The awkwardness of the metaphor is another one of the song’s odd lyrical twists. Here he seems to suggest that he willingly submits to the state of paralysis that his memory has locked him into.

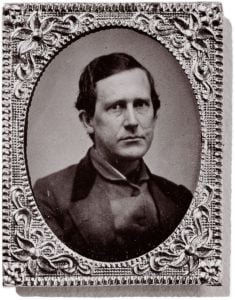

STEPHEN FOSTER

As the song progresses we still learn nothing significant about the girl herself. The singer seems more concerned with meditating upon his own separation from his muse. Alternating between florid poesy and grim realism he tells us he’s …trapped in the fires of time… and …living in the shadows of a fading past… but admits he …never did know the score… and has tried to …stay out of a life of crime… He seems to simultaneously far away from the Red River Shore and standing at its edge. …I’m a stranger here in a strange land… he declares …But I know I’ve stayed here before…. and he dreams of spending the night here ‘a thousand nights ago’ with the girl. He seems to be willingly trapped in a romantic fantasy, in love with a past image of himself and unwilling to free himself from it. But then the narrative takes some very unexpected turns. He tells us he went back to see the girl once to ‘straighten it out’ but that all the people he talked to had no memory of her. Increasingly it seems as if she may have been a mere projection. In the final lines he concludes that … Sometimes I think nobody ever saw me here at all/ ‘Cept the girl from the red river shore… So any solidity his past had had has dissolved. The main theme of the song seems to be not romantic love but the way we can hold onto romantic illusions of the past which may stifle our creativity in the present. This tension lies behind the mostly tortured love songs that make up Time Out Of Mind, depicting the process of an artist trying to free himself from his past.

But there is one more shadow from the past that the singer apparently has to exorcise. In the song’s oddest twist of all we are presented, in weirdly detached language, with what appears to be a reference to Jesus: …I’ve heard about a guy who lived a long time ago/ A man full of sorrow and strife/ That if someone around him died and was dead/He knew how to bring him on back to life… This may in fact be a biblical allusion not to Jesus but to the prophecy of the coming messiah in Isiah 53:3:

He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not.

Yet this is in no way any kind of conventional ‘religious revelation’. The description is strangely offhand and the expression very strange, especially the line ‘died and was dead’. It’s as if the singer has adopted some colloquial ‘uneducated’ tone to refer to ‘this guy’. And the lines remain ominously mysterious. Does the singer want ‘the guy’ to bring ‘the girl’ back to life? Or is he merely grasping at straws? The way ‘the guy’ is introduced and then dismissed in no way indicates any leap of faith. All we are left with in the end is enigma. Did he really know the girl at all? Was any of it real? Can we really trust our memories and should we let romantic illusions overcome us? Can we bring them back to life? The singer has obviously been inspired by ‘the girl’. She seems to have always been his muse. But whenever he tries to conjure her up she slips through his fingers, like a ghost. A ghost of a memory…. In Time Out Of Mind and successive albums Dylan confronts his past, cramming his songs with snippets of what seem like half remembered songs, echoes of what he will later refer to as .. long dead souls from their crumblin’ tombs… evoking past scenes through the prism of the present. The implication seems to be that only be accepting the truth of the past can we be free from it. So we can avoid …scaring ourselves to death in the dark… and live in the fullness of the present moment, within …the moonlight shooting by…

A different version of this text appears in DETERMINED TO STAND: THE REINVENTION OF BOB DYLAN

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply