A new ‘stand alone’ single by Bob Dylan has always been a rare thing. In June 1971 Watching the River Flow arrived in our house – a little, unfancy artefact with that distinctive orange label. It was not a big hit, or any kind of hit at all. Nor was it any kind of lyrical masterpiece. But the music was pretty stirring, with some nice piano licks from producer Leon Russell. The song basically reiterated much of what we had heard on 1970’s New Morning – Dylan was enjoying his ‘laid back’ country retreat from the limelight. Although he told us rather wistfully that he wished he …was back in the city, instead of this old bank of sand… it was a little hard to believe him. He sounded content with his lot. A pleasant diversion, then, but not really what we loved Bob Dylan for. After many plays, it was time to flip the record over. At first sight it was disappointing that this was not another new Dylan song. But we had never heard anything quite like this. The ‘B’ Side featured a stunning, heart-wrenching version of a song then labelled as ‘traditional’. It showcased Bob’s eccentric but always memorable piano playing. Despite it being a ‘cover’, in many ways it was his most intimate recording ever. Both the songs on the single present a message of reticence. The singer in Watching the River Flow is quite content to sit and let nature take its course. But the pained, regretful narrator of Spanish is the Loving Tongue is prevented from achieving his aim of being reunited with his lover by the bounds of geography and prejudice. You can tell that this causes him terrible pain. He accepts his fate but, try as he might, he cannot rid himself of the image of his lover. Something is calling him back to action but he is still strangely paralysed, by fortune and circumstance.

If any one song illustrates the way in which Bob Dylan can twist a lyric into different shapes and convey varying emotions in different performances it is Spanish Is the Loving Tongue, which he produced a series of different versions of between 1967 and 1976. The performances – most of which have now been released – graphically illustrate Dylan’s musical virtuosity. Even attempts at the song recorded at the same sessions are quite radically different from each other. What they illustrate most of all is Dylan’s greatness as a singer. In the early years of his career, up to the motorcycle crash of 1966, we knew what to expect from him in that department. He was acclaimed as poet, prophet and seer and the ‘voice of his generation’. The brilliant, poetic lyrics would be delivered in a nasal snarl that insisted that we listen to the words. You could never play these records as ‘background music’. Yet here, although he is giving us an old cowboy ballad of thwarted romance, through the sheer power of his vocal dexterity he produces a performance that is as affecting in its own way as Like a Rolling Stone or Positively 4th Street. Here he is utterly focused on the feelings of angst that he draws out of the song.

Dylan’s eccentric piano style provides a complement to his singing throughout, as if it is another ‘voice’ – perhaps that of his estranged lover – as he stabs at the keys in a rather disjointed way. The opening lines set the scene: …Spanish is the loving tongue/ Soft as music, light as spray/ ‘Twas a girl I learned it from/ Living down Sonora way… Dylan’s voice begins fairly smoothly – not quite in a Nashville Skyline croon but with the slight edge he added for New Morning, at the sessions for which the song had been recorded in June 1970. Then he teases his way around the next line, the gently self-deprecating …I don’t look much like a lover… But he is clearly haunted by her memory: …I hear her love words over… Then his voice rises to give emphasis to …Mostly when I’m all alone… in a way that conveys a stoical resistance to internal pain. He stretches out the final line at the end of the verse …Mi amor, mi corazon… (‘My love, my heart’) sounding infinitely sad.

His fingers run up and down the keyboard for just a couple of seconds, as if plunging into some emotional depths and then re-emerging bravely to engage with memories of the girl. We hear that his dusky lover listens to the sound of his spurs on his horse as he was riding towards her and then – in what are perhaps the song’s most engaging lines – that she would …Throw that big door open wide/ Raise those laughing eyes of hers… Dylan stretches out the final syllables of each line for emphasis. This is the moment in the song when the singer really reveals why he is so gloomy. But this is now a truly life affirming moment, in which we stand with him by that ‘big door’, anticipating her warm embrace. Then we jump from ecstasy to despair in two lines: …Oh how those hours would go a-flying/ All too soon I would hear her sighing… Dylan’s voice rises and falls but he never sounds maudlin or overdoes the emotion. There is a short piano passage before the final verse, in which the narrator reveals that he can no longer ‘cross the line’ (the US-Mexican border) to visit her due to his involvement in a ‘gambling fight’. It seems, however, that a cultural divide is also keeping them apart. The most affecting line in the final verse comes when Dylan takes a deep breath and delivers …Still I’ve always kind of missed her… a truly magnificent piece of understatement. It is as if he has literally had to squeeze the words out. As the song ends abruptly we are left with two broken hearts. Dylan pours his heart and soul into every moment. It appears that, despite apparently enjoying the ‘New Morning’ of his rural domestic retreat, he is not really just content to ‘watch the river flow’. Something is nagging away at him – a feeling that will only be satisfied when he gathers the courage to ‘cross the line’ again in order to realise his true artistic potential.

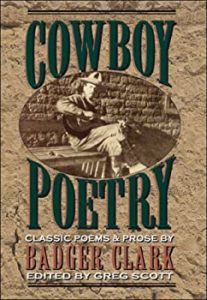

Spanish is the Loving Tongue is a ‘folk standard’ which has been recorded by many artists. Although often labelled as ‘traditional’ its lyrics were actually first published as a poem called A Border Affair in 1907 by Charles Badger Clark, the ‘cowboy poet of Wyoming’, and were set to music in 1925 by composer Billy Simon. A version by cowboy singer Tex Fletcher called Border Affair was recorded in 1936. The pianist Richard Dyer-Bennett, who performed folk material in a near-classical style, popularised the song in the 1950s. Pete Seeger recorded it on his album Rainbow Quest in 1960. Other notable versions include those of Ian and Sylvia, Tom Paxton, Liam Clancy, Tom Waits, Just Collins, Marianne Faithfull and Emmylou Harris. The female singers all reverse the pronouns to convey the song from the woman’s point of view. It is perhaps surprising that the song has never been performed by Joan Baez. One might even speculate that Dylan may have been thinking of his doomed affair with Baez when he recorded the sparse 1970 version. Baez’s family is of Mexican origin and Dylan’s performance certainly conveys the confusion of their much-feted relationship.

It is clear that Spanish Is the Loving Tongue is a song which Dylan has had particular affection for. His first version was recorded in the basement of Big Pink in 1967, accompanied by the Band, with Rick Danko prominent on bass and Garth Hudson on organ. Dylan’s vocal here is surprisingly deep and sonorous, anticipating the voice he would use on Nashville Skyline and New Morning. It is thus not surprising that he attempted seven takes of the song in the first sessions for Self Portrait in April of 1969. One of these takes appeared on the notorious album simply called Dylan (sometimes known as the ‘blackmail’ album), a collection of outtakes from the Self Portrait and New Morning sessions which CBS released without Dylan’s consent in 1973 after he temporarily left the label to record Planet Waves for Asylum Records. This recording, like several others on the collection, was overdubbed with female backing vocals by Hilda Harris, Albertine Robinson and Maeretha Stewart. At the time of release it was rumoured that this had been done without Dylan’s permission, although in fact much of the Self Portrait album was similarly overdubbed. At the time of release, this recording – which replaces verse two with some ‘la la la’s – and which is heavily stylised, with Dylan indulging in a deep crooning style, was hated by many Dylan fans who saw it as him ‘bowing to commercialism’. The contrast to the previously released ‘B’ side is certainly striking. However, given the diversity of Dylan’s output in succeeding decades and his embrace of ‘crooning’ styles in his twenty first century work, this version makes considerably more sense today than it did when originally released.

Two other versions which were recorded around the time of the New Morning sessions have recently seen the light of day. These are much more in line with what we would expect from Dylan but it is striking how much they differ from the ‘B’ side recording. The track which appears on the recently released ‘50th Anniversary’ collection has some muted guitar accompaniment and features vocals that veer slightly more towards the ‘crooning’ style of the Dylan version. Another take appears on the Bootleg Series release Another Self Portrait. This is a piano solo but features an almost spoken vocal in places. These three versions, which can all be counted as classic Dylan performances, eloquently demonstrate his attitude to recording. They are all ‘live in the studio’ performances. Each one tries to convey the song in a different way. There is no sense in these recordings that Dylan is striving towards a definitive take. Each one expresses a slightly different mood and range of emotions.

Dylan’s version from the 1974 Blood on the Tracks sessions (now released on the Bootleg Series box set More Blood, More Tracks) comes from the earlier ‘New York’ recordings and features Dylan on guitar, Tony Brown on bass and Paul Griffin on piano. It includes some rewritten lyrics, presumably composed by Dylan himself: …How my heart could not stop beatin’/ When I heard her tender greetin’… and later …We said a swift goodbye on that dark windy night… Dylan has ‘claimed’ Spanish as his own now. Certainly its subject matter fits with that of this suite of songs of romantic despair and anguish. He uses these lyrics again on the 1975 rehearsal which appears on the Rolling Thunder box set released to coincide with Martin Scorsese’s film The Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story in 2019 and in the sole live version he performed on the tour, opening the show at San Antonio Texas in 1976 with a solo guitar and harmonica.

The alternate versions of Spanish Is the Loving Tongue can be seen as a series of ‘bridges’ between the different styles Dylan was experimenting with during this decade. The performances of the song by other artists (almost all of which can be found on youtube) present a tragic ballad with some beautiful lyrical passages and much poignant romantic yearning. But Dylan does much more with the song. He personalises it, using it as an expression of the varying emotions he is feeling during a decade in which his own romantic life was particularly turbulent and in which he was working through a number of different musical styles. Tucked away on that obscure ‘B’ side from 1971 is one of his most inspired and committed vocal performances in which, for a few intense minutes, we ride with this cowboy across an uncertain borderland, knowing that we can never return to the love and joy we experienced in the past. If there is one track you might want to play to your friends who still, after all these years, go for the line that Dylan may be a great lyricist but that he ‘can’t sing’ – this is it. There is lust here, there is tragedy, there is despair… but buried underneath all this, we can the singer expressing the hope that one day he will mount that steed and ride off across that border again. As the momentous performance ends, all we can do is sit quietly and listen to the sounds of the night. Soon, surely, we will hear the click of his spurs…

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply