BOB DYLAN: NARROW WAY

…Straight is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life,and few there be that find it – King James Bible, Matthew 7;14

For this the Golden Sun the Earth divides

And, wheel’d thro’ twelve bright signs, his chariot

guides.

Five zones the heav’n surrounds: the centre glows

With fire unquench’d, and suns without repose:

At each extreme the poles in tempest tost

Dark with thick show’rs, and unremitting frost:

Between the poles and blazing zone confin’d

Lie climes to feeble man by Heav’n assign’d.

‘Mid these the signs their course obliquely run,

And star the figur’d belt that binds the sun…

Virgil’s Georgics Book 1 V 277-302 transl. William

Sotheby (1800)

I’ve got a heavy stacked woman with a smile on her face

And she has crowned my soul with grace…

If the sub-Crosby ballad Soon After Midnight is tenderly romantic, the repetitive, grinding blues riff that drones throughout Narrow Way is one clue that here we are entering much more ‘down and dirty’ territory. It’s going to be quite a ride. Narrow Way is full of wild allusions and associative imagery that

sometimes resemble those of Dylan’s classic 65-66 period. Dylan growls through

the song, thoroughly inhabiting the cynically lustful ‘grumpy old man’ persona

established in Duquesne Whistle. The music itself hardly varies throughout the seven minutes twenty eight seconds of the recording. The effect is of a narrator who seems to be doggedly plodding through some kind of hostile landscape. …This is a hard country… he mutters darkly …to stay alive in… Blades are everywhere/and they’re breaking my skin… The setting of the song is continually shifts through space and time. Sometimes the singer appears to be addressing a particular woman and at other times he ruminates about her. He seems to have experienced some kind of betrayal yet his anger at this this is finally succeeded by a kind of lustful epiphany, in which ‘spiritual’ concerns are superseded by earthly pleasures. As in many of the best blues songs, however, the sexual bragging the singer indulges in is ambiguous. Does the singer really mean what he is saying? Or is he just teasing us?

One of the most immediately noticeable features of the song is the lyric plays around with ‘spiritual’ allusions. Although the title Narrow Way, with its very well known biblical connotations, suggests that this might indeed be one of those ‘religious songs’ Dylan (perhaps mischievously) claimed he was trying to write at the time, and although the lyrics are indeed concerned with ‘spiritual matters’, the Biblical references seem to be thrown in rather playfully into a song which gleefully conveys a very ‘freewheeling’ view of how the ‘path to salvation’ can be achieved. The narrator’s tone sometimes recalls Dylan’s animation of God’s ‘hipster jive’ conversation with Abraham in Highway 61 Revisited, with the ‘sacred’ and the ‘profane’ being juxtaposed in deliberately provocative ways. The song is built around a refrain borrowed from the Mississippi Sheiks’ 1930s blues You’ll Work Down To Me Someday. In the original the narrator sounds rather hurt and angry with his lover, adopting a rather rhetorically ‘humble’ posture. However, Dylan’s spirited diction (and the sly addition of the word ‘surely’) twists the words into a sexually suggestive motif, as if he is really asking her to ‘work her way down’ his body. Is this an invitation for fellatio or an admission by the singer that he is ‘below her’ in the sexual pecking order? Or is he (perhaps rather cheekily) addressing some ‘higher power’, begging for his failing faith to be restored? Dylan has always enjoyed the way in which the blues can give a singer license to use sexual metaphors to comment on social and religious issues, so that the poetry of such songs can stand alone – leaving the interpretation to the listener, and allowing the ‘meaning’ of the words to be always open to variation. In Narrow Way, despite its apparently dark themes, he pushes this element of comic ambiguity to its limits.

BLIND WILLIE McTELL

Dylan has also always demonstrated his understanding of the fact that humour is an important element of the blues. Much of his early repertoire consisted of satirical ‘talkin’ blues’ songs and wacky bluesy numbers like Freewheelin’s mock-romantic Honey Just Allow Me One More Chance. By the mid ‘60s, in Outlaw Blues, Maggie’s Farm, On The Road Again and From A Buick 6, he had developed a form of surreal comic invention based on blues structures which reached its apogee on the masterful mocking of social pretensions on the hilarious Chicago-blues Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat. Later examples include the lugubrious ‘shaggy dog’ story Highlands (1997) and the quasi-political ruminations of Tweedle Dum And Tweedle Dee (2001), not to mention the unfairly maligned Wiggle Wiggle (1990), actually an ingenious tongue-in-cheek ‘children’s song about sex’. In many songs by Dylan’s favourite blues, artists sex and religion are juxtaposed with wry humour. The Mississippi Sheiks’ He Calls That Religion mocks a preacher who …used to reach just to save souls/ But now he’s preachin’ just to buy jelly roll… In Blind Willie McTell’s Lord Send Me An Angel, the singer pleads to God to help him overcome not only his lustful urges but also his apparently unfailing attractiveness to women. Willie sings: My baby studying evil and I’m studying evil too/ Gonna hang round here to see what my baby gon’ do/ I can’t be trusted and I can’t be satisfied/ When the men see me coming, they go pin their womens to their side…

In Narrow Way Dylan adopts a similarly self-mocking tone, yet his narrative stance is continually being refocused. Its narrator appears (at least some of the time) to be addressing (and sometimes referring to) a (very raunchy) lover. At other times he appears (in a bizarre, even ‘blasphemous’ way) to be castigating Jesus directly, suggesting that it is his choice of ‘earthly pleasures’ that has in fact ‘saved’ him.

In the first verse, we meet the song’s protagonist, a ‘spiritual wanderer’ who has apparently retreated into the desert to make some sense of life. It may be significant here that the end of the first line: …I’m gonna walk across the desert ‘till I’m in my right mind… references one of Dylan’s earliest mentors, the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg. In America, his great poem of rejection of the 1950s patriotic American ethos, perhaps the most memorable and striking (and of course, controversial) lines are these:

America

when will we end the human war?

Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb.

I don’t feel good don’t bother me.

I won’t write my poem till I’m in my right mind

ALLEN GINSBERG

Thus Dylan’s narrator, like Ginsberg, needs to liberate himself from preconceptions in order to be able to ‘think straight’. He seems to have walked away from his home and his family and his previous beliefs. A voice is whispering in his ear, but he tells it to …Go back home/ Leave me alone… He has rejected any connection with his previous existence: …Nothing back there that I can call my own… The first chorus suggests that he is on his own path to

salvation, or enlightenment, and that the ‘voice’ that is calling to him will have to make a considerable effort to reach him. The parallel with the Biblical story of Jesus’ ‘forty days and nights’ in the desert is rather obvious, but here the disillusioned narrator is rather scathingly rejecting the advances of the ‘spirit’ that is following him and ‘whispering in his ear’. As yet we do not know whether this ‘voice’ is that of God or the devil, and neither, perhaps, does the narrator. But it is clear that he is disillusioned with conventional ways of thinking, and that certain events have made him extremely angry.

There seems to be a clue to the nature of these events in the next verse with its rather bizarre allusion to American history, referring to when the British burned the White House down in the war between Britain and the USA in 1814. Ever since this, the narrator declares … there’s a bleeding wound in

the heart of town… This war, sometimes known as the ‘Second War of Independence’ had great significance in American history in that it marked the point at which the USA began to employ a professional army and thus to assert itself on the world political stage. It largely resulted in victories for the USA, especially in the battles of Baltimore, Pittsburgh and New Orleans. The reference seems to suggest that the US is carrying some kind of ‘stigmata’, or some unhealed or festering abrasion. The weirdly fractured quasi-Biblical references then begin to pile up. …I saw you drinking from an empty cup.. the narrator cries, …I saw you buried and I saw you dug up… and then …I kissed your cheek, I dragged your plow/ You broke my heart, I was your friend ’til now… These appear to be allusions to the Last Supper, the resurrection and Jesus’ betrayal in Gethsemene. Yet the language used is curt, almost brutal. Even more scathing are the lines …You went and lost your lovely head/ For a drink of wine and a crust of bread… and later …Your father left you, your mother too/ Even death has washed it’s hands of you… The narrator appears to be callously rejecting the Jesus-figure who is whispering in his ear. The references to ‘bread and wine’, the crucifixion and the resurrection and the ‘washing of hands’ (as in Pontius Pilate) are made with apparent disdain. This rejection appears to be linked with the fact that the narrator appears to be fleeing some kind of war zone. …This is a hard country to stay alive in… he tells us. There is an odd reference to …the courtyard of the golden sun… which seems to evoke an image of the Inca capital at Cuzco, which was smashed by the Conquistadors who were committing their genocide, which was carried out, of course, ‘in the name of the Lord’. The narrator seems to be making a link between Christianity and imperialism (and perhaps American ‘imperialism’ in particular. This is reinforced in the lines … We looted and plundered on distant shores… which is followed by the vituperative ….why is my share not equal to yours?… This suggests, if we did not know already, that this not necessarily a sympathetic narrator.

The juxtaposition of coarse and religious language in the song continues to be both striking and jarring. Following the references to American history, a number of lines seem to be alluding to popular American hymns. The refrain of At The Gate That Leads To Glory by the nineteenth century hymnodist Fanny Crosby runs: …Strait is the gate and narrow is the way/ That leadeth unto life above/ Strive to enter in, oh, strive to enter in!/Come to a Saviour’s love… We have already seen how Dylan has twisted this around here. Another popular hymn, Dear Refuge Of My Weary Soul (written by Anne Steele in 1717) begins: …Dear refuge of my weary soul, On thee when sorrows rise/ On thee, when waves of trouble roll, My fainting hope relies… Here Dylan’s narrator cries …Look down angel from the skies/ Help my weary soul to rise… but is apparently not heard. Another popular hymn O For A Thousand Tongues To Sing is parodied here in the next verse, in which the narrator’s rejection of his ‘saviour’ becomes quite explicit: …You got too many lovers waiting at the wall/ If I had a thousand tongues I couldn’t count them all… Then the narrator continues, rather helplessly: … Yesterday I could’ve thrown them all in the sea/ Today even one may be too much for me…

As the song nears its (almost literal) climax, the narrator now seems to be making a direct address to a woman with whom he can satiate his lust as so achieve his ‘deliverance’. He addresses her as …cake walking baby…. This is a reference to a popular ‘dirty jazz’ tune of the 1920s, Cake Walking Babies From Home, a favourite of Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet and Bessie Smith. The song begins: …Cake walkers may come, cake walkers may go, but I wanna tell you ’bout a couple I know/ High steppin’ pair, Debonair/ When it comes for bus’ness not a soul can compare… These ‘cake walkers’ are a couple of notable prostitutes who are unafraid to ‘strut their stuff’ across town. With little ambiguity, Dylan’s narrator tells the woman he wants to take her on a …roller coaster ride… and to …lay my hands all over you… In the next verse he memorably declares … I’ve got a heavy stacked woman with a smile on her face/And she has crowned my soul with grace… The juxtapositioning of sexual and religious imagery is quite explicit (and really very delicious!) here. But the narrator is prepared to go even further: I’m still hurting from an arrow that pierced my chest/ I’m gonna have to take my head and bury it between your breasts.. Dylan pronounces the lines with great relish. He rather mockingly (even ‘sacrilegiously’ refers to himself as a martyr here. But sex is his salvation. Not true love, but ‘unspiritual’ lust. A ‘narrow way’ to ‘Amazing Grace’ indeed…

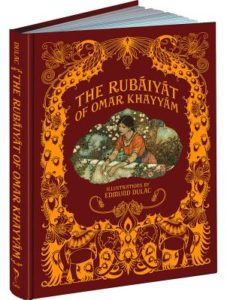

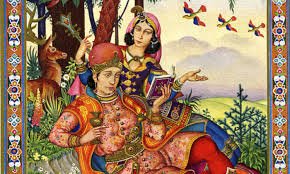

Finally, the narrator has been ‘saved’. He tells the ‘heavy stacked woman’ that …You can guard me while I sleep/ Kiss away the tears I weep… Dylan reinforces this with a couple of quotations from Edward Fitzgerald’s renowned translation of the eleventh century Persian hymn to hedonism, The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam, in which the poet extols the virtue of earthly pleasures and finds in them a kind of spiritual awakening. Life is seen as a continual ‘moveable feast’: …The Moving Finger writes: and, having writ, Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit/Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line, Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it…. Dylan paraphrases this here: Been dark all night but now it’s dawn/The moving finger is moving on… Khayyam’s poem also famously describes how he discerns a spiritual meaning in an ordinary earthly process, the turning of a potter’s wheel. …For in the Market-place, one Dusk of Day/I watch’d the Potter thumping his wet Clay/And with its all obliterated Tongue/ It murmur’d—“Gently, Brother, gently, pray!”… Dylan’s lines in the final verse …I heard a voice at the dusk of day/ Saying, “Be gentle brother, be gentle and pray.” clearly point us towards an experience of true spiritual awakening being achieved through everyday life-giving processes. In a Zen-like moment of revelation, having first rejected God (or ‘enlightenment’) the narrator has finally found it (or ‘Him’, if you like). Thus: …If I can’t work up to you, you’ll surely have to work down to me someday… Yet Narrow Way is neither a statement of belief in nor a ‘rejection’ of conventional religion. Dylan is clearly singing through the voice of a character he has created. In some ways this character resembles the ageing (and often lustful) voice of the previous two songs, one who is weary of spiritual struggle and who wishes to take part in earthly pleasures while he is still able. What this song (and the others on Tempest) clearly does not to is present any kind of ‘religious’ message or dogma. Dylan’s mature work engages deeply with religious concepts but he always leaves us to draw our own conclusions. He is a poet, not a preacher. In his great song of self-examination My Back Pages (1964) he had long ago rejected the ‘preachy’ elements that may have affected his earliest incarnation as a ‘protest singer’: In a soldier’s stance, I aimed my hand at the mongrel dogs who teach/ Fearing not that I’d become my enemy in the instant that I preach… As a symbolist poet, Dylan presents the listener with images that cannot be reduced to a simple ‘message’. His use of shifting perspectives also enables him to present a point of view without necessarily identifying with it himself. This will be most clearly demonstrated later on in this album’s extraordinarily violent Pay In Blood. His singing style here, like the musical mode he uses, has some similarity to that of the mid 60s, when he took so much pleasure in wrapping ringing phrases around his tongue, presenting his listeners with endless pleasure in interpreting his words. What are we to make, then, of these lines in the final verse of Narrow Way: …I love women, and she loves men/ We’ve been to the west and we’re going back again…? Given that the action of a song takes place in a desert, and that it features a character who is being subjected to ‘temptations’, and that the desert in which Jesus is supposed to have undergone such temptations is now the very location of a ‘war on terror’ between members of different religions, can we then place this song in a contemporary context? Does ‘the west’ here represent the site of free-thinking, of religious freedom? Or does it represent that kind of religious hypocrisy and imperialism that was under attack earlier on. Well, maybe. But we have to remember that, despite the dark places this song takes us to, Narrow Way is – like many of Dylan’s greatest songs – fundamentally encouraging us to look at life with a light heart. Or as Omar Khayyam puts it:

Here with a loaf of bread

beneath the bough,

A flask of wine, a book of verse—and thou

Beside me singing in the wilderness—

And wilderness is paradise enow.

A different version of this text appears in DETERMINED TO STAND: THE REINVENTION OF BOB DYLAN

—————————————————————————————–

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply