Tangled Up in Blue: A ‘Tangled Web’

Tangled Up in Blue, the opening song on Blood on the Tracks, is Bob Dylan’s most ‘open ended’ creation. Since 1975 Dylan has performed the song around 1600 times, using many different musical arrangements. The continuing variations in the lyrics reflect the highly ambiguous way that Dylan allows the story to unfold. We can never be sure whether the characters referred to as ‘he’, ‘she’ and ‘I’ are the same people from verse to verse, what the time sequence of the narrative actually is, or where the events being described are taking place. The singer weaves a ‘tangled’ web indeed…

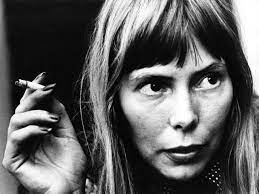

By 1974, it appeared that Dylan’s position as the most influential rock singer-songwriter was being usurped by other artists who had become successful in his wake. From 1969’s Nashville Skyline onwards he had released albums like New Morning (1970) and Planet Waves (1974) on which many of the songs were much simpler and less adventurous than those of his mid-60s heyday. They also reflected his personal situation as a married man with a large and growing family. Meanwhile, artists like Joni Mitchell, John Lennon, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, David Bowie and Jackson Browne seemed to be pushing at the limits of poetic song in ways that Dylan seemed to be shying away from. On Song for Bob Dylan from 1971’s Hunky Dory Bowie makes this explicit by imploring Dylan to return to more adventurous forms of song writing. It has been reported that Dylan was inspired to write Tangled Up in Blue after spending a weekend listening to Mitchell’s album Blue (1971), her last set of solo acoustic songs. The open guitar tunings on Blood on the Tracks appear to be influenced by her use of this technique on her album.

A popular rallying cry of the 1970s, an era in which traditional views of love and marriage were being challenged, was ‘the personal is political’. By the mid 1970s, the songs of Mitchell, Browne and others were taking up the approach that Dylan had used in early songs like Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright, Mama You Been On My Mind, One Too Many Mornings and It Ain’t Me Babe. Such songs (which were profoundly influenced by the tradition of emotional realism in country music in the work of singers like Hank Williams, Loretta Lynn and Johnny Cash) examine intimate personal relationships with a kind of fatalistic detachment. Very often they depict relationships which had now fallen apart. Their narrators tend to be philosophical, rather than heartbroken, about the break ups. On albums such as Blue, Young’s After the Goldrush (1970) and Browne’s Late for the Sky (1973) the singers appear to be taking metaphorical scalpels to their own personal experiences. In brilliantly incisive songs such as The Last Time I Saw Richard and A Case of You, Mitchell dramatises her own notoriously unstable relationships through the prism of feminist sexual politics while dwelling self reflectively on her own personal failings. On California she admits to being …strung out on another man… In Fountain of Sorrow Browne addresses a former lover, admitting that the ‘magic feeling’ that occurs at the beginning of relationships …never seems to last… In the confessional Bird on a Wire Cohen reflects, perhaps unconvincingly, that …it was the shape of our love that twisted me… In Tell Me Why Young admits candidly, if paradoxically, that …It’s hard to make arrangements with yourself…

‘Tangled’ Albums By Other Artists

Such self-deprecating ‘soul searching’ songs related stories that, often with the full knowledge of listeners, reflected real events and relationships in the singers’ lives. In his stripped down ‘confessional’ album John Lennon/ Plastic Ono Band (1971) the former Beatle presented his ‘personal politics’ in the most extreme and autobiographical form, even ending the album with a short, haunting but apparently ‘throwaway’ ditty My Mummy’s Dead. Joni Mitchell had a string of relationships in this period – some with other famous musicians – which, on Blue, she dissects with razor-sharp clarity. Perhaps the most distinctive line on her album occurs in A Case of You (said to be about her relationship with Cohen) in which the unnamed male romantic figure assures her that he is … as constant as the Northern Star… (a famous line from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar). Mitchell’s female narrator merely shrugs at this hackneyed ‘chat up line’: …Constant in the darkness?… she sneers… Where’s that at?/ If you want me I’ll be in the bar…

Dylan’s ‘Tangled’ Life

By the time Dylan wrote the songs on Blood on the Tracks he had emerged from several years of seclusion and begun touring again. Meanwhile his personal life was clearly undergoing considerable change, with his marriage now ‘on the rocks’. Although he has always kept his personal life as confidential as possible, rumours also persisted of his having had several clandestine affairs. When the collection appeared, it was clear from the often anguished emotions being expressed in deeply heartfelt songs such as If You See Her Say Hello, Simple Twist of Fate and You’re a Big Girl Now that this was indeed a ‘break up album’. It was hard for listeners not to identify the narrators in the songs as being the authentic voice of Dylan himself. Yet Dylan’s approach is very different to that of Mitchell’s. Although the songs on Blue are among the most eloquent ever written about the unreliability of relationships, and despite the layers of irony which Mitchell so skilfully projects, she uses her narrative techniques to make the actual meaning of her almost shockingly honest lyrics crystal clear. Like Mitchell, Dylan uses largely colloquial and conversational language but his approach on Blood on the Tracks is to present the stories of relationships within the songs through multiple layers of ambiguity. This is established especially through the use of narrative and temporal shifts.

Dylan once claimed, rather mischievously if somewhat unconvincingly, that the songs on the album were not ‘about’ the breakup of his own marriage but were actually based on the short stories of Anton Chekov. He also later stated that the 1976 song Sara, perhaps the most clearly autobiographical song in his entire catalogue, was not actually about his estranged wife but referred instead to the Biblical wife of Jewish patriarch Abraham. Such statements appear to represent Dylan trying to lead us away from simplistic interpretations of his songs. But while Sara clearly is ‘about’ his own marriage, the songs on Blood on the Tracks are emotionally complex and consistently ambiguous. Some wallow in emotional despair, whereas others – like the spoof ‘cowboy ballad’ Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts, the romantic You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go and the jokily philosophical Buckets of Rain – are light hearted and even comical. Despite Dylan’s denial, it is clear that there are very personal echoes of his own life here, although to read them as ‘the story of Bob and Sara’ is far too simplistic. Blood on the Tracks is a kind of treatise on the vagaries of and the moral contradictions of ‘grown up’ relationships for which the figure of ‘Bob Dylan’ is merely one of the shifting signifiers.

Dylan and Raeburn

The key to Dylan’s approach to the songs has often been indicated by his statements about the influence of art teacher Norman Raeburn, whose classes in New York Dylan attended during this period. By explaining to Dylan about how the great painters of modern art could produce images which could be viewed from several different perspectives at once, Raeburn seems to have inspired him to replicate such techniques in songs – a quite revolutionary and original approach influenced most prominently by the work of Pablo Picasso. In his Cubist paintings Picasso defies the laws of perspective to paint figures so that we appear to be looking at them from several angles at once. Such a perspective is particularly appropriate when describing the vicissitudes of love relationships, which may often be viewed in completely valid ways from the angles of more than one protagonist. In Tangled Dylan applies this technique to the most obvious and distinctive effect.

Blood on the Tracks was originally conceived of as a mostly acoustic album – a throwback, in some ways, to Dylan’s early work. The first sessions for the album – recorded in New York – mostly featured Dylan alone or accompanied only by bass player Tony Brown. Many of the tracks were later rerecorded in Minneapolis with a full band. A bootleg of the ‘New York Sessions’ circulated fairly soon after the release of the album, causing aficionados to gasp in wonder that there actually apopeared to be another version of the highly acclaimed album. It was clear that, on many tracks, these recordings equalled or even surpassed the official release in terms of emotional impact. Tangled, however, is one track that benefits greatly from the increased instrumentation. Even in its acoustic incarnation it has a very strong and pronounced rhythm throughout. In the ‘electric’ version this insistent pattern is given more emphasis. Musically, Dylan sticks as usual to a simple format, with each verse following the same relentless rhythmic pattern. This works as a contrast against the deliberate confusion in the lyrics.

‘Tangled’ Structure

The song has seven verses. Each verse has twelve lines with the addition of the repeated title line at the end and these are divided into three groups of four lines. Dylan uses an ABAB rhyme scheme throughout. At the end of each verse, the final ‘B’ rhyme is followed by a short phrase that rhymes with ‘blue’. This structure remains in place throughout the many different versions of the song, giving an extra ‘kick’ to the repetition of the title. The title itself works as a summation of the song, powerfully expressing the mental confusion of the narrator, who is just as ‘tangled up’ at the end of the song as he was at the beginning.

Out on the Road

The first verse changes the least through the different iterations of the song, except for frequent changes between first and third person. The ‘New York’ version begins …Early one morning the sun was shining/ He was lying in bed… On the album take ‘he’ is changed to ‘I’. The protagonist is thinking about a woman he loves, who has had a relationship with in the past, wondering if …her hair was still red… As some commentators have noted, this could be read as a reference to Dylan’s first wife Sara, who was indeed red headed. However, there is a suggestion that a considerable amount of time may have passed since the couple were lovers. Perhaps her is looking back from the far future. Her hair has turned grey by now and he is merely indulging in hopeless nostalgic reminiscences… He suggests that the woman’s parents did not approve of him because of his apparent poverty: …They never did like mama’s homemade dress/ Poppa’s bankbook wasn’t big enough… which is supported by the depiction of him hitch hiking at the end of the verse with ‘rain falling on his shoes’. We are also told that he is heading East, one of a number of sometimes contradictory directions we are given.

It may be that the protagonist is relating the entire tale while ‘standing at the side of the road’ hoping for a ride. This links the song with Jack Kerouac’s beat masterpiece On the Road, in which characters frequently ‘take to the road’, despite their lack of funds, in a quest for a peculiarly American kind of freedom. Although the main character may present us with snippets of ‘the life of Bob Dylan’, he also (more disturbingly) resembles Dean Moriarty, the hero (or perhaps anti-hero) of Kerouac’s novel. Kerouac’s narrator Sal Paradise holds Moriarty in great esteem, despite portraying him as an inveterate philanderer who treats women with manipulative disdain. Just as On the Road thrives on the tension between the characters’ desires to find love and ‘settle down’, in Tangled Up in Blue our protagonist is ‘entangled’ within such contradictory impulses. This is reflected in the next lines …She was married when we first met/ Soon to be divorced… is another snippet of biographical detail which could be related to Dylan’s own life – Sara was indeed married when they first met. But in the next line the protagonist is already confessing that: …I helped her out of a jam I guess/ But I used a little too much force… suggesting that – like Moriarty – he was far too ‘pushy’ or manipulative with her. Then we hear that the two lovers drive a car ‘as far as they could’ out West until they finally abandon it; another scenario that mirrors the action in On the Road. We are told that the couple then splits up and go their separate ways, although the reasons for this are not stated. In the acoustic version she had merely told him …This can’t be the end/ We’ll meet on another day… But now we conclude with a telling vignette: …She turned around to look at me/ As I was walking away/ I heard her say over my shoulder “We’ll meet again someday….” The woman’s words echo the 1940s Vera Lynn wartime classic song We’ll Meet Again – a song which was especially resonant among war brides who knew full well that their husbands might not return from the battlegrounds. …Don’t know where… the woman might have added …Don’t know when…

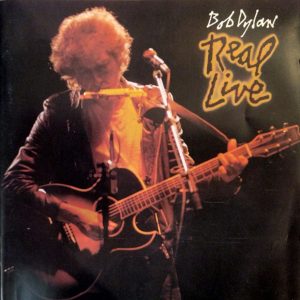

JACK KEROUAC

In the original acoustic version, and in many subsequent live performances, Dylan uses the second person ‘he’ rather than ‘I’ in the first four verses, before switching to the first person in the last three. In the heavily rewritten iteration of the song performed on the 1984 tour (a version of which appears on the Real Live album) the narrator indulges in some colourful comic exaggeration, beginning …She was married when they first met/ to a man four times her age… We are told that …He left her penniless in as state of regret… and then declares, using a rather random metaphor, that …It was time to bust out of the cage… Here, with the added distance of third person narrative, the self deprecating tone of the recorded version is absent. The changed lines at the end of the verse are also noticeably more wistful and romantic: She turned around to look at him/ As he was walking away/S aying “I wish I could tell you all the things/ That I never learned to say”/ He said “That’s alright, baby, I love you too…” As time goes by, Dylan’s sympathy with (and perhaps compassion for) the protagonist appears to grow.

‘Tangled’ in Kerouac

In the following verse, the protagonist behaves exactly like one of Kerouac’s characters, drifting around the country doing odd jobs. Firstly we are told he had a job as a cook ‘in the Great North Woods’ but then …one day the ax just fell… Like Moriarty, he characteristically takes no responsibility for his being sacked from the job, the description of which is tied together with a neat little pun linking axes and trees. Perhaps Dylan is identifying himself with Moriarty in order to present himself as a potentially unsympathetic character. The song is full of the excuses which the main character makes to justify his actions. We find him ‘drifting down’ to New Orleans where he works in a fishing boat …just outside of Delacroix… It should be noted here that the Great North Woods are in Maine, several thousands of miles from New Orleans. In the acoustic version he works …loading cargo onto a truck… in Los Angeles, which is of course even further away. It seems that the protagonist, like Moriarty, frequently escapes from relationships by criss-crossing the country. Yet he just cannot get the woman out of his ‘tangled’ mind. Thus, as in On the Road, the geography of America itself, with its great vastness and variety, works as a simulacrum for the dilemma of the main character, who is caught between apparently separate roads that lead to stability and freedom. The position of the protagonist also recalls the girl being addressed in Like a Rolling Stone, who is now ‘out on her own’ having chosen to follow the urge for personal freedom to its unknown conclusion. Thus Dylan’s song encapsulates the key themes of the counterculture of the 1950s and 1960s from a distinctly more cynical and less idealistic 1970s perspective.

The version played at Charlotte South Carolina on 10/12/1978, with its stately ‘big band’ arrangement, includes a few changes here. The protagonist is now …living in a vagabond hotel…. in the Great North Woods. We also hear that he suffers a life threatening accident with ‘boiling fat’ near Delacroix. In the ’84 version we begin rather comically, with the protagonist having ….a steady job and a pretty face… We also hear that, for unspecified reasons, he …nearly went mad in Baton Rouge/ He nearly drowned in Delacroix… The song also contains a rare direct address to the woman: …He had one too many lovers and/ None of them were too refined/ All except for you… His fate in the Louisiana area is frequently changed. In 2012 he almost drowns, having been ‘treated like a tramp’. Dylan plays around with the physical details, sometimes changing the words at random or improvising changes. But whatever calamity occurs is really irrelevant. The point is that he is a drifter who is subjected, like Kerouac’s characters, to various indignities but manages to survive.

Versions of ‘Tangled Up in Blue’

At this point in the acoustic version, the narrative switches from the third to the first person until the song ends. Dylan presents the scenarios with great narrative economy, leaving much room for speculation. Firstly he tells us that …She was working in a topless place/ When I stepped in for a beer… We may presume that the woman is a dancer or waitress. Dylan keeps the details to a minimum, maintaining that …I just kept looking at the side of her face in the spotlight so clear… His protagonist is about to leave when she appears behind his chair …Don’t I know your name?… she asks him. Obviously feeling rather awkward, he merely mutters …something underneath my breath… to her. And then, in perhaps the song’s funniest lines, he confesses that …I must admit I felt a little uneasy when she bent down to tie the laces of my shoe…. Again the lines may have some relevance to Dylan’s own history. Sara, a model and actress, once worked for Playboy as a bunny girl. Her reaction, like that of the waitress in 1997’s Highlands, appears to recognise him as a ‘famous person’. She makes him feel awkward by ‘tying his shoelaces’ as if she is paying some kind of tribute to him. Dylan himself is well known to avoid media invasions into his private life. On the other hand, so few details are given about the encounter that the protagonist may not be Dylan himself but a figure not so far removed from the sex-obsessed Dean Moriarty. The woman may be propositioning him for financial reasons by bending over sexily in front of him.

This is another verse to which Dylan applies radical changes throughout the history of the song. In the Charlotte ’78 performance the woman is described as a ‘dancer in the Flamingo club’ (presumably the one in New York) who tells him …Well, it ain’t no accident that you came… The implication here appears to be that she already knows him and that he has deliberately sought her out. In the ’84 version they merely engage in a rather inscrutable exchange as she asks him …What’s that you got up your sleeve…/ I said “Nothing, baby, and that’s for sure… The encounter then becomes more explicitly sexual, if perhaps rather uncomfortable for him: … She leaned down into my face/ I could feel the heat and the pulse of her as she bent down…

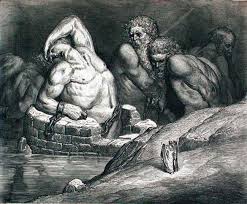

In the next verse the encounter with what may or may not be the same woman follows a very different trajectory. We are now in some kind of cosy domestic setting. She …lit a burner on the stove and offered me a pipe… presumably containing marijuana. Then she becomes mischievously flirtatious …”I thought you’d never say hello,” she said, ”You look like the silent type… We may think that a seduction is soon to occur but instead she shows him a book of poems …written by an Italian poet from the thirteenth century… This revelation clearly affects him deeply. He enthuses that …Every one of them words ran true and glowed like burning coal/ Pouring off of every page like it was written in my soul… There has been much speculation about who the ‘Italian poet’ might be. The imagery of ‘burning coals’ suggests that he may be referring to Dante, author of the descent into hell described in Inferno. If this is so, we may suppose that the protagonist is about to experience some kind of spiritual transformation. He has been seduced, it seems, through shared intellectual interests. Alternatively, we may speculate that she may be trying to lure him into some kind of pit of ‘hellish’ sinfulness. It’s important to remember, though, that everything is being described to us through the words of this unreliable narrator, who seems to be presenting himself as an innocent victim here. We can only speculate as to how the woman (or women) in these two verses might describe the encounters.

Changing lyrics in Tangled Up in Blue

This is another verse which undergoes many changes. In the Charlotte ’78 version the woman is described as …Wearin’ a dress made of stars and stripes… Instead of showing him the book of poems she quotes Jeremiah Chapter 17, verses 21 to 33 to him. This was the first indication to Dylan’s audience of his imminent conversion to ‘Born Again’ Christianity. The verses in question refer to a covenant between God and Man. Dylan’s 1980 album Saved contains the song Covenant Woman, who we are told has a …contract with the Lord… If the original version was referring to Sara, this may be referring to Mary Ann Artes, one of Dylan’s lovers who introduced him to the Christian Vineyard Fellowship. In the ’84 version the verse is omitted but in the 2013-16 version (itself reduced to four verses) there are more radical changes. We hear that: …She lit a burner on the stove/ And brushed away the dust/ Well, she looked at me and she said to me/ “You look like somebody I can trust… After showing him the book of poems she tells him to …Memorize these lines and remember these rhymes/ You can use them when you’re walking to and fro… By now both the pot smoking and religious lines have been replaced, as has the reference to the ‘Italian poet’. It seems that Dylan may be trying to remove lines which have been misinterpreted or over interpreted in the past.

As the song reaches its climax we are led further into its ambiguous ‘tangle’. In the first two sets of four lines in the original, more ‘laid back’ acoustic version of this verse we hear that …He was always in a hurry/ Too busy or too stoned/ And everything that she ever planned/ Had to be postponed… In the revised ‘electric version’ the verse begins …I lived with them on Montague Street, in a basement down the stairs… but it is still not made clear who ‘they’ are. Could it be that the narrator has been describing two other people throughout? Montague Street is in a bohemian area of Brooklyn and in the next line Dylan sums up the mood of the 1960s with great economy. …There was music in the cafes and night and revolution in the air…

ARTHUR RIMBAUD

Then the song takes perhaps its strangest turn. We hear that…Then he started into dealing with slaves and something inside of him died… This is often taken to be a reference to the nineteenth century French poet Arthur Rimbaud (mentioned in You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go) who was a major influence on Dylan’s early work. Perhaps now he is identifying the Moriarty figure (who can be said to represent the ‘dark side’ of the counterculture) with the bohemian poet, who gave up writing at the age of 19 and was rumoured later in life to have become a slave trader in Africa. Conversely, it could be that the figure being referred to has become a pimp who is controlling the female character, who …had to sell everything she owned and froze up inside…. (in contrast, perhaps, to the ‘burning coals’ mentioned earlier). The narrator describes how the shock of this apparent betrayal leads him to become ‘withdrawn’ but concludes rather philosophically by stating that …The only thing I knew how to do was to keep on keepin’ on…. This phrase became a cliché of the counterculture in the 1960s. Here it clearly identifies the narrator as someone who rejects conventional values.

The ’78 version has a few minor changes here, describing how the woman has to sell …even her jewellery and clothes… because of the man’s exploitation. In ’84 we are told that …one day all of his slaves ran free… The narrator catches a train back down South. He sounds thoroughly disillusioned: …I didn’t know whether the world was flat or round… he tells us …I had the worst taste in my mouth/ That I ever knew…

A ‘tangled’ expose

The final verse underlines the narrator’s determination to ‘keep on keepin’ on’. He declares that he has to find ‘her’ again (although which of the apparently different women in the song he is referring to is unclear). In a few resonant lines he demonstrates his disillusionment with ‘fellow travellers’ who have apparently returned to more conventional lifestyles: …Some are mathematicians/ Some are carpenter’s wives/ I don’t know how it all got started/ I don’t know what they’re doing with their lives…. He tells us that such people are just an ‘illusion’ to me now. In the highly evocative concluding lines he gives us a cry of defiance: …Me I’m still on the road/ Heading for another joint/ We always did feel the same/ We just saw it from a different point of view… This in itself is a kind of summation of the whole song, which tells a story told from ‘different points of view’. No doubt Dylan’s many ‘alternative’ fans were delighted by the line ‘heading for another joint’, inferring that the narrator is still searching for the kind of freedom that Kerouac sought – and still getting stoned. But in America a ‘joint’ can also refer to a dwelling, or a rundown place to perform music. It is also a slang word for a prison. Kerouac’s romanticisation of the ‘pre-hippie’ lifestyle in On the Road was an intellectual model for the 1960s counterculture and – like so many ‘Great American novels’ from Moby Dick to Huckleberry Finn to The Great Gatsby – a kind of ‘tangled’ expose of the hollowness of the ‘American dream’.

The ’78 version lacks the triumphal spirit of the recorded version. The narrator is more humble. …I got to get to her and be brave…. he tells us. The ‘mathematicians and carpenter’s wives’ are replaced by ‘bricklayers, bank robbers, burglars and truck drivers’ wives’. These lines are possibly the most changeable in the song. ‘Doctor’s wives’ is another common substitution. In the ’84 version we get …Some are masters of illusion/ Some are ministers of the trade/ All of the strong delusion/ All of their beds are unmade… In the 2013-16 performances he substitutes: … Some of them went up the mountain/ And some of ‘em went down to the ground/ Some of their names are written in flames/ And some of them have just left town… It is possible that ‘carpenters’ wives’ may have been removed to discourage those who placed Biblical significance on the reference. Similarly ‘heading for another joint’ is more or less permanently replaced by …tryin’ to get out of the joint… further identifying the protagonist as a ne’er-do-well who is living close to the edge of legality. The lyrics now take on a tone of weariness. The narrator is still ‘keeping on keeping on’ but only because now it seems that he has no choice.

Tangled Love

Tangled Up in Blue has often been described as a love song. But it contains little of the lovelorn anguish of such songs as You’re a Big Girl Now and If You See Her Say Hello. The narrator’s apparent pursuit of the woman (or women) in the song is really a way of continually repositioning himself. By announcing that he is ‘still on the road’ he uses the title of Kerouac’s seminal work to announce to the world that ‘Dylan the countercultural poet’ has returned to replace ‘Dylan the family man’ of recent albums. But the protagonist of the song, who on one level is Bob Dylan, is not necessarily a sympathetic figure. Like Dean Moriarty he is obsessed by women and sex but there is a sense in which he himself has accepted his own imperfections. All he can do at the end of the song is proffer his thumb to the highways of America, and hope for the best. Through the different versions Dylan continues to renew what the song means to him at particular times in his life. Tangled thus becomes a kind of signature song symbolising Dylan’s dedication to touring. It presents a narrative which he can include elements of his own real life and feelings. As the words in the song change and evolve it becomes a kind of ‘self portrait’ which is, in the most quintessentially Dylanesque way, filtered through distortions of narrative, time and space. In the song Dylan sums up the position of all the ‘60s survivors’ like himself. Like John Lennon in the monumental God (1971) (which contains the highly provocative line …I don’t believe in Zimmerman…) he has renounced his idealistic beliefs and has embraced a new, if less comfortable, version of reality. But while Lennon declares sadly that …the dream is over… Dylan just grits his teeth determinedly and goes back on the road – where, of course, you can still find him….

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply