Although Bob Dylan made his name primarily as a writer of ‘protest’ songs, a number of the ‘love songs’ he wrote in his early ‘acoustic’ phase have become established standards. What makes these songs so memorable is their emotional realism. They have been covered by literally hundreds of male and female artists in a very wide range of different styles. The songs skilfully combine sophisticated poetic techniques with colloquial language and usually feature disillusioned narrators who are bidding farewell to relationships with a certain philosophical grace. The dominant tropes of the sentimental tradition which had dominated popular song up until the 1960s are subverted or rejected. There are no professions of undying devotion. Realising that their relationships are over, they roll up their sleeping bags and ‘hit the road’.

Dylan’s approach to these songs provided templates for the singer songwriters who emerged in his wake for their approaches to the subject of love. He took his cue from the fatalism and emotional realism of country music, combining this with the existentialist world view expressed in the work of the Beat Poets. Rather than idealising his lovers or pretending that their love will ‘last forever’, he appears to be analysing the relationships as abstract concepts, casting his (often unreliable) narrators in songs that could be called ‘little dramas’.

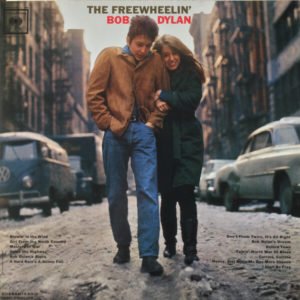

Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright, which appears on Dylan’s second album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), is an address to a lover which appears on the surface to be a ‘kiss off’ song. The narrator seems at first to be addressing the rejected lover in a slightly callous way …It ain’t no use to sit and wonder why babe… he tells her …if you don’t know by now… In other words he appears to be suggesting that she has been blind to the problems in the relationship. This is of course a rather arrogant position to take. So already we may be questioning the narrator’s emotional honesty. Here, as in the next two verses, the first line is repeated for emphasis, as if he is challenging her. This technique is drawn from the blues. The second line in the original recording ends with …It’ll never do somehow… which sounds particularly sarcastic. In later live performances (and in the ‘official’ lyrics this becomes …It don’t matter anyhow…) Despite the apparent bitterness of tone, perhaps this is a sign that the narrator’s apparent nonchalance is merely a front. Then Dylan presents us with a wonderful collocation of imagery: …When your rooster crows at the break of dawn/ Look out your window and I’ll be gone… The rooster is often used as a sexual symbol of male potency (as in such songs as Howlin’ Wolf’s Little Red Rooster) but here Dylan turns this on its head by suggesting that the rooster ‘belongs’ to the girl. Perhaps he is suggesting that she has somehow tried to control him. Or it could be that he has already left her in the night and is rather heartlessly telling her to wake up and find him gone. The use of pararhyme here (dawn/gone) which Dylan converts into a rhyme by exaggerating his Midwestern accent, suggests that what is being said somehow does not ‘chime’. Indeed, the narrator appears to be deliberately saying two things at once. Either he has already left her, or he is only threatening to do so. Both readings appear to fit.

The repeated line in the second verse …It ain’t no use in turnin’ on your light babe… again has two meanings. When the lover wakes up, it will do no good for her to switch on her bedside light. He will still be gone. There is also a suggestion that she has never really committed herself to him – her ‘light’ has never really been turned on, and now it is too late for her to do so. He tells us, in a delightful use of colloquial ungrammaticism, that this was …the light I never knowed… ‘Knowed’ rhymes rather awkwardly with: …I’m on the dark side of the road…. On the one hand this suggests that the narrator is somewhat naive or uneducated, although this in itself may be merely a sly form of manipulation. The image of the ‘dark side of the road’ may mean that that she cannot (and perhaps never has) see him for who he really is. It also suggests that he is depressed and miserable and quite possibly angry with her. But then he lets down his emotional defences: …I wish there was somethin’ you would do or say… he admits …to try and make me change my mind and stay… Now, it seems, he is being more honest with her, revealing perhaps that the attitude he has been displaying so far is merely a front. But the line is another criticism, in that it seems to infer that she has been ‘holding herself back’ emotionally from him, refusing to ‘shine the light he never knowed’. This is quite brilliantly juxtaposed against the deadpan line …We never did too much talkin’ anyway… This may suggest that their relationship was purely sexual and lacked emotional depth. Or it may imply that they never really confronted the problems in their relationship. With the repetition of the title line, the narrator again infers that he is placing no blame upon her. It is almost as if he is suggesting that the relationship is somehow independent of both of them – thus, they are just ‘not meant’ to be together. Yet given his apparently cynical attitude, it is hard to know whether he is being sincere or not. It is quite possible that the narrator does not even know the answer to this himself. Dylan presents the song as a drama in which we only hear one speaker. But we can certainly imagine what her responses will be.

We still do not really know whether the narrator has left the girl or whether he is just contemplating doing so. We may perhaps picture him lying in bed with her as the dawn comes up, watching her sleep and turning over his emotional confusion in his mind. The song’s attractive, upbeat melody, derived from the rather jolly traditional song Who’s Gonna Buy Your Chickens When I’m Gone, combined with Dylan’s nonchalant tone, suggests that he will be quite happy to ‘move on’. The use of colloquially shortened words: turnin’, somethin’, callin’, sayin’ suggests that the narrator is taking this all rather lightly. In the line …I’m thinkin’ and a-wonderin’, walkin’ down the road… he uses no less than three of these, piling on the impression that he is carefree. But this is followed by the song’s ‘killer lines’ …I once loved a woman, a child I’m told/ I gave her my heart but she wanted my soul… The first line appears to be something of a ‘put down’ as he ‘infantilises’ her. The second line is one of Dylan’s most memorable poetic expressions, couched in simple language but wonderfully ambiguous. It expresses a potent male fear that a woman may be trying to take him over and control him. Perhaps normally we might sympathise with this. But in the context of this song, with its many sly put downs, it also suggests that the narrator is giving us a rather weak excuse for why he himself is not prepared to make the relationship work. By claiming to be a ‘victim’ he appears to be dodging responsibility. Or maybe the woman really is over-controlling. This is followed by the title line, again suggesting the kind of emotional exhaustion which can kill a relationship. From a male point of view, this expresses the fear that many men have of being emotionally smothered by women. From a female perspective, this may be just a pathetic excuse for his lack of commitment to her. Perhaps it is him, rather than her, who is actually at fault for all of this. The song can be, and often has been, sung by women, including Joan Baez and many others. With a little switching of pronouns, it can make perfect sense the other way round. Thus Dylan has, in a few suggestive words, identified a universal dilemma which lovers face. How much of ‘themselves’ are they prepared to sacrifice in a relationship? When will that sacrifice become too much to bear? This is a song written by a twenty one year old, but his innate understanding of the dynamics of relationships is quite uncanny.

After this, the last verse, in which the narrator finally bades farewell to his lover, is something of an anti-climax, although the lines …Goodbye’s too good a word, babe/ So I’ll just say ‘fare thee well’… play with language in a teasingly ambiguous way. He is clearly still in love with her but tries his best to reassure us that he respects her and wishes her well. But perhaps he is being slyly sarcastic again. The playfully oxymoronic ‘Goodbye’s too good’ may be another put down. Or it may suggest that he if he leaves her, this will not be ‘for good’. Dylan’s greatness as a ‘sound poet’ is clearly on display here. He creates a song which he himself, or anyone covering the song, can sing in different ways. The song ends with another apparent display of casual dispassion: …I ain’t sayin’ you treated me unkind/ You coulda done better but I don’t mind… The narrator seems to be wriggling on a pin here. It’s now really hard to believe that he ‘doesn’t mind’. And when he follows this with …You just kinda wasted my precious time… he surely reveals himself as an unreliable narrator. All through the song he has apparently tried to treat his lover with respect but now he descends into recrimination, coming over as being merely arrogant. Is ‘his’ time more ‘precious’ than hers? In reality it is he who is being ‘precious’ – a spoilt brat, perhaps. She is, it seems, well rid of him.

In Don’t Think Twice Dylan thus creates a character who embodies many of the negative sides of maleness. Johnny Cash, having covered the song in a rather upbeat version, called it a ‘great country song’. And he, of course, should know. It certainly contains many of the characteristics that make country music unique. The narrator’s faults or weaknesses are openly displayed, as in the many ‘prison songs’, such as Merle Haggard’s Mama Tried – in which the narrator regrets his past crimes – or Lost Highway, written by Leon Payne and memorably recorded by Hank Williams, in which the singer looks back with mortification on his ‘life of sin’. In some ways, though, Don’t Think Twice is closer to songs such as Johnny Cash’s I Walk the Line, in which the narrator’s declarations of loyalty to his lover seem so exaggerated that it seems that he is willing not only us but himself to believe them, or Tammy Wynette’s Stand by Your Man, whose supposedly ‘anti-feminist’ sentiments and avowals of her support for her husband actually suggest great insecurity. Yet Dylan’s song is more psychologically complex, and even more open to interpretation, than either of these two classic ‘confessionals’.

One Too Many Mornings, which appears on The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964) is another ‘anti-sentimental’ song which is influenced by country music, especially in terms of its imagery and emotional realism. Again the tone is conversational and regretful, but here the emotions are clearly expressed without ambiguity. The relationship being referred to is over, which is a cause of great sadness to the narrator. The song is, at least in its original version, quiet and reflective. Dylan begins by painting a picture of a scene in stark language. He makes very effective use of alliteration, with a proliferation of ‘d’, ‘m’ and ‘s’ sounds: …Down the street the dogs are barkin’/ And the day is getting dark/ As the night comes in a-fallin’/ The dogs will lose their bark… ‘Day’ and ‘night’ here function as metaphors for the narrator’s emotional state. …The silent night will shatter from the sounds inside my mind… is perhaps a little overstated, but shifts the focus from the external to the internal. The repeated refrain …I’m one too many mornings and a thousand miles behind… neatly conflates time and space, strongly suggesting that the narrator, and his relationship, are ‘washed up’ …From the crossroads of my doorstep, my eyes they start to fade… is another slightly awkward line, but the song itself is about feeling awkward. The narrator looks back for one last time at the room where …my love and I have laid… The triple alliteration in ...I gaze back to the street, the sidewalk and the sign… sounds soothing and comforting. The final statement that …You’re right from your side and I’m right from mine… is straightforward. The song itself is less equivocal than Don’t Think Twice in its portrayal of a doomed relationship. Yet it is a song whose meaning Dylan has been able to play with considerably in performance. A passionately ‘electrified’ version of the song is played on the legendary 1966 tour, preceded by Dylan’s pronouncement that …it used to go like this… Now it goes like THIS…. Later, in an informal 1969 session with Johnny Cash, the duo really make the song ‘swing’. It becomes an optimistic singalong celebrating individual freedom. …You’re right from your side, Bob/ And I’m right from mine… Johnny sings.

Another ‘crossroads’ is faced in Mama You Been on My Mind (1964), one of the many songs from this extremely prolific period which did not make it onto an album. Here Dylan displays an acutely economical poetic sensibility. The song begins: … Perhaps it’s the colour of the sun cut flat/ An’ covering the crossroads I’m standing at… or maybe it’s the weather or something like that…. Here the internal contrast in the sound of the words… the alliteration of ‘c’s’ – ‘colour’, ‘cut’, ‘crossroads’ and ‘s’s’: “it’s”, ‘sun’, ‘standing’…. suggest an inherent contradiction in what the narrator is feeling. Then there are the line endings: ‘at’, ‘flat’, ‘that’, all supposedly suggesting a kind of finality with regard to how he is thinking about the relationship. But these endings are so pointed, so abrupt, that we may wonder if the narrator is merely fooling himself about this failed relationship. Then there is the extraordinary image (and sound) of ‘the sun cut flat’, as if the scene being described is somehow two dimensional: like the sun having been ‘cut out’ in a very young child’s picture book. But this is the ‘colour’ of the ‘flat sun’…. Maybe the sun is shaded by clouds, or perhaps this is a sunset. But the sun, which is somehow skewed or unnaturally shaped, somehow ‘covers’ the clearly metaphorical ‘crossroads’ that the singer has reached in his life. Coupled with the words ‘perhaps’ and ‘maybe’, all this suggests an overwhelming feeling of uncertainty. It is as if the singer does not know what day it is, or where his ‘crossroads’ is actually located. As he admits in the next verse …My mind is hazy and my thoughts they might be narrow…. Later on, in the most heartbreaking line he states …it don’t even matter who you’re waking with tomorrow… (in an alternate version… where you’re waking up tomorrow…). But all of this is, of course, a bluff. In reality the narrator is devastated by the loss of the loved one, but his attempt to retain his dignity and move on and the fact that he even bravely tries to confront the image of her ‘waking up’ (presumably naked in bed) with another lover is what makes the song so affecting. In a way the whole message is contained in the first two lines. Neither the singer nor the listener knows what the ‘colour of the sun cut flat’ is. Sound and image are united to invite the listener into this powerful exposition of mental confusion. The singer stands at the crossroads, but is blinded by this ‘flat sun’ and has no idea which road to take.

A handful of Dylan’s early songs express pure romantic feelings, although Dylan is always careful to avoid sentimentality. The wistful ballad Girl from the North Country is a moving evocation of the power of memory, which throws in a few highly evocative turns of phrase such as: …When the wind hits heavy on the borderline… and the politely restrained and respectful: ..It curls and falls all down her breast… as the narrator fondly recalls his first love back in the ‘North Country’ of Minnesota. Boots of Spanish Leather is a pained appeal to as lover who has deserted him to go abroad. Both songs use variants of the melody of the traditional Scarborough Fair. Tomorrow Is A Long Time (first performed in 1963), uses simple pastoral imagery to convey the singer’s yearning for his lost love. Here the narrator is as love struck and tearful as many a crooner. …There’s beauty in the silver, singin’ river… he sings …There’s beauty in the sunrise in the sky/ But none of these and nothing else can touch the beauty/ That I remember in my true love’s eyes… This was another song which failed to make it onto a Dylan studio album, although it was sensitively rendered in a heartfelt 1966 version by Elvis Presley, who treats it as a straightforward country ballad with simple guitar accompaniment. It was later covered by many other artists, including Rod Stewart and Sandy Denny. In some ways it became Dylan’s first ‘romantic standard’. On hearing Elvis’ version, Dylan – having been besotted by ‘The King’ as a teenager – proudly declared that it was the one cover of his songs that he treasured the most. But he rarely performed the song in his early days, stating that he felt awkward about singing such a purely romantic number. Such discomfort indicates that at this point he still seemed to reject any kind of ‘sentimentality’. He was on the point of plunging into his most experimental and revolutionary period. His 1965-66 albums Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde featured many long and highly imagistic songs and projected a view of relationships which was generally detached and ‘cool’. The women in these songs tend to be shifting, elusive, symbolic figures like the mesmeric Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands, the indefinably ‘ghostly’ Johanna in Visions of Johanna, or the tragically (or sometimes comically) deluded subjects of Like a Rolling Stone, Just like a Woman or Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat. Even when he makes a direct address to a lover, as in the joyous I Want You or the Zen riddle Love Minus Zero/No Limit, the objects of the song tend to be praised mostly for their intelligence, their guile or their emotional equanimity. There is no moonlight in these songs, and certainly no roses.

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply